Having covered the ins and outs of his musical past, present, and future in parts I-III of our interview series, Paul Masvidal now opens up about the non-musical forces at work in his life and the merits of art that ‘argues with itself.’

Part I | Part II | Part III

PHILOSOPHY

LD: The one thing that always just seems paradoxical about your band is your very pervasive sense of positivity, consciousness, and cosmic understanding that comes across through your lyrics, but at the same time you’re called Cynic. It seems almost like a cynical name to have for yourself. Can you speak to the name?

PM: It’s funny; we put the definition of a cynic in the liner notes of Focus, because I was so concerned with the bad rep that the modern ‘cynic’ name has gotten. I wanted to show people what the original cynics, Diogenes and Antisthenes, were doing back in the day. They were like the yogis of ancient Greece. Their whole philosophy was that happiness is not externalized. It’s not out there; it’s an internal experience. They lived like homeless people and still maintained this sense of dignity and presence. They were just like, ‘Look, we don’t have all the things you guys have. We’re basically dirty, homeless people and yet, we are perfectly fine. I feel clear. I feel stable. I feel aware and awake and happy.’

Their whole thing was that virtue constitutes happiness and the essence of virtue is self-control. The whole thing was rooted in something to me that was almost Buddhist. One of the stories about Diogenes is that he would walk around ancient Greece in broad daylight with a lamp. The famous question was, ‘Why are you holding a lamp in broad daylight?’ He said, ‘I’m trying to find an honest man.’ You think of the modern cynic as someone who questions someone’s motives, who questions the truth in a situation. There is the root of it, how it’s misconstrued into somebody who’s a doubter.

I don’t really think that was the whole view of cynicism. Cynicism was more about a sense of discipline in order to know thyself and attain happiness. I got so caught up in that for a while. The roots of cynics, they were like yogis: really cool guys talking about really interesting things. But over time, it became like a snarky intellectual disposition to be a cynic. At this point, I feel like it gives us an edge or something. You almost think it’s a punk rock band or something.

Originally, I just liked the name. I remember I gravitated towards it even before I knew what it meant just based on how it looks. It was framed by two C’s with this ‘YNI’ in the middle. I liked the way that it sounded. It was just one of those things that was like, ‘ooh, cool!’ as a kid when I connected with it. Then I did more research and I was like, ‘Ooh, it has really interesting meaning. There’s all this philosophy surrounding it!’ In some ways we’re more true to the origins of cynic than ever. We’re singing the praises of what the cynics were trying to say, even though the word’s meaning has shifted and taken on a more negative kind of thing.

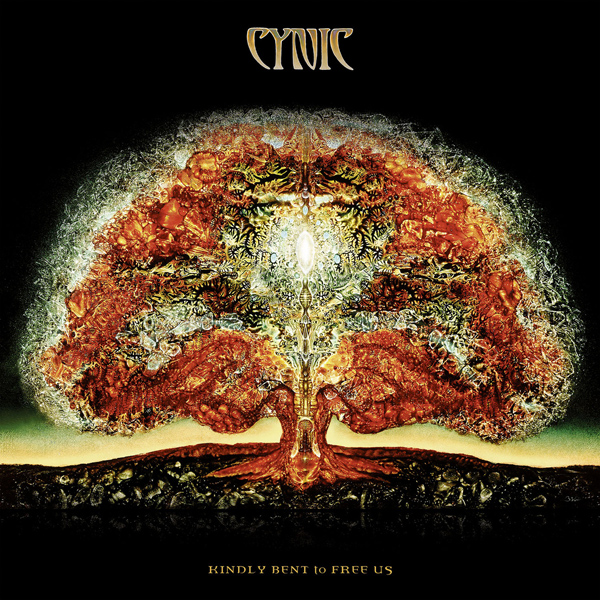

I see it like that’s part of the contrast. In some ways it’s weird to see, for example, the psychedelic Robert Venosa painting and then ‘Cynic.’ I love that. It challenges things and makes you ask questions. It’s doing art that argues with itself. I like when that happens.

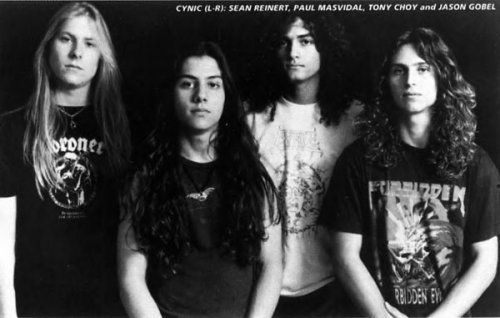

The early days of Cynic, circa early 1990s. From left to right: Sean Reinert, Paul Masvidal, Tony Choy, and Jason Gobel.

LD: There’s an Alan Watts sample in ‘Moon Heart Sun Head.’ Were there other non-musical influences that you felt helped inform your approach to this album?

PM: Oh, yeah, man. Every song has some reference point to something I’m practicing in my life – either spiritual practice, or something I’m doing to expand my knowledge of who I am or enrich my path as a person. There were different kinds of perspectives going on. For example, ‘Gitanjali,’ a direct reference to a book of the same name, is about a girl. She was a sixteen-year-old girl from India who had terminal cancer. She secretly wrote a bunch of poems as she was dying and hid them all. Her mother found them after she died and they’re like Emily Dickinson’s writing. It’s phenomenal, really wise, beautiful, transparent kind of stuff.

She was named after a book called Gitanjali by Rabindranath Tagore of India who won the Nobel Prize in Literature. I thought she was channeling his wisdom, because at sixteen, how could she have this much life awareness? Some things are directly referencing that kind of stuff. I’m a big fan of Chögyam Trungpa, and ‘The Lion’s Roar’ was a lecture he gave about navigating yourself, navigating reality, and working with certain energies.

I worked it into ‘Mood Heart Sun Head,’ too; how essentially all our intimate relationships are spiritual practices. They’re mirrors, essentially, and opportunities for us to see who we are. ‘True Hallucination Speak’ is very inspired by Terence McKenna, the psychotropic author who wrote Food of the Gods and True Hallucinations. I saw him speak a couple of times back in the day and I became good friends with him. He’s just one of those people that was so incredibly intelligent and tuned in to another dimension, another level of vibration in the way that he saw the world and communicated. I’ve always been a big fan of his, so I directly referenced some of that inspiration mixed with my own interest and curiosity in psychotropic medicines and shamanic stuff.

Every song has its own very specific little thing and the through-line, I think, on the whole record, is the mind – a relationship to one’s own mind. That’s why the cover is kind of a brain. It’s three things: a brain, a mushroom cloud, and a tree, but they’re all interrelated.

Kindly Bent to Free Us – Album Cover

[Special thanks to Carl Frederick of Blazing Metal Photography for allowing us to use his outstanding live photo of Paul Masvidal].