Welcome back, fellow metallers! Last lesson, I introduced some basic rhythmic subdivisions and the palm muting technique. Expanding on palm muting and timing importance, this lesson will examine some ways to go about creating original riffs with common chord diads, rhythmic embellishments, and knowing when and when not to palm mute.

Common Diads –

Perfect 5th, Perfect 4th, Major 3rd, Minor 3rd, Minor 6th

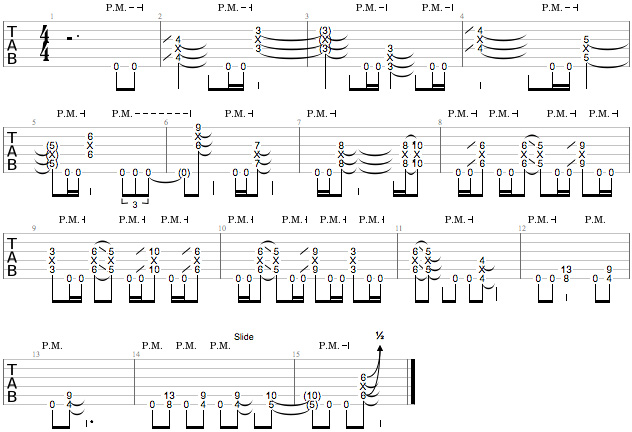

The following examples illustrate common chord diads based in the key of D. Two-note chords are great for adding tonal variation to your riffs. Diads are not full chords, but the intervals relative to the root note, in this case D, reflect major and minor chord qualities.

Perfect 5th Diad

A diad containing the root note and its 5th, also known as a power chord, is one of the most common chord shapes in metal and rock. Take notice of this shape, because it’s the foundation for building bar chords and will eventually become second nature to you.

A 5th position D5 chord is formed by placing your first finger on the 5th fret of the 5th string, and third finger on the 7th fret, 4th string. The root note is D and the 5th is A. Another cool thing about basic 5th diads is their ease in Drop D tuning (every string tuned to standard pitch, except the 6th string, which is dropped a full step). Striking the open 6th and 5th strings forms an open D5. Simple, huh?

Perfect 4th Diad

A perfect 4th diad contains the root note and the 4th above it. In 5th position, a 4th diad with bass note D is formed by barring the first finger over the 5th fret, 5th string D, and the 5th fret, 4rd string- which is G.

4th chords are great for adding variety and heaviness to riffs because they sound similar to perfect 5ths. The difference in voicing that having the 5th on the bottom rather than on the top creates can add variety when used between other diads. Just think of it as an inverted power chord.

Major 3rd Diad

The root note and the 3rd interval up in the major scale form a major 3rd diad. If you are already familiar with common open chords, you’ll notice the root note and 3rd interval shape is the same as the first two notes of the open C chord.

Continuing with our 5th position D, place your second finger on the 5th fret, 5th string, and your first finger on the 4th fret, 4th string. The root note is D and the major 3rd is F#.

Minor 3rd Diad

The minor 3rd diad is formed like the major 3rd diad, except the 3rd interval is a half step or one fret lower – the 3rd interval in the natural minor scale. Place your third finger on the 5th string D and your first finger on F, which is located on the 3rd fret of the 4th string.

Minor 6th Diad

A minor 6th diad can be viewed as raising the 5th interval up a half step. The best way to finger this diad is to place your first finger on the 5th string D, and your fourth finger on the 8th fret, 4th string, which is a Bb.

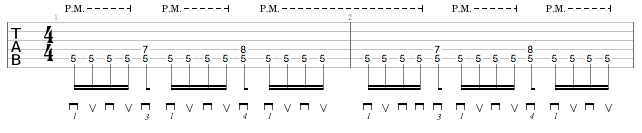

When and When Not to Palm Mute

As addressed in the previous lesson, palm muting is the cornerstone of metal riffs. In light of this, not palm muting juxtaposed with palm muting can create great variety in riffs, bring out melodic lines, and establish pedal tones. Most metal riffs are based around palm muting lower pedal tones and bringing out melody through unmuted notes.

The following examples illustrate some ways to combine the palm muting technique with unmuted notes using a mixture of diads. Go ahead and tune your sixth string down to D, as each of the following exercises is in Drop D.

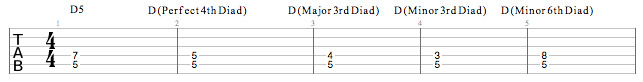

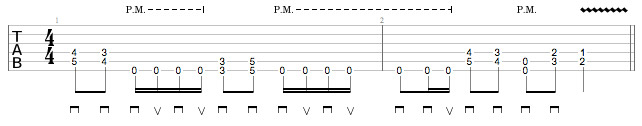

Figure 1

This example is reminiscent of classic thrash metal and contains a D note on the 5th string, 5th fret, and D5 and D minor 6th diads. The root note, D, is alternate picked and palm muted. The D5 and D minor 6th diads are not palm muted and hit with a strong down stroke. This will help practice palm muting the pedal tone and not palm muting chords and melodic lines. As addressed in my last lesson, practice these examples with a metronome and work to achieve a uniform tone with the alternate picked palm mute.

