Introduction

In part 1 of the Stepping Out: A Guide To Playing Outside series, we looked at the use of side stepping (moving a motif, scale, or pattern up/down by a semitone) to instantly add dissonance and create tension within your playing. While this is an effective way of navigating the outside notes of your current tonality, it is not a very precise way of picking out notes or colors. It can also become predictable to the listener’s ears as they learn to hear these shifts.

In part 1 of the Stepping Out: A Guide To Playing Outside series, we looked at the use of side stepping (moving a motif, scale, or pattern up/down by a semitone) to instantly add dissonance and create tension within your playing. While this is an effective way of navigating the outside notes of your current tonality, it is not a very precise way of picking out notes or colors. It can also become predictable to the listener’s ears as they learn to hear these shifts.

This lesson will demonstrate how to be more subtle in your inclusion of outside notes and target specific intervals to give you a greater command over useable tensions in all scenarios. To do so, we will look at how utilising and imposing certain scales will produce idiosyncratic ideas.

The Tools

For the purpose of this lesson, we are going to talk about the use of 7-note palettes (scales). This is not exhaustive by any means, but 7-note palettes are the most commonly used and provide a practical platform for us to work from in later lessons, where we’ll cover other note palettes ranging from two to twelve notes long.

The reason I use the word ‘palette,’ as opposed to ‘scale,’ is because the word scale has become synonymous with the idea of practicing/rigidity/order/sequence. Thinking of your available notes as a palette promotes the idea that they are there to assist your creativity, and you should find unique ways to draw out colors from your palette. There are five common and usable 7-note palettes you can construct from the chromatic scale, each of which has seven modes for a total of 35 palettes. Listed below are the names of each, the intervals within them, and 4-interval harmonizations (tertiary).

Each of these palettes should first be practiced in the context of their respective harmonies to get used to the sound each produces. This should form part of your practice regimen and be exercised in the usual manner (cycle of fifths/fourths, positional, moving through the chord scale, arpeggios, etc. …)

Major Scale

| Name | Formula | Chord |

|---|---|---|

| Ionian | 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | Maj7 |

| Dorian | 1 2 b3 4 5 6 b7 | Min7 |

| Phrygian | 1 b2 b3 4 5 b6 b7 | Min 7 |

| Lydian | 1 2 3 #4 5 6 7 | Maj7 |

| Mixolydian | 1 2 3 4 5 6 b7 | Dom7 |

| Aeolian | 1 2 b3 4 5 b6 b7 | Min7 |

| Locrian | 1 b2 b3 4 b5 b6 b7 | Min7b5 |

Melodic Minor Scale

| Name | Formula | Chord |

|---|---|---|

| Melodic Minor | 1 2 b3 4 5 6 7 | Min(Maj7) |

| Dorian b2 | 1 b2 b3 4 5 6 b7 | Min7 |

| Lydian Augmented | 1 2 3 #4 #5 6 7 | Maj7#5 |

| Lydian Dominant | 1 2 3 #4 5 6 b7 | Dom7 |

| Mixolydian b6 | 1 2 3 4 5 b6 b7 | Dom7 |

| Locrian ♮2 | 1 2 b3 4 b5 b6 b7 | Min7b5 |

| Super Locrian* | 1 b2 b3 b4 b5 b6 b7 | Min7b5 |

*We often see this scale (Locrian b4) as Super Locrian or the Altered Scale. For our purposes here we will call it the Super Locrian due to naming issues for the following palettes.

