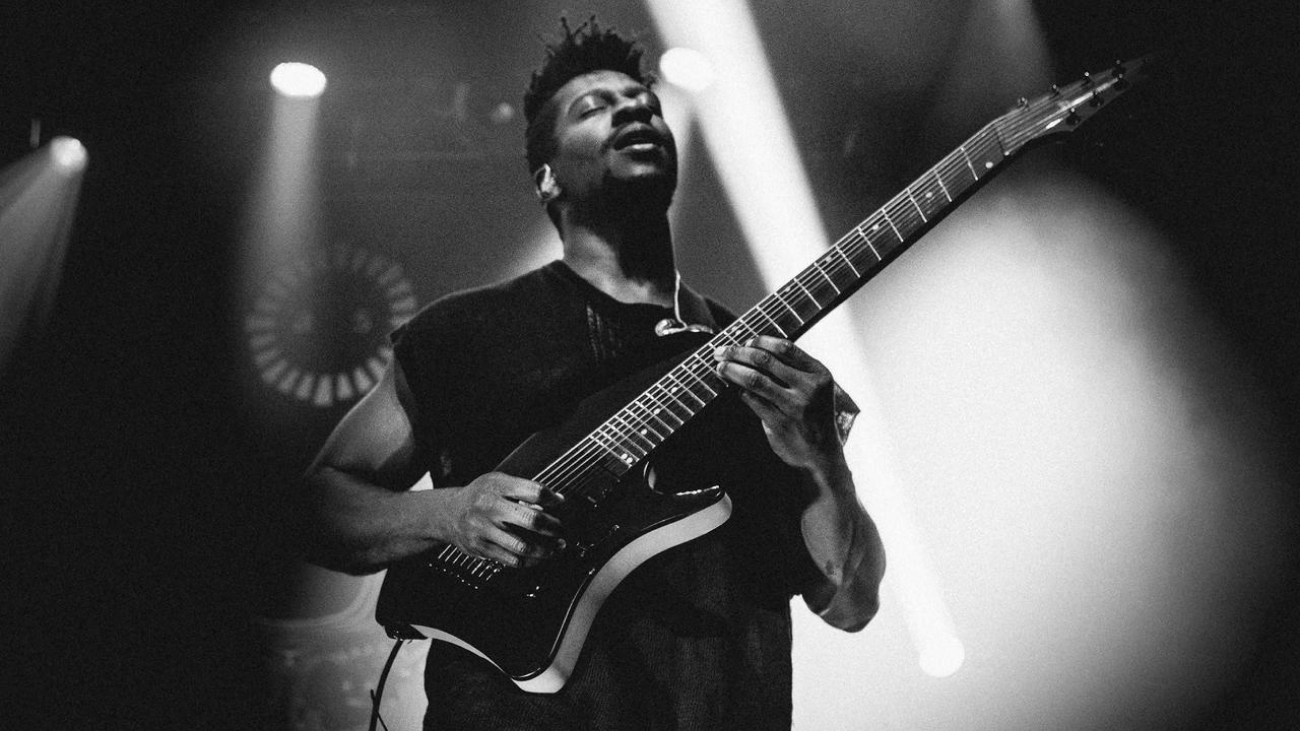

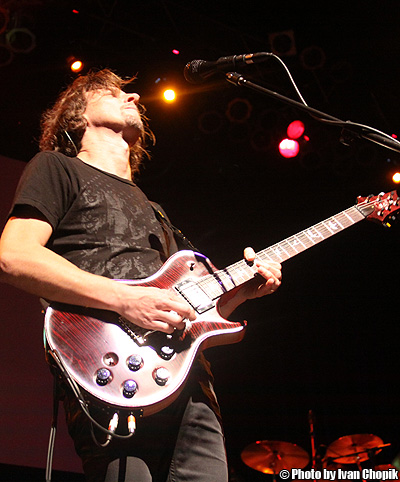

Musical nomad Pierre Bensusan discovered the guitar in his early teens, and it wasn’t long before his home-crafted skills earned him critical acclaim at the prestigious Montreux Jazz Festival. Since then, Pierre has assimilated musical threads from across Europe and beyond into his style – his ears deftly weaving folk standards and original compositions into a lush acoustic tapestry dyed with jazz, latin and gypsy hues.

Musical nomad Pierre Bensusan discovered the guitar in his early teens, and it wasn’t long before his home-crafted skills earned him critical acclaim at the prestigious Montreux Jazz Festival. Since then, Pierre has assimilated musical threads from across Europe and beyond into his style – his ears deftly weaving folk standards and original compositions into a lush acoustic tapestry dyed with jazz, latin and gypsy hues.

On his latest release Vividly, Pierre stretches his boundaries even further – incorporating not only his own voice but exotic percussion, choruses, and even a Chinese violin. The resulting compositions are not simply world music, but music of the world. I was fortunate enough to sit down with Pierre and speak with him about the finer compass points of his bold sound, the thinking power of fingers and the spell of Bob Dylan.

LD: You’re a few nights into your American tour. How is it going so far?

PB: Great. It’s cold, especially with the wind in New York, but the audience is warm.

LD: Going into the process of making your new album Vividly, what were some goals and inspirations that you were looking to bring out?

PB: I was revisiting a lot of things that were in my cupboard for a while, which I had put aside for whatever reasons. Sometimes it’s just a matter of finding the proper time to attend to it and give the proper attention. Two years ago I started looking into really making this album. I didn’t have a set plan – the tunes, the songs, and the instrumentals sort of jumped out of the water and said: ‘Me! Me! Me!’ So I took the 14 first ones, cut them, and worked on them.

I felt pressure to make this record. I had to work with deadlines. In the end it was very challenging to meet the deadline – the day I finished mastering I was going on the road to England. But I didn’t feel, throughout the two years I was making that record, the kind of pressure I felt for instance before Altiplanos. I recorded at home, on my own timing. I would call an engineer whenever I needed one. For this record, I felt I really spent time for each tune to come accordingly to what I was looking for.

I sing a lot on Vividly. It’s the first time I do sing a lot on a record. For a while I was listening to people telling me: ‘Why don’t you sing more?’ Then some people say: ‘You should do only guitar music. It is much easier to market you like this.’ Other people say: ‘You know, you have a beautiful voice, but you should not sing text because it takes people to a different place. Just the sound of a voice without any meaning to it is much better.’

Once you hear every comment and every critique, and all the good feedback and negative feedback, you sort of do your own alchemy, naturally, over the years. At the end of the day you have to do what feels the most in keeping your integrity. So that’s how I look at that record: I mean every note of it. Every word, every intention, I can sign and put my name there.

LD: Vividly is a very well-rounded mix of musical settings: instrumental solo guitar, a lot of vocals for the first time, and also some percussion. As you were working with the songs, how did you decide which ones were going to stay just instrumental and which ones to put lyrics to?

PB: Since three records, Intuite through Altiplanos and then Vividly, my aim is to make a surrounding that works with only guitar and voice so that I don’t depend on anybody to go on the road and perform songs. I see the limit of this, of course. The limit is I listen to something and think: ‘Oh God, I should have asked a string quartet to join me or I should’ve had so-and-so sing with me.’ But it has to work on the guitar, so I consider this instrument like a little orchestra. I cannot play everything, but I can suggest that some of those things are there, such as a full harmony treatment, such as all of a sudden more hits to the harmony or more amplitude to a new segment so that we feel elevated – and that can be done. It can also be done with an orchestra, of course. You write a score and all of a sudden you create more colors, and all of a sudden all those things are there.

But on a guitar there are also ways to do it. It’s an intention that can be materialized by different ways to touch the strings with the right-hand, by different vibrato and also by the voice. So the color of the voice plus the color of the 6 strings: 7 strings altogether – in fact 2 strings of the voice, so 8. You can make a lot of music with that! So still, one more time: this is about suggesting an environment, and I think I did succeed in doing that. Although there were a few times on the record where I brought in guests.

But on a guitar there are also ways to do it. It’s an intention that can be materialized by different ways to touch the strings with the right-hand, by different vibrato and also by the voice. So the color of the voice plus the color of the 6 strings: 7 strings altogether – in fact 2 strings of the voice, so 8. You can make a lot of music with that! So still, one more time: this is about suggesting an environment, and I think I did succeed in doing that. Although there were a few times on the record where I brought in guests.

On two songs [‘The In-Between’ and ‘La Blanche Biche’] I had to invite this musician from China who I met on Reunion Island. His name is Gan Guo – he plays a traditional Chinese violin called the erhu with two strings. When I heard him play I knew I had to invite him. He’s playing beautiful melodies and it’s not a violin. When you hear it, you know it’s not a violin and you wonder: ‘What is it?’ and I like that. I like that you know it’s a stringed instrument with a bow, but it’s not a violin – and yet it is something very familiar.

On ‘The In-Between’ I did the bass and some percussion, and then I had my friend Franck Stibon play keys. I recorded my album Spices for CBS with him back when I had a full band. We had lost track for years and we bumped into each other in Paris in the street. I invited him home and said: ‘I need some keyboards there. Can you do that?” In only one hour, he put down a few layers of keyboards.

At first with ‘Les Places de Liberte’ I thought: ‘Okay, I’m going to do something with just guitar and voice.’ It was a very demanding guitar piece, and when you think that you have to add the vocals on it, it’s like: ‘Phew.’ I wanted something that sounded very Cuban, and the words are about a question that I asked about where my country is going in terms of tolerance, in terms of religions, in terms of how we treat people and what we do to each other. The Latin element was a sort of color which is already so connected with revolutions, with political statements, so that had to be there.

But, you know, on one guitar, when you consider what’s all there: playing the bass up front, a bit before the beat, and the chords, and the singing… it was quite challenging. The more I was doing this, the more I felt I could not be alone on this because I needed other voices. I needed children to sing. I needed women to sing. I needed percussion. I needed a bass.

I wanted this thing to be more generous, because guitar and voice sometimes is very austere. It gives this impression of sparsity, which is great because I think when you play the guitar you have to go to what’s essential because you can do so much with movements, with placements. For ‘Les Places de Liberte’ I really wanted to have a full environment so I invited singers, percussion, trumpet, and flugelhorn. That’s the only song that is so produced on the album. Everything else is very sparse.

LD: Let’s take it back a bit and talk about the development of your style. You have a unique approach to the guitar: how it’s played and how you bring out your music. It’s all fingerpicking, but it’s not strictly classical – it incorporates a lot of Gypsy music, jazz and traditional Irish tunes. You started off playing piano, and then picked up guitar and taught yourself before you were a teenager. What first inspired you to find your own voice on the guitar?

PB: Bob Dylan [laughs].

LD: Any particular album or era?

PB: Nashville Skyline, the album with ‘Lay Lady Lay.’

LD: What about his playing inspired you?

PB: It’s not even about his playing or his singing or his voice, it’s the music of everything. His words, for me, are like an organic jewel. It’s not aesthetically beautiful; it’s a bit abrupt. It’s an inner beauty. You feel this beauty when you hear it.

The words, what he says, what he sings: that really gave me the idea that I wanted to play the guitar, so I started to play and sing a lot of songs by a lot of singer-songwriters from France and from England. My first years as a guitar player were playing chords, accompanying myself, and singing.

I came from piano and played a lot of classical music for four years. I was sight-reading. But when I took up the guitar, I didn’t even know how to tune it or to change strings. Eventually a friend came and showed me how to change strings, how to tune it, and a few chords and that’s it. I played in standard tuning for several years.

At school there were people a bit older than me listening to Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, so we thought we’d get together and work out those harmonies. We started a quartet and rehearsed twice a week. Gradually we started to become more instrumentalists than singers. They also introduced me to the music of Pentangle and for me that was a revelation. From there I started to listen to a lot of country blues – people like Big Bill Broonzy, Rev. Gary Davis, Mississippi John Hurt, Robert Johnson. I was really going into that direction, so I started to play in alternate tunings with blues, playing a bit of bottleneck, discovering Ry Cooder.

The summer I was 15 I took my guitar, I lived on the beach and sold ice cream. It was amazing. My parents allowed me to go hitchhiking to this folk festival in Britain. It was 200 km from where we were, and I told my friends I was going to be away for three or four days. I hitchhiked to that folk festival and there, to make a long story short, I met some amazing musicians from Britain and Ireland. That was a revelation and a shock – the beauty of those melodies.

I started to listen to a lot of that and obviously I wanted to bring a lot of that to the guitar. I started to work on adaptations of Irish music in different tunings. As I am self-taught, I didn’t really spend much time in standard tuning at all, maybe about three years. Then I started playing about 10 different tunings until 1978.

By ‘78 I had already made two records, and I had started to become really confused with all those tunings. I was functioning by heart, but I was not functioning as a spontaneous musician. I did not know my chords. I felt that something was not right, because the problem with alternate tunings is that if you do not study your fretboard, you depend only on what you know and end up sounding like everybody else.

So I chose DADGAD, which I had already used quite a bit in my adaptations of traditional music from France and Ireland. When I made that decision my life became so much simpler: one tuning, and the capo when I wanted to change key. Little by little, I started to have a more academic approach. I looked at classical players and flamenco players.

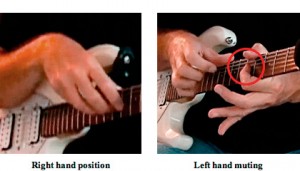

I looked at the right hand, as I felt mine was completely atrophied. I thought my thumb with a thumbpick was okay, but I was in fact always getting the same tone and it forced my hand into the same position. As a result I could not really vary tones and approaches. It’s like someone who smokes and wants to quit: it’s very difficult to do it right away. I started to study my chords, my scales, modes, harmonies – until I completely forgot I was playing in a different tuning.

LD: You have transcriptions of a lot of your tunes, and you make them readily available to the guitar community through the Internet and your own books.

PB: There is nothing to hide, right?

LD: Do you find yourself writing out a lot of your tunes before they are recorded, or do you go back and analyze what you’ve done?

PB: I do both. Sometimes I record it and think: ‘How am I going to write out that stuff? But recently everything I’ve played has been written before, though it is the result of different improv, different phases, different periods of my life which led me to arrive at a piece which I consider ‘not finished’ but ‘working.’ In a certain context it works. A tune is only one picture, but there are many ways to look at the music. A tune is an organized world, a very synchronized world. As long as the essence of what is conveyed in the piece is preserved, you can do absolutely what you want. That’s what they do in jazz with standards.

When you play solo guitar it is difficult to work with this paradox. On one side you learn everything by heart so that you can forget. You can make unpleasant fingerings become comfortable because you work hard on them. By doing so you automate all those movements with your fingers and then the fingers remember – they have a memory of their own.

Yet you can forget everything and try to work more as a freethinker, to go away from chords and from all those patterns which have been repeated and rehearsed and be a little bit more adventurous, and still keep the essence of what you are trying to say with the music.

I work in both directions. With my new record [Vividly], Altiplanos and Intuite, most of the songs were written. But when I play live, I revisit some of those things. Not all of the time – it depends on my confidence, the sound, the mood, the vibe of the audience. But I try to put myself in a situation to take chances and try to make it manageable. I think it’s important to take chances. If you live in the comfort zone and you want to stay there all the time, you’re not helping yourself. Although it’s debatable, I guess.

LD: In the mid-80s you published The Guitar Book, which is one of my favorite guitar method books, because it addresses not only the guitar but music in an artistic life. It incorporates poetry, drawing, technique and even recipes, along with painting and photography. Could you talk a little bit about how those disciplines open up to you through the guitar?

PB: It’s not just to the guitar – it’s all there. The guitar is just part of that thing. The guitar did not open my eyes on life, life opened my eyes on the guitar, among other things. I always felt I played the guitar because I had nothing else to play. The guitar happened to be there.

I hated it at first. I didn’t know how to tune it. I couldn’t play it like the piano. I felt so frustrated with that thing. It was hurting my fingers. It was difficult to get that beautiful pitch that you get with the piano. And I felt that: ‘I don’t like it. I don’t want that. I should go back to piano or do something else with more notes, more possibilities.’ When I heard those people like Dylan, that gave me a tender approach to the guitar. I started to look at it with affection. I started to say: ‘Well, maybe we can be friends.’ What I liked about it was that you could take this instrument anywhere, so all of a sudden you could function as a musician everywhere – not only when you have your piano with you, which is rare.

So I started to have my guitar with me all the time, and I started to be identified as ‘the guitar player.’ I would arrive somewhere and I’d sit and take my guitar and play and play and play and play. Some friends, after trying to talk to me for a few hours, would leave because I was just not available. That made me realize how addictive this instrument is. In order to make it talk, to feel comfortable with the technique, to improvise, I had to play all the time.

The more I play, the more I know that I have a lot of things to learn, and the more I can feel that I am expressing something of my deeper being. That helps me to open my eyes and my heart to everything else – everything that gives me a chance to become a better person, every piece of art. This is why in my book I felt I had to go in that direction and to say: ‘This guitar is only an instrument.’ We use an instrument to create something, so everything else is instrumental, too.

LD: Where do you see yourself developing next?

PB: To become a better player, definitely. I still have so much to look into. There is still so much music there that I want to play and that I don’t play.

LD: Like what?

PB: Hearing something in my imagination that is perfect. It’s there, but I don’t want to keep it for me. I like to at least prove to myself that I’m able to play it out loud. I could sing it, but I think that it’s also very important to go through the effort of putting it on an instrument, to overcome the difficulty of making it pleasant and easy.

Whatever we do on the instrument, whatever we see is abstract. It’s only the music. It’s not fingers moving, because anybody can spend time and move his fingers. They only move because of an intention, because you command them, so it’s not about the fingers. A lot of guitar players are confused by that. They forget that they’re there to play music, not to play guitar. They end up playing a lot of guitar, but very little music.

But that’s debatable once more. How can you tell someone that what they do is not musical? It is such a personal statement. I think this is the kind of thing that a person needs to see for himself or herself whenever the time is right. We get confused, because we work very hard at technical things and think that because we feel ‘That’s it, I can do it!’ we are in fact making a musical statement, when in fact we are not doing that.

It showed me that the music is somewhere else, and that everything we do with an instrument is a sort of pretext to get to a place that we call music, but we don’t really know what it is. The music is a resonance, it’s a vibration. It is something that is very difficult to define, and maybe this is why we play and not talk.

LD: As you continue to develop and explore music, what goes on through your head? Are you thinking about technique? In your book you think very analytically about which fingers you are using – using the thumb and the pinky in really unorthodox ways. Is that all automatic to you, or are you developing new techniques?

PB: Over the years I’ve been completely changing and revisiting my technique – I used to play the thumbpick, I used to play with no nails – I also used to not use my ring finger. I incorporated all those elements little by little, and so my technique is progressing all the time – mostly my right hand technique. My left hand technique is following what my right hand can do.

I am very aware of fingerings. I think they are key in expressing music. The fingerings have to be right. Otherwise you are late or very tired, and either one of those elements shows up in the music. When you spend a tenth of a second in a situation where you should not be, that is a tenth of a second when you’re losing time in the music. When you’re tired because you are overdoing something instead of finding a more rational and easier way, a more ergonomic way to play it – that also shows in the music.

Pierre Bensusan and Luke Dennis

Every aspect of a lack of attention to those details means you pay cash, musically speaking. That really forced me to look into doing the best I could – with tone, with how I touch the guitar. The more I play, the more I think I have a classical technique. I think after a while all the roads lead to Rome, so to speak. What is the most ergonomic way to play? What fingers? How do we address the strings?

A lot of the classical technique is also very good on the steel string guitar. You can play a rest stroke on a steel string and it is going to sound very warm and smooth and wide – same with the thumb. Leo Kottke changed his technique – he went from using picks to using nothing.

The fingertip contact makes you closer to your instrument, and then you end up playing with more nuances. You start feeling them because there is no alien quality between you and the instrument. That’s my conception. I’m open to a lot of the conceptions, but for me this is what has worked the best. So I’m looking all the time, finding things that open new doors for me. It’s going to be this way until the last minute of life, I think.

[*Special thanks to Matt Smith and his crew at the wonderful Club Passim and the Passim School of Music for their warm hospitality!]