01 Figure 1 – Slow

02 Figure 1 – Fast

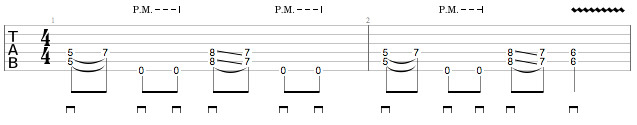

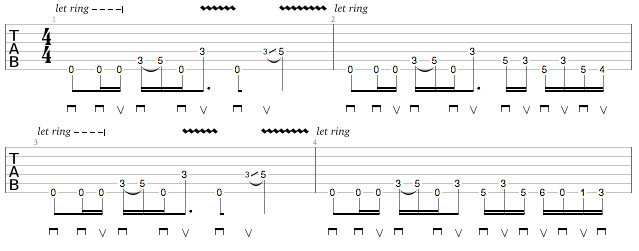

Figure 2

Figure 2 starts with a perfect 4th diad in D. The 4th interval is then hammered onto the 5th, forming a D5 power chord. Be sure to let the root note ring out as you hammer onto the 7th fret, 4th string with your third finger.

The low D on the 6th string is palm muted. Use your third and fourth fingers to form the 4th diads on the 8th and 7th frets in Measure 1, and 8th, 7th, and 6th frets in Measure 2. Chromatic chord shifts like this definitely add heaviness. Also, notice how the figure exclusively uses downstrokes for an added attack. The benefits of downstrokes are addressed in Lesson 1.

03 Figure 2 – Slow

04 Figure 2 – Fast

Figure 3

Figure 3 uses major 3rd diads and a palm muted pedal tone on the low open D. Barring your first finger over the 6th and 5th strings form the 5th diads. Also notice the gallop at the start of Measure 2. Simple rhythmic variance like this can spice up and add heaviness to your riffs.

05 Figure 3 – Slow

06 Figure 3 – Fast

Figure 4

This example shows a relatively simple melody with some alternate picking. Let the low open D ring out for a dirty and loose feel. This particular riff may be useful in a hard rock intro. This is the motif for the following riff, which expands on this melody. To give the riff more character, follow the slides and slight vibrato in Measures 1 and 3. I’ll expand on these concepts and other stylistic embellishments in the next lesson.

07 Figure 4

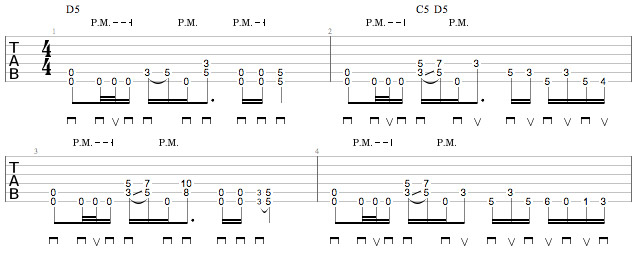

Figure 5

This riff expands on Figure 4 by adding a palm muted gallop in each measure and harmonizing many of the notes. You’ll notice that most chords are 5ths, save for one in Measure 1.

Notice the F note on the 3rd fret, fourth string from the previous example. To vary the riff, Measure 1 contains a minor 3rd diad, D being the root note and F being its minor 3rd. In Measure 3, notice the change to an F5 power chord on the 8th fret, 5th string. Dave Mustaine of Megadeth often uses this idea of introducing a chord as a minor or major diad, and then changing it to a 5th diad in a later measure for added intensity. Also, pay attention to the picking patterns and palm mutes.

08 Figure 5

Essential Listening:

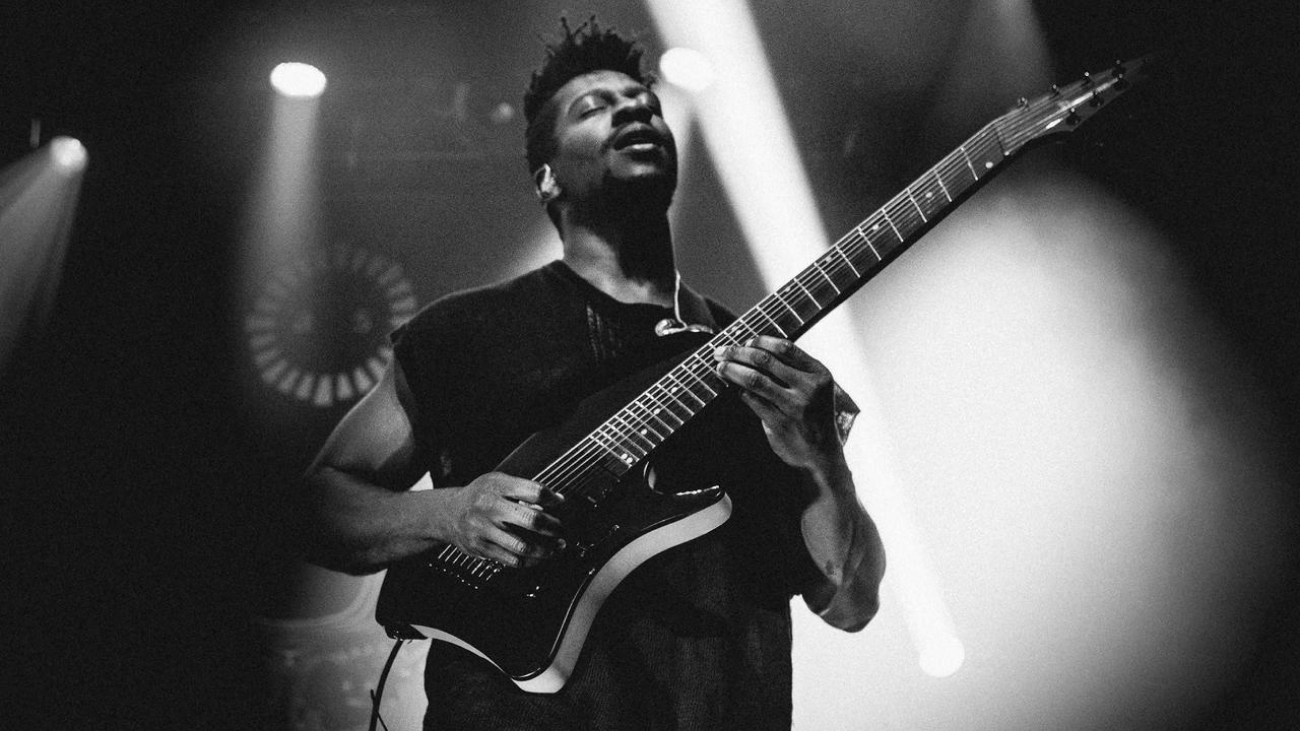

This lesson’s Essential Listening contains three crushing albums that are full of fantastic riffs. Mark Morton and Willie Adler from Lamb of God, Jerry Cantrell from Alice in Chains, and Dimebag Darrell from Pantera are all incredible riff writers, but notice how different their styles are. Listening to the greats and (eventually) learning their riffs can inspire your own riff composition and creative style.

Lamb of God – Ashes of the Wake, 2004

Lamb of God has come a long way in their career. Ashes of the Wake is their 2004 major label debut, and is a crushing arsenal of technical and dexterous riffs. Vocalist Randy Blythe screams like a demon, bassist John Campbell doubles each guitar riff note for note (!), and Chris Adler’s drumming takes advantage of rhythmic possibilities many bands overlook.

This album, exclusively in Drop D tuning, is all about precision and sounds very uniform and mechanical. But above all that, it’s extremely heavy. Highly recommended.

The riffs on Ashes are very fast, rhythmically diverse and exemplify the concept of varying between palm muted and unmuted notes. Take for instance, the main riffs in ‘Laid to Rest‘ and ‘Hourglass.’ Both songs contain riffs that pedal muted notes on the 6th string, while ringing out note sequences and in higher octaves.

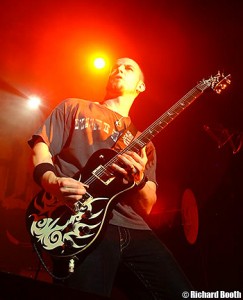

Alice in Chains – Dirt, 1992

This 1992 album is Alice in Chain’s most commercially successful record and features innovative guitar work from Jerry Cantrell. Although their first album, Facelift, has more of a classic metal influence than the grunge opus Dirt, the latter album is darker and heavier overall.

‘Them Bones‘ uses some chunky palm muted chromatic progressions and ‘Rain When I Die’ makes clever use of a wah pedal.

Alice in Chain’s style is more rock-based than the other two bands. Most of their riffs can be found in their verses, while distorted chords make up many of their melodic choruses.

Notice Cantrell’s looser and grittier approach to his rhythm parts – it goes to show that you don’t necessarily need to be a technical master to write sick riffs.

Pantera – Vulgar Display of Power, 1992

Pantera – Vulgar Display of Power, 1992

The late and great Dimebag Darrel bangs out countless classic riffs on Vulgar. From the simple and effective riff in ‘Walk‘ to the furious thrashing of ‘Rise,’ Dimebag incorporates — no pun intended — a grab bag of riff styling.

He can be fast and thrashy, and he can be loose and frantic. Dime also is a fan of incorporating varying diads into his playing, such as in the outro riff to ‘Mouth for War.’ If you’ve never checked out Pantera before, this is a great introductory album.

Notice also some of the similarities between Pantera and another Essential Listening band, Lamb Of God. Dimebag’s influence is easy to spot in the riffing of Morton and Adler, who take elements of his style into a fresh and extremely heavy direction.

Thanks for reading and good luck with your practicing! Take these examples along with the legendary riffs from the Essential Listening selections as starting points to develop your own riffs. Next lesson, I will explore more stylistic techniques, such as vibrato and slides, as well as how to avoid some common bad guitar habits. Stay tuned!