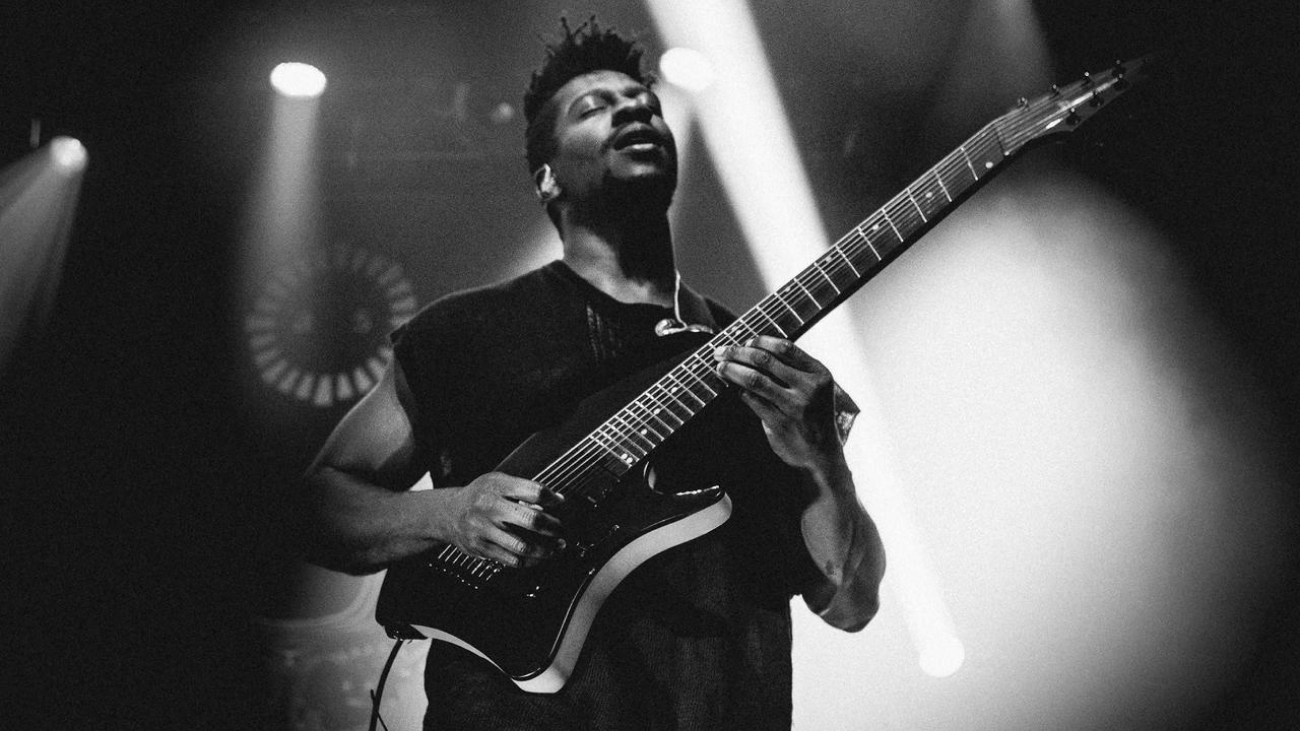

Now that you know what to look for when you purchase a metronome (Part 1), let’s get started with actually practicing with one. A lot of this may be review for more advanced players, but you may want to skim through and see if there any rusty spots in your playing or knowledge.

When you’re getting set up you’ll want to practice with a pick, and if you’re playing amplified, it’s better to practice clean before adding distortion so you can work on playing with clarity and precision that distortion can cover up.

Old Joke: How do you send a guitarist running for the hills? Put a page of sheet music in front of them! It’s true that most guitarists cringe at the thought of reading music, but if you have any aspirations of being a professional guitarist, you will eventually have to face this inevitable evil. The most important part of reading music, even more important than knowing the pitch names and locations, is their rhythmic value or duration.

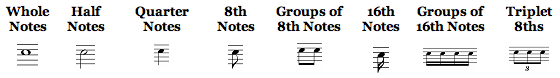

The basic notational values on a staff are:

You’ll find that the metronomic break down of music is nothing more than basic mathematics. A whole note is equal to two half notes. A half note is equal to two quarter notes, (therefore a whole note is equal to four quarter notes.) Two 8th notes fit into a quarter note, (4 into a half, and 8 into a whole.) Two 16th notes fit into an 8th note (4 per quarter, 8 per half, and 16 per whole), etc…

You’ll end up contextually understanding the way these work by continuing through the examples below:

A) Understanding your time signatures.

Music is divided up into measures or bars the same way a day is divided into hours. Measures are essentially groupings of beats into regular intervals. A time signature or meter signature shows how measures are divided up into beats (like an hour is divided into minutes) and the duration or note value of a single beat. This flow chart explains the hierarchy of a piece of music from largest (lengthiest) value to the shortest value.

Song -> Section (groupings of measures) -> Single Measure -> Beat -> Subdivision of the Beat

Time signatures are usually represented by two numbers that look like a fraction. This is how a few popular time signatures are represented on a staff:

![]()

The bottom number represents the type of note that gets the beat. For example a 4 represents a quarter note, a 2 represents a half note, and an 8 represents an 8th note and so on. Now even though they may be called a quarter, half, and 8th note does not necessarily mean that there are 4, 2, and 8 respectively in a measure. That number of beats in a measure is represented by the top number of the fraction.

For example in 4/4 the measures are divided into four quarters as the regular beat. In 3/4 the measures are divided into three quarter notes as the beat. In 6/8 there are six 8th note beats per measure. Now this does not mean that these are the only types of notes you can use, just the regular division of the measure. Quarter notes can be divided into 8th notes or 16ths, or extended into half notes or whole notes and so on as mentioned above.

There are three broad types of time signatures. Simple time signatures are groups of beats that can be divided into two equal notes. The top number of the time signature expresses such times as 4/4, 3/4, 2/2 etc. Compound time signatures are groups of beats divided into three equal groups such as 6/8, 9/8 or 12/8. Complex, or odd time signatures can not be divided into equal intervals such as 5/4, 7/8 etc.

![]() If you see a larger letter C in place of a time signature, all it means is a shorthand method of specifying common time, or 4/4. A C with a slash through it represents cut time, or 2/2.

If you see a larger letter C in place of a time signature, all it means is a shorthand method of specifying common time, or 4/4. A C with a slash through it represents cut time, or 2/2.

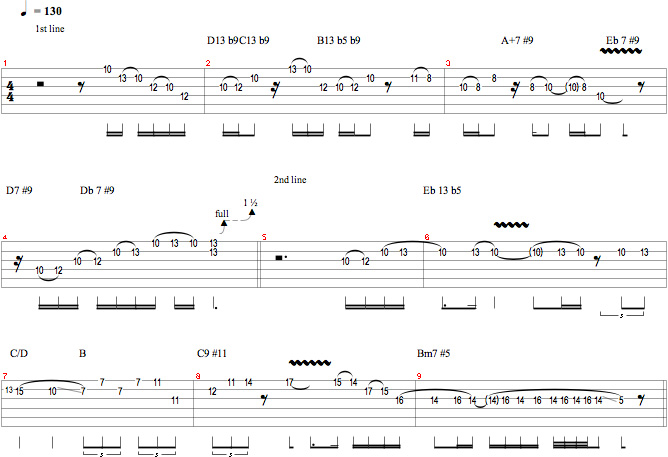

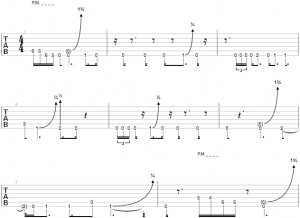

B) Practicing your Rhythmic Subdivisions

Let’s practice with a simple example. Turn your metronome on; set the time signature to 4/4 and the tempo to 80 bpm. In later installments we will work with other time signatures, but its best right now to get used to the most common time signature in music. You will hear the click popping at a regular interval and possibly a special click on the first beat of the group of four. This is how a 4/4 quarter note rhythm is viewed on the staff.

![]()

The makeup of a staff is a lot simpler than it appears. The five lines represent the order of pitches from low to high (top to bottom.) On the far left you’ll see the treble clef, which is simply a glorified G, because it circles the second line from the bottom which is the note G. The purpose of a clef is basically to specify the arrangements of notes on the staff, because there are other clefs designed for other instruments with different sound arrangements. Pianos, Guitars, Violins and many others use treble clefs while Basses, Cellos, and others use a Bass Clef. There are many other types of clef, but all you need to worry about right now is the treble clef.

To the right of the clef is the time signature as mentioned above. Many times you will see a key signature or a series of sharp signs (#) and/or flat signs (b) that specify the key of the piece between the clef and the time signature. Don’t worry about what that means right now, since we will be using a blank key signature which can either specify an open key signature or more commonly, the key of C, which has no sharps or flats. After the time signature should usually be the notes themselves.

![]() They will have two main orientations. All notes that are below the central line will have their “stem,” or the line that branches off the circle or note head, pointing upwards. All notes above or on the middle will usually have their stems pointing downwards.

They will have two main orientations. All notes that are below the central line will have their “stem,” or the line that branches off the circle or note head, pointing upwards. All notes above or on the middle will usually have their stems pointing downwards.

Now pick a random note or chord, it doesn’t have to be the note C represented below, and play along with the click of the metronome. Count along out loud as the metronome clicks. Click play below to hear the examples:

Ex.1:

Let’s subdivide these quarter notes into 8th notes. Basically we will be playing an extra note between the clicks of the metronome. Continue to count with the clicks.

Ex.2:

![]()

Now let’s count with the 8th notes by saying the word ‘and’ on the offbeat, or on the note in between the beat. The word ‘and’ is expressed by a + sign.

Ex.3:

![]()

We’ll now divide the 8th notes into four groups of 16th notes, essentially having three notes on the off beat. We ’ll count these three notes as ‘e’ ‘+’ ‘a’.

Ex.4:

![]()

You may notice this getting a bit harder to play consistently. If you are finding this tempo to be too difficult to play, slow it down to maybe 60bpm or slower. Remember clarity is the most important thing here. If the notes are feeling rushed or forced then something is wrong and you need to slow it down until you feel (see above) the rhythms. You’ll also want to be alternate picking – picking both up and down using only small flicks of your wrist. There is a great lesson on alternate picking located HERE.

At any moment you should also be able to turn off the metronome and continue to feel the regular beat in your mind. This is your ultimate goal of practicing with a metronome. If possible (like with a foot pedal on/off switch) try playing a bar with the metronome on and then again with the metronome off and continue on/off.

At any point you may want to choose a different note to mix things up.

In this next example we will be changing the subdivisions every measure to practice switching between the feels of steady quarter notes, 8th notes, and sixteenth notes.

Ex.5:

Now let’s take things a step further and change the subdivisions of notes in the measures themselves. This may be harder for you; remember to set your metronome to a speed where you can play the examples cleanly.

Ex.6:

Two more very important note values that should be mentioned are half notes and whole notes. Remember, a whole note takes up a whole measure, or four clicks, and half notes take up two clicks with two notes per measure. Try the next two examples:

Ex.7:

Ex.8:

![]()

Finally let’s take a look at one last subdivision of the beat in 4/4: Triplet 8ths.

A triplet is a group of notes that are bound together so that they fit under the duration of only two of the notes by cutting off a small portion of each note. For example Triplet 8ths fit three 8th notes under the duration of two 8th notes.

Ex.9:

![]()

Try mixing in the triplets with the other groupings of the notes until you feel comfortable switching between separate rhythms while using the metronome. When you feel ready, move on to the next example.

Don’t underestimate these examples. Moving from a triplet feel to a ‘straight 8th’ feel can be very difficult and require a lot of practice.

Ex. 10:

Now that you’re comfortable with mixed rhythms in a 4/4, continue to practice with the examples while speeding up the metronome. Remember precision and clarity is more important than going fast and hitting less notes. Try making up your own patterns and remember to feel the beat over relying on a metronome or drum kit. If you feel ready, make up your own finger patterns with varying notes and play them with these rhythms.

In the next installment we will begin switching between notes and playing various finger patterns while using more mixed rhythms. Also still to come are 32nd notes, triplet quarter notes (which are harder than they sound,) sextuplets, dotted notes, and many more rhythmic groupings.