A mere decade ago, Cynic was somewhat of a password between fans of extreme metal – a secret handshake that itched at a curious footnote to the 90’s Florida metal scene. But in 2008 the band reformed to make a prodigal return to a world that finally seemed to have caught up with their high-minded 1994 manifesto Focus.

A mere decade ago, Cynic was somewhat of a password between fans of extreme metal – a secret handshake that itched at a curious footnote to the 90’s Florida metal scene. But in 2008 the band reformed to make a prodigal return to a world that finally seemed to have caught up with their high-minded 1994 manifesto Focus.

Having exhausted itself on the harder-faster-louder mantra, the metal community has since grown its ears out to explore a more balanced diet of dynamics, texture and rhythms. Themes of Eastern mysticism, consciousness, and polyrhythms are now no longer anathema to the black-clad brethren. And while it’s rare for a band to change so much by staying the same, Cynic did just that when they resurfaced with 2008’s LP Traced in Air.

Thankfully, their most recent EP, Carbon-Based Anatomy, has doubled down on their pledge towards the new millennium. Lush with lofty vocal treatments, tribal rhythms, and ferocious guitar work, the 21st century Cynic is here to stay.

Guitar Messenger was able to sit down with lead guitarist and frontman Paul Masvidal at a Worcester, Massachusetts tour stop to discuss the band’s past, present, and future by way of a few ruminating detours on Emerson, architects, and the ever ephemeral process of creation:

LD: I can speak on behalf of Cynic fans everywhere when I say that I’m very glad it didn’t take another fifteen years to hear new music from you guys. What inspired the quick turnaround of releasing a new project?

PM: I think we’re just in a momentum phase right now. We toured for almost three years for Traced in Air and we’re just kind of letting it roll. It feels like that intent is open now so we’re just adhering to it.

LD: Were you writing during the Traced in Air Tour or was Carbon-Based Anatomy born off the road?

PM: I don’t write on the road. Pretty much every Cynic record is like a compilation of a lot of existing material, because I have a huge library of stuff. I’m always writing when I’m home. When we’re going to make a record, we’re either pulling from an idea that’s 50% there and we’ll try to finish it or it’s some stuff that’s very realized already. So it’s kind of a ‘best of’ from the pool that makes each record.

LD: More so than on any of your past releases, your guitar playing on Carbon-Based Anatomy is much more textural than riff-based. How do you feel your role as a guitar player influences your role as a composer and vice versa?

PM: For me a guitar is just another tool for whatever the song needs. For some reason, this particular recording felt like it needed a lot of little pieces and layers to complete the image. It was funny because after we finished mixing this I had this fantasy – I was like, ‘the next record is going to be just one guitar and a lot of vocal layers.’ I say that now, but who knows?

But I’ve always been a fan of textured, layered stuff – that kind of wall of color that isn’t necessarily as definable or riff-based. It’s just like one big tapestry that you can focus in on certain areas of without thinking about one riff. You’re just thinking about this wall. It’s really very much feeling-driven, versus intellect.

LD: In the fifteen years you spent between releasing Focus and Traced in Air you were doing a lot of film scoring for TV and movies. How did those years influence your writing process when you came back to writing progressive metal?

PM: I was taking some composition classes and studying a lot about what emotional state relates to what harmonic kind of thing, like ‘what’s the chord progression for this feeling and then all the substitutions of those specific emotional components?’ I think [Sean Reinert, Drums] and I got better at honing and articulating environments and soundscapes, which lent itself to a sound that was more feeling-driven and moody versus just aggression.

I think the more refined your ears get and the more realized you are as an artist, the better you are at articulating your feelings: you don’t really know where it’s coming from, but you can get to it better and capture it.

| Click play above to watch the video of this interview. Click the ‘playlist’ button on the top left to select between parts 1-3 of the interview. |

LD: Were there specific moods or themes you were really trying to illustrate with Carbon-Based Anatomy that you hadn’t explored on the previous two releases?

PM: Yeah. There’s definitely a more obvious world music influence coming through and probably a stronger ambient, kind of Brian Eno thing. I was really into a lot of the world music side. Pat Matheny and his record Secret Story was a really huge record for me. The opening tune, ‘Above the Treetops,’ was in some ways what I was trying to do with ‘Amidst the Coals’ – taking a traditional kind of piece and building an Amazonian arrangement around it.

There are definitely a lot of different things compared to what we’ve done before – some incredibly simple moments and then some really kind of diverse world stuff and more anthemic rock type songs. We’re just exploring, you know? We’re just enjoying the process.

