Mikael Åkerfeldt doesn’t growl at all on Opeth’s new album Heritage. One could assume he left that duty to his diehard fans who still bemoan the titular sea change of 2008’s Watershed; while several songs sparked a familiar din, they were largely drowned out to faithful ears by the dabbling of female duets and piano-led balladry. But in brash assertion of that album’s bold explorations, Heritage further distances the band from their death metal roots. The album is less a recitation of their extreme Pixies-prescribed ‘loud-quiet-loud’ and more ‘piano-overdrive-flute.’ If Watershed was the sound of a revered metal band edging into lush new terrain, then Heritage finds them running wild through the garden with little regard for their fans’ aversions to more floral hues.

Devouts be not dissuaded, however. Heritage is a rewarding narrative that takes several spins to fully ripen in the ear. While some fans many not have the initial patience, they should remember that for a band that has trafficked compositions with double-digit track lengths, Opeth have never been for the impatient.

The album begins with the title track, a stirring solo piano reflection that contemplates Erik Satie, much in the way the Agalloch’s Marrow of the Spirit whispered in the thunder with solo cello last year. Five albums ago this intro would have been the ominous calm before a sudden quake, but here it is allowed to unwind and recapitulate with poetic grace. Only then does ‘The Devil’s Orchard’ break in to introduce the new boss, not quite the same as the old boss. Their sinewy riffage remains, though unison lines have been traded for a frantic interplay that recalls the gymnastics of Rush. Even the production alone is fair warning that these guys ain’t playing around in Blackwater Park no more.

Harsh distortion has been replaced by warm tube-saturated overdrive. Chord clusters of razor abrasion are swapped out to make way for Steven Wilson’s spacious mix. And while six-string disciples may cry foul, herein lies the rub of Heritage, if not the caress: Opeth has pruned back the vertical to allow a wider pan on the horizontal; by compressing their extreme vacillations from brooding acoustics to cacophonous howls, the band clears out the brush for a menagerie of sounds to grow out the sides.

No song boasts a wilder world sound than ‘Famine.’ The first minute welcomes a parade of flute, white noise, and Afro-Cuban drumming before the song’s main piano interrupts. By the end of the song a sludge flood rolls beneath another flute solo like Black Sabbath offering up Ian Anderson as sacrifice.

‘I Feel the Dark’ glides through the first half of its six-minute length, taunting the listener with low volumes before the trademark volume spike that helped define Opeth’s sound. But rather than feel like a left field ambush, it’s a violent exhale from bated breath, coughing forth proggy breaks. This respiratory cycle is the album’s most concise display of the Opeth’s new dynamic treatment: the loud is unison and relentless, while the quiet is sprawling and poignant.

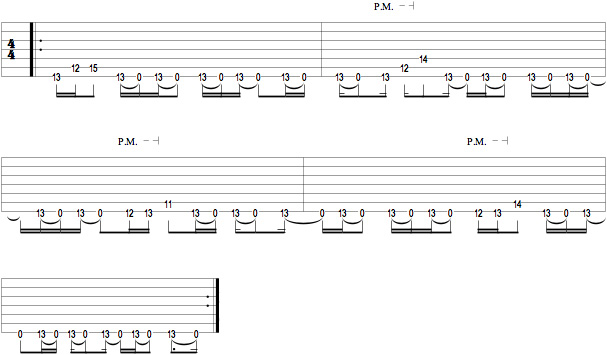

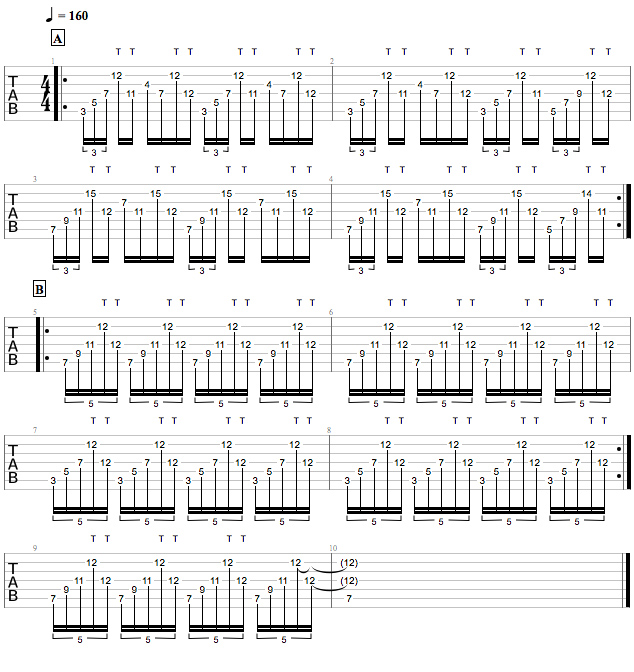

‘Slither’ stands as the band’s most accessible track to date, a burly rocker that tears down the road and off a cliff like a Harley-riding Wile E. Coyote refusing to look down. It’s an unabashed embrace of classic 70’s rock, wearing the hues Deep Purple like a badge and not a bruise. Åkerfeldt still makes it clear who’s driving with his trademark incorporation of open-string dissonance with fretted trills.