Harmonic Minor Scale

| Name | Formula | Chord |

|---|---|---|

| Harmonic Minor | 1 2 b3 4 5 b6 7 | Min(Maj7) |

| Locrian ♮6 | 1 b2 b3 4 b5 6 b7 | Min7b5 |

| Ionian #5 | 1 2 3 4 #5 6 7 | Maj7#5 |

| Dorian #4 | 1 2 b3 #4 5 6 b7 | Min7 |

| Phrygian Dominant | 1 b2 3 4 5 b6 b7 | Dom7 |

| Lydian #2 | 1 #2 3 #4 5 6 7 | Maj7 |

| Super Locrian bb7 | 1 b2 b3 b4 b5 b6 bb7 | Dim7 |

Harmonic Major scale

| Name | Formula | Chord |

|---|---|---|

| Harmonic Major | 1 2 3 4 5 b6 7 | Maj7 |

| Dorian b5 | 1 2 b3 4 b5 6 b7 | Min7b5 |

| Phrygian b4 | 1 b2 b3 b4 5 b6 b7 | Min7 |

| Dorian #4 ♮7 | 1 2 b3 #4 5 6 7 | Min(Maj7) |

| Mixolydian b2 | 1 b2 3 4 5 6 b7 | Dom7 |

| Lydian Augmented #2 | 1 #2 3 #4 #5 6 7 | Maj7#5 |

| Locrian bb7 | 1 b2 b3 4 b5 b6 bb7 | Dim7 |

Double Harmonic Scale *

| Name | Formula | Chord |

|---|---|---|

| Double Harmonic | 1 b2 3 4 5 b6 7 | Maj7 |

| DH mode 2 | 1 #2 3 #4 5 #6 7 | Maj7 |

| DH mode 3 | 1 b2 b3 b4 5 b6 bb7 | Min Triad |

| DH mode 4 | 1 2 b3 #4 5 b6 7 | Min(Maj7) |

| DH mode 5 | 1 b2 3 4 b5 6 b7 | Dom7b5 |

| DH mode 6 | 1 #2 3 4 #5 6 7 | Maj7#5 |

| DH mode 7 | 1 b2 bb3 4 b5 b6 bb7 |

*As the intervals in the Double Harmonic modes are very altered from the Major Scale modes, it is easier to just number these. At this point, I would suggest taking some time to learn the Double Harmonic scale and its positions on the fretboard as it may be easier to think of the parent Double Harmonic for whichever mode you want to use. For example, to use mode three in A we would need to trace back three tones to F and play a double harmonic from there. That being said, we should be focusing on the intervals anyway, as opposed to the names or positions.

While you might recognise some of these scales under different names, these scales are named the way they are for a particular reason. Each parent scale (Major, Melodic Minor, Harmonic Minor, etc…) has an individual name for easy identification. The 7 modes within each parent scale have been referenced to the the modes of the Major Scale (i.e Dorian b2, Lydian #2, etc…) as most of us will be familiar with the construction of the seven Major Scale modes. This prevents you from worrying about the spelling of the Javanese scale, or the Hungarian Minor, or the Jabberwocky Pentamonochromatic, or the… (you get the point!) – creating a clean reference system for these palettes.

In order for your ear to draw on these sounds effectively, it is essential that they are internalized. This is particularly pertinent in our case, as to use these palettes for creating outside sounds, they must be superimposed over differing tonalities to create tension. Otherwise, they will still be respectively ‘inside.’ (i.e. a Phrygian Dominant over a 7b9 chord is inside.)

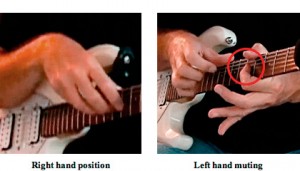

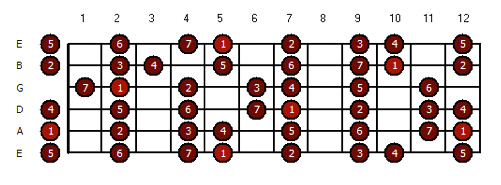

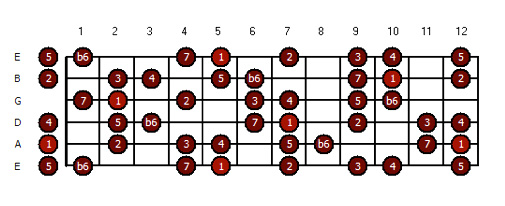

Within a lesson this size to drudge through every position of every parent scale listed (although useful) is outside of our scope. Even if you are unfamiliar with most of these scales, try to work out where each interval is in the scale you’re playing and then try changing it. For example if you know a Major scale…

… you should be able to adjust particular intervals instead of thinking of a brand new scale. Take Harmonic Major, for example, where the only difference is the b6 interval:

It is almost identical but with a fret lower for the 6th note in the sequence. You should know your intervals and notes across the fretboard and how to manipulate them, but referencing to common scales should make it easy to apply some of the foreign palettes in the list above.

Application

To create tension, as discussed in lesson one, you have to play a note that clashes against the chord tones and extensions of your harmony. To begin with we will continue working with an A minor vamp. Over an A Minor (Dorian context) our consonant intervals would be: R 2 b3 4 5 6 b7. Our dissonant intervals would be b2 3 b5 b6 7.

In essence you could play any palette over A Minor, as each will produce a different effect. The trick is knowing how far ‘out’ each one will take you. Generally, a good rule of thumb is to begin with the palettes that contain the triad from your harmony to ensure that the chord is not completely lost. Here is a selection:

| Name | Formula |

|---|---|

| Melodic Minor | 1 2 b3 4 5 6 7 |

| Dorian b2 | 1 b2 b3 4 5 6 b7 |

| Locrian ♮2 | 1 2 b3 4 b5 b6 b7 |

| Dorian #4 | 1 2 b3 #4 5 6 b7 |

| Dorian b5 | 1 2 b3 4 b5 6 b7 |

| DH mode 6 | 1 #2 3 4 #5 6 7 |

These are your first port of call when playing outside over a minor vamp like this. Once you have tried playing some of them, the next step is to try the palettes that take you even further outside:

| Name | Formula |

|---|---|

| Lydian Augmented | 1 2 3 #4 #5 6 7 |

| Locrian ♮6 | 1 b2 b3 4 b5 6 b7 |

| Super Locrian | 1 b2 b3 b4 b5 b6 b7 |

| Lydian #2 | 1 #2 3 #4 5 6 7 |

| Super Locrian bb7 | 1 b2 b3 b4 b5 b6 bb7 |

| DH mode 3 | 1 b2 b3 b4 5 b6 bb7 |

This list includes palettes with the major 3rd, as well, which is really effective at creating tension here. Be careful, as the closer you get to a straight major scale the more it will sound like you are playing the wrong notes, rather than playing ‘outside.’ This is again due to our aural conditioning, as the sound of the major scale, and even its modes, is so strong that it is hard to detach its connotations.

You may have also found that the Aeolian and Phrygian modes were lacking in the ‘outside’ sound. Again, this is likely due to the way we perceive those notes in sequence. The less heard palettes – melodic, harmonic and double harmonic are not ingrained in our ears as strongly and so do not delineate the A minor as much, or at least in the same way.

Here are some examples of these scales in use. Remember about phrasing outside playing – it should lead out, but ultimately lead back in to strengthen the harmony.

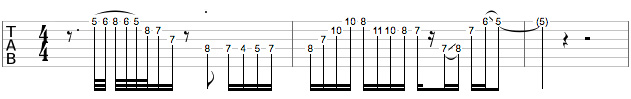

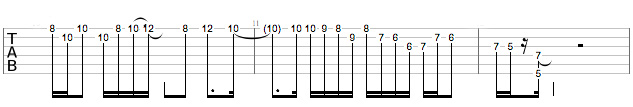

EX 1. Dorian b2

Using the b2 here only delineates the harmony slightly, but enough to give an interesting outside sound. The jagged rhythm with lots of 16th note rests can add to the dissonant feel, when used effectively.

Ex 1

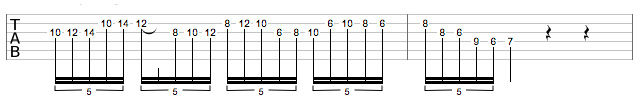

EX 2. Dorian b5

This palette is effective in evoking Scott Henderson’s sound. The double stops in half – whole – half interval slides are very typical of his later blues style and are a great way of sounding outside in a more controlled blues context.

Ex 2

EX 3. Locrian ♮2

This is a slightly weirder example, shown here in a kind of bebop-style 8th note lick. This works well in many situations – over the ii, V in Major or even as a resolving idea in a Minor ii V.

Ex 3

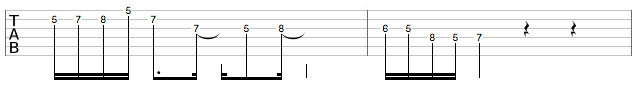

EX 4. Double Harmonic mode 6

This palette is extremely hard to use as its intervals are so acute and clashing. It generally works well when there is little harmony underneath it, other than Roots and 5ths.

Ex 4

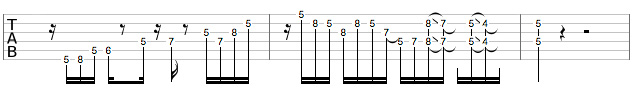

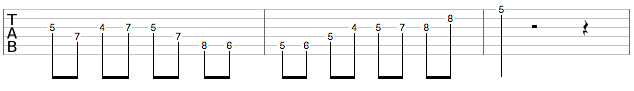

EX 5. Lydian Augmented

This is a sequenced lick derived from the Lydian Augmented scale – it sounds very much like a whole tone scale and can be used with irregular rhythmic groupings to create an altogether different time/feel/mood over what you are playing.

Ex 5

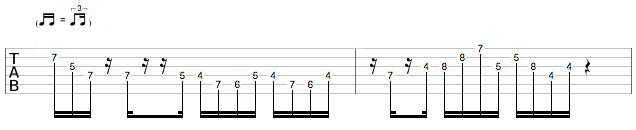

EX 6. Super Locrian

The start of this lick leads from A dorian, then uses the Altered Scale or Super Locrian scale to create quick moment of tension, and then resolves back to the root. This approach can be used over a V chord in a ii V I.

Ex 6

EX 7. Dorian #4

In this example, I’ve used a swing rhythm and extracted some arpeggios from the Dorian #4 palette to create a Michael Brecker style lick that sounds like it is modulating.

Ex 7

Above all, keep practicing your intervals so you can call on any of these palettes or parts of them at any time. While they are excellent for improvising ‘outside’ and creating tension, they can also be used as compositional tools in their own right by harmonising them to create interesting chords and harmonies.

Here is a final track with my application of the concepts within this article:

Full Track

GUITAR MESSENGER FULL

Backing Track

GUITAR MESSENGER 2 backing

In the next lesson, I will discuss using symmetrical patterns and palettes to create outside tensions.