LD: Touching a little more on the world aspect of the new EP, you mentioned an Amazonian feel. How do you latch onto a specific ethnic-music groove?

PM: The Amazonian stuff… I became interested in these shamanic icaros coming out of Peru. These indigenous tribes in the Amazon have this music, a form of geometric harmony and melody based on these things called icaros. They have drawings that are these squiggly lines, kind of fractal-esque looking things that are a form of written icaros so these shaman healer people will read and sing them. They call them heart songs and they undo knots in your body, places where you’re holding pain, where you’re suffering. It’s a very primitive, yet incredibly sophisticated form of medicine using sound.

Carbon-Based Anatomy album cover.

It makes perfect sense to me, thinking of music as this universal thing that’s related to the spheres. There is a sound of the planets, you know? It just really resonated with me. I had a lot of experiences in the world of shamanism, doing a lot of healing work, and when I heard these tunes they ripped me open and I thought ‘whoa!’ It felt honest, so it seemed inevitable that I would try to bring it into what we’re doing.

Then of course ‘Bija’ is a more traditional Indian style with a Western kind of slant. The interesting thing that’s happening is we’re tying it all in. There’s actually these threads throughout the EP and if you’re really paying attention you’ll hear how everything’s connected harmonically. It’s very subtle.

For example, the piano progression behind all those seas of voices in ‘Bija’ is the bridge of the title track. It’s the same changes with the same rhythmic figure. And then ‘Hieroglyph’ has a big relationship to ‘Box Up My Bones.’ Unless you are familiar with the tunes, you’re not going to put it all together. We’re just subconsciously bridging it all and making it one piece, because for me it does feel like one big idea.

Part Two

LD: How do the elements of world music manifest themselves in your guitar playing? Have you adapted a lot of this music with Eastern scales and raga styles in mind or are you just picking out the sounds across the fretboard?

PM: I’m at the point where I don’t think in terms of theory anymore. I could tell you what the scale is, but I’m really just trying to get a feeling and capture a space. Whatever it takes to get there, even if I have to do really unorthodox things, it’s just about getting this energy out of the instrument. It’s beyond intellect, I think. For me at least, it’s very kind of messy and kind of raw. It’s childlike in a way. But that’s the creative process, at least for me it is. It’s a big mess and then it kind of finds itself, you know?

LD: Was there a moment in your early guitar days when you were trying to learn Indian scales?

PM: Oh yeah. I remember I had a book of all these Indian scales. I took a few classes trying to learn a dilruba, a kind of a miniature bowed sitar. I’d like to get more hip. I feel like I got late on Shawn Lane. I found out more about him after he died, but he was doing some really cool concerts with Indian musicians and tabla players.

But it never ends. This is what’s so incredible. It’s like we’re beginners for life because it’s so dense. There’s so much music to be learned, especially as a guitar player, lifetimes until you get this thing. So we’re just kind of making our way, doing the best we can in the meantime, you know?

LD: Going back to the Focus days, Cynic grew up around this new wave of progressive death and thrash metal in the early 90s. Your lyrical adherence to Eastern philosophy and the more world-inflected solos is in pretty stark contrast to a lot of bands that write songs about chainsaw dismemberment and pestilence. Did you feel like a black sheep among the metal community or did you feel generally accepted?

PM: Back then it was not cool at all. [laughs] It was like ‘what the hell are these guys doing?’ I think at the time the metal scene was so myopic in terms of extreme music that everyone was into just being tough and brutal and we were just these geeks. We were a bunch of dorks, you know? We were just interested in jazz. I mean we weren’t even really listening to extreme metal, but we just happened to be in some bands that played it.

It’s one of those funny things that I think eventually we caught on. What happened was the death metal scene hit a brick wall and a lot of those bands realized there was nowhere to go because they were just recycling the same sound. They felt like the limitations became really apparent and they realized that the only way to expand the process of making records was to get better at their instruments. For us it was obvious because we were musicians before we were metal guys. Our priority since we were really young was just an interest in learning about music.

But yeah, it wasn’t cool at all. But people came around. We broke up and then came back around when there was a whole scene of bands singing about interesting things. I liked the brutal bands that had a twist, like Carcass that would be like medical doctors, nerdy about the gore, you know? If you’re going to do that, at least have some intelligence behind it. I thought that was kind of cool.

I think our anger and frustration that brought us to the metal scene, because there was obviously some pain there that made us connect with that kind of music, got siphoned through a different channel in terms of how it got expressed. For me writing about having the courage to love was much more brave than saying ‘I’m going to rip out your entrails and eat you.’ That just didn’t feel as cool for some reason [laughs]. But everyone’s got their own thing, you know?

LD: Since you’ve returned with Traced in Air, do you feel the metal scene is much more conducive and accepting of the message?

PM: Oh yeah, it’s come a long way, definitely.

LD: I know you felt some frustration with the music business back then in the early 90s. Are you finding it easier to make the music you want and get it heard?

PM: I think so. I mean, we’re at the point now where we don’t care anymore what anybody thinks and we’re just serving a process and trying to be honest about it. The closer I get to the truth of this process, the more people are going to resonate with it because the truth is universal, you know?

I think back then we were just being pulled in a lot of different directions because with the industry and our record company, everyone was like ‘what are you doing?’ and ‘you can’t do this!’ [laughs] ‘You can’t do that part!’ I remember that in the studio: ‘What’s going on there? Count it for me!’ ‘OK, I’ll count it for you.’ We are in a much freer place in terms of how to navigate better. I don’t know if the industry is any different, but I’m just a bit older now and it doesn’t get me. I’m just not paying attention to it and I’m focusing on other things. Back then it felt like ‘Whoa, this business stuff is too much! I just want to play my guitar!’ That was really what happened to us. ‘I just want to play my guitar, I don’t want to deal with this industry. This is nonsense!’ And it still is nonsense but now we laugh at the nonsense. It’s just a different gig.

LD: You hint at the process of Cynic moving forward as this sort of search for truth. Do you feel like there’s a lot of other artists going out there that are just searching for a lie?

PM: No, I don’t think of it in terms of what everybody else is doing. I think that everyone’s got their own process. If you want to sing about cutting people up and that’s your thing, that’s beautiful! Everyone’s gotta do what they need to do. I always feel like as long as you’re not hurting anyone in the process, then do whatever you need to do. I think the great American transcendentalist [Ralph Waldo] Emerson imprinted in me that the duty of the artist is to inspire other artists. I always found the artists that inspired me the most had a more unique voice and had something to say. I always kind of wanted to be one of those guys.

Now, what’s so curious about this process is that it doesn’t feel like it’s about you at all. The closer you get to it, the more you realize it has nothing to do with you. You’re just serving some process, and you’re just really trying to stay out of your own way as much as possible. It’s an amazing journey. I’m pretty grateful to be on it.

Part 3

LD: What artists have you drawn inspiration from through this whole journey so far?

PM: It’s funny. I keep using this metaphor of architects. One of my favorite old architects is Buckminster Fuller. He was a futurist, so cool! And Eric Owen Moss, he’s really out there, cool stuff. And then Santiago Calatrava, the Spanish architect. I think music is like sound sculpture: you are basically shaping sound molecules in trying to create these interesting shapes that you can only be heard. There is some curious relationship there. We’re always trying to create this perfect shape. It’s the endless search for the ideal design of subtraction and addition.

But musicians? Brian Eno’s been a big influence on me. I’ve been all over the map. Pat Metheny’s huge in terms of as a composer and as a guitar player. [Andrés] Segovia as a classical guitarist, just a master of classical and his interpretation of great music. A lot of fusion guys. You know, even classic rock dudes. I realized I’m a fan more of good artists than just genre or styles. I just dig great artists, you know? And painters too, like Robert Venosa. In some ways there’s been this attempt of mine to capture a Venosa painting sonically.

LD: At an aesthetic level, both Focus and Traced in Air had a very similar motif of a human-esque figure exploding into colors. The cover for Carbon-Based Anatomy is a little more nebulous in terms of what it’s depicting. How’d you choose the artwork for that?

PM: It’s funny, we didn’t. Venosa chose it. He chose it right before he passed away this past year. I had given him the background on the songs and what they were about and everything. I didn’t realize he was on his deathbed when he was doing this. His wife Martina was assisting in the communication, and he went there.

I like it, I got it later, but at first I was a bit resistant because the piece was one of his abstracts. It’s very dark and [H.R.] Giger-esque and it was just like ‘whoa, ok… We usually have these really colorful…’ But then I thought about it and I realized it made sense in terms of what this past year’s been like for us, where this EP’s being birthed from, and it just kind of had a relationship with the music that made sense later.

LD: Did you feel like you were in a darker place as you were making this EP?

PM: I was definitely coming out of, not necessarily a darker place, but a pretty hard time. Sean and I had been there and back with a lot of life change. We moved into a house together just to kind of take care of each other because we needed each other’s support. It felt like we were battling some ugly monsters out there, some dark energy. So I think the roots of a lot of pain and frustration got channeled into the EP especially the song ‘Carbon-Based Anatomy.’ I feel like the EP has a lot of complex emotions and subtext that people are going to have their own journey with. I think that’s the coolest music, when you can hear your own thing, without being too literal about it.

LD: The EP you released before Carbon-Based Anatomy, Re-Traced was one of the more compelling statements I’ve heard as far as you just re-examining some of the tunes on Traced in Air. Did you make that because you had some regrets or misgivings about how some of Traced in Air came about? Did you feel like there was unfinished business?

PM: No, the reality is that we had a month off between tours and we were like ‘what’s the most productive use of this month?’ And we’re like ‘well, we know this record inside out. We’ve been touring it for a few years. Let’s show people where the songs come from.’ At first it was going to be a bare-bones acoustic kind of reinterpretation. But then when we got in there and started messing with them, only one of the songs did that and the other three became kind of acoustic/vocal experiments that we could build on. Sean started doing interesting drum stuff and the songs took on a life of their own so it became this really fun, productive month. It was really just a means of staying creative, staying in the process, and keeping things moving.

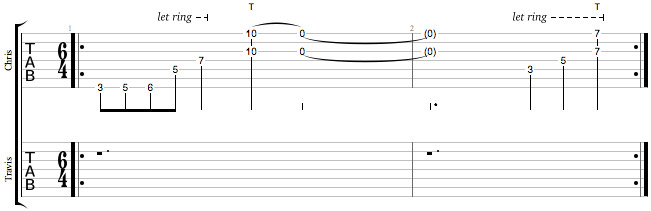

LD: What’s your guitar rig like?

PM: I have just an Axe-Fx [Ultra, by Fractal Audio] with my good old trusty Steinbergers and a million and one patches. There’re so many sounds going on.

LD: The new album is so huge. Is it a challenge to pull it off live?

PM: It’s definitely deconstructed to some degree because you can’t do twelve guitar parts, but I think it captures it. The live thing is a different animal, but it’s fun. You go to this extreme and then of course you fantasize about doing a really simple thing. There’s just a lot of components to playing such complex layered stuff where you just kind of go ‘man, I just want a simple rig.’ Just half of rehearsing for a tour is learning your pedal board. We just have an old [Voodoo Lab] Ground Control, but it’s constant patch changing, from clean to dirty to this sound.

On some songs it’s kind of ridiculous and sometimes I wonder ‘does it make a difference really? Do I need to do that specific sound and add that little extra block that’s going to add that tiny little bit of flanger?’ [laughs] But I don’t know, I guess we’re kind of sound geeks and we’re really into it. 90% of these PAs don’t even capture that amount of detail, but for us guitar geeks it matters, right? We’re paying attention.

IC: What are some of the amp models and cab models that you use?

PM: I’ve got a bunch of Bogners and Buddhas in terms of impulses of cabs. It’s a lot of blocks of drives, overdrives, amps, a very sparse use of each kind of thing. They’re all packed, my CPU is maxed on most of my patches. You can get into such precise detail. It’s kind of endless, but I love that about it because if you know what you’re looking for, it’s there. It’s just a matter of how patient you are with it.

LD: Was there material that you wanted to put on the EP that didn’t make the cut?

PM: Well, we were working on a full-length and all the tunes were picked for the full-length and the manager was like ‘looks like this isn’t going to come out until 2012 based on what’s going on. Do you have anything else you can get out there right now that we can do to keep things moving and to get out and tour?’ and I was like ‘let me look.’ Sean and I got in the room and I had a bunch of things that I thought were interesting that weren’t going to be on the album. I turned it in and in 6 weeks we did this thing. I was so excited because it was so concentrated that there is a lot of improvisation that happened. It was just a lot of free moments that became concrete parts of the composition but it was just totally improvised in the rehearsal room. It’s kind of cool when that happens.

LD: So none of this is off the full-length that you’re working towards?

PM: Oh no, totally different stuff.

LD: How does it compare? Is it part of the same spectrum?

PM: It’s hard to say right now ‘cause it’s still in a very early stage as these demos, but in some ways it’s more proggy. This was more kind of an ambient soundscape, abstract feeling kind of thing and the new stuff’s kind of more literal. Once you start getting into the production side of it, it has a life of it’s own and it sounds completely different than where it’s at now, so it’s too soon to say at the moment. But I’m really excited about where it’s at right now in terms of the arc and the feeling of the album. This is going to be really interesting.

[Special thanks to Devin Kumar for his fantastic video work, Jerome of chapter9photography.com for his outstanding cover photo, and Ian Fleming for lending us his camera gear.]