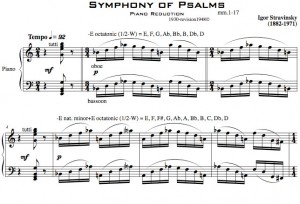

Hello and welcome back to Beyond Theory. In this column I would like us to get away from THEORY altogether and look closer at texturing and things approximate to the realm of composition. Over the course of the last few years I have come to realize that most people do not truly appreciate how versatile the piano can be when writing for it. By versatility I do not mean styles of music at all, but actually how the piano can be utilized to play many different lines and textures at the same time – its polyphonic capabilities.

For the purpose of this column we will be looking at small fragments from different works out of the piano repertoire. In those examples we will see how each composer has decided to treat the given texture and in what way he has or has not attempted to expand the writing to go beyond mere melody and accompaniment. I should stress from the beginning that the purpose of this column is not to prove that mere melody and accompaniment is bad or amateurish (after all many great works have been written in that way), but simply that in this column we will be looking to expand what most people view as physically possible on the instrument from the stand point of polyphony. This will hopefully lead to more freedom when approaching composing for piano or synthesizer, and even expanding what some readers view as possible when writing for any keyboard instrument.

Melody and Accompaniment:

Everyone here has seen this sort of piano writing:

1

This is usually what a beginning student in composition will put together as they are trying to compose for the piano. A held over chord or left hand figure and a right hand melody, essentially 2 elements, in this case being that one is a line and the other a simple harmonic figure.

How can one expand this sort of texture to include something more? After all, a person only has 2 hands, how are they to play something more complex than this? Here is an obviously much superior example, taken from Chopin’s Nocturne in Bb minor op.9

2

You see here, Chopin is using a very simple texture as well – the left hand outlines chords via arpeggios and the right hand plays a melody. Already, however, you can see how superior his writing is to the pervious example. While it can be said that he is simply approaching the writing like the example that came before it, his control of how we hear said texture is much superior (part of the reason is Chopin’s use of compound lines in the left hand of said texture, but let us not look at that so closely right now).

As previously stated, Chopin outlines his harmonic progression via arpeggios in the left hand, and in addition to that also sets up a TONIC PEDAL in which he grounds the tonic of the piece firmly in the mind of the listener awhile outlining the very simple tonic-dominant harmony. Meanwhile, in the right hand he has the lyrical melody and some ornamental variations on it, again slightly more worked out than our first example awhile still retaining that very same idea (melody and accompaniment).

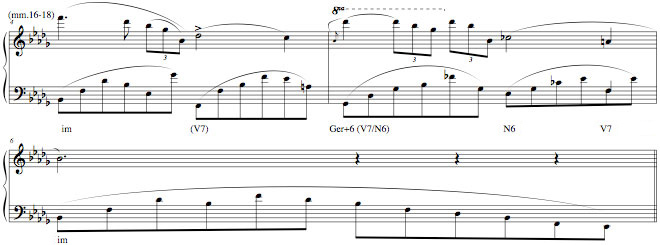

3

In the example above Chopin retains the same principle, left hand outlining chords and right hand melody. However, notice he no longer has the Tonic Pedal going and instead is shifting to accommodate new harmony. The harmonic progression here is interesting, and I thought I would point it out: im – (V7) – Ger+6 (V7/N6) – N6 – V7- im. (For clarification on these chords please address questions in the GuitarMessenger Forum)

2 part, independent counterpoint

Briefly, let us now look at a 2 part texture where both lines are totally independent from each other. Awhile it is true they still interact together to form harmony one is not perceived as mere harmonic accompaniment awhile the other is heard as melody; in this case both lines are heard as totally independent. JS Bach was a master of counterpoint and the following example shows how he controls multiple lines to weave together harmonic textures from a purely linear standpoint.

Bach’s Fugue No. 10 in E minor (Well-Tempered Clavier Book I)

3+ part independent counterpoint

3-part:Bach’s Fugue No. 2 in C Minor (Well-Tempered Clavier Book I)

4-part: Bach’s Fugue No. 18 in G# Minor (Well-Tempered Clavier Book I)

This is not the column to talk about FUGUE in detail, which is something I plan to cover later on in a future column. Nonetheless, these are great examples of counterpoint and it becomes clear how precise Bach’s control of independent lines really was. If you follow all the fugues, you can clearly see how he manipulates each one so that the listener is constantly engaged by at least two melodies or more, awhile in the case of 4-5 part fugues the other voices will usually fill out remaining harmony. Sometimes all 5 lines will be totally independent within the texture, as is the case with this example that follows: a 5 part fugue in which the subject is canonically stated in stretto (meaning that the theme will lap onto itself in all 5 lines).

5-part: Bach’s Fugue No. 22 in Bb Minor (Well-Tempered Clavier Book I)

Godowsky – the Buddha of Pianists

A composer who pushed the limits of what was thought physically possible on the piano was Polish pianist/composer Leopold Godowsky. One of his most famous contributions to the piano repertoire are the Chopin-Godowsky piano transcriptions, of such monstrous difficulty to be considered impossible when they were originally published.

Taking the thematic and rhythmic structures found in each of Chopin’s etudes (op.10 and op.25 – as well as the concert etudes) Godowsky re-transcribed them to the piano, turning them into studies on the utmost physical limits of polyphony for his time. Making multiple versions of various etudes, Godowsky ends up with 53 etudes of which 27 are written for the Left-Hand alone. Godowsky goes as far as combining and superimposing some etudes to create single studies out of multiple studies.

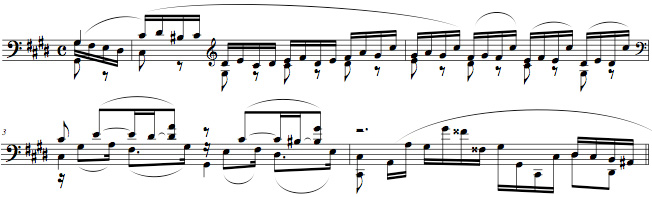

Consider how Godowsky compacts the material found in Chopin’s 4th etude from op.10 from a two-hand texture to a single hand (Left Hand Alone) texture that still has the same aural effect. Outside of the sheer physical difficulties the texturing presents, it musically holds up against the original, and we do not perceive it as being one hand at all – but actually are fooled into hearing it as if it is being played by 2 hands.

godowsky

Reger, Sorabji and the Organ

Moving on in our quest to expand how we view keyboard texturing and how to expand the typical melody and accompaniment type writing that seems to limit most composers who are new to keyboard writing, let us take a look at a great example from the late romantic era composer/organist/pianist Max Reger.

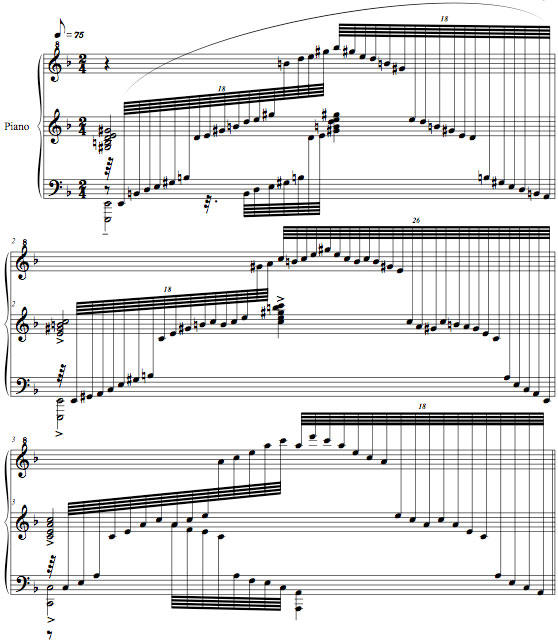

Reger being a great organist manages to create a quasi-organ texture on the piano by doubling key voices at the end of the final double-fugue of his masterwork “Variations on a Theme by J.S Bach op.81”; he further creates this illusion by shifting registers so that the listener is forced to hear the entire sonic spectrum of the piano at the same time. The effect is that of multiple pianists playing said part.

Notice how much more chromatically dense Reger’s music is than all previous examples, one of his trademarks as a composer was his dense chromaticism and total contrapuntal control – a true Neo-Baroque composer if there ever was one. Take note, that awhile this texture is very thick it is still part of a 4 part fugue. Starting towards the end of the fugue, Reger begins to voice important contrapuntal lines in octaves; the power of the texture goes closer to the nature of the organ and such doublings are common… 8va doublings for power.Continue to the next page to view the score.

Reger’s “Variations on a Theme by J.S Bach Op.81”

Reger example

Sorabji and the Transcription

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892-1988) is one of the most obscure and interesting figures out of the XXth century. Primarily a pianist-composer he actually discouraged performances of his own works because of his constant worry that no one would be able to do them justice, practically being a hermit did little to help his reputation as a composer and pianist to the average music fan.

Like Godowsky, Sorabji was a great advocate of piano transcriptions – with several important works of his being represented by that medium. In the following example Sorabji (like Reger before him) approaches the texturing for one of his piano transcriptions – Chromatic Fantasy & Fugue by JS Bach – as to imply its original sound as heard on an organ.

Sorabji does not make a direct note for note translation of Bach’s original score, but actually re-writes it as to imply a sound closer to that of the organ. Notice how Sorabji asks that the chords be held over for the entire 2/4 bar; the intention is to create the effect of a constant pedal underneath the arpeggiated figures, either the notes are re-attacked or they are constantly ringing.

Sorabji example

I hope the first installment of this column will help expand what you view as possible when writing for the piano or synthesizer. Furthermore, I hope it gets you to think more closely about what we perceive as possible on any instrument. The second installment of this column will deal with other advancements made in regards to writing for the piano, but for that column I will deal specifically with works that are non-tonal and/or come out of the second half of the XXth century. Planned for that column is a brief look at the piano music of: Ligeti, Stockhausen, Xenakis, and Messiaen.

If there are any musical terms in this article that you are unfamiliar with, I recommend visiting Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary. And remember, always feel free to ask me any questions you might have regarding this lesson in the Guitar Messenger Forum.

Roberto’s currently listening to: Vuk Kulenovic – Concerto Ostinato (Piano Concerto n.03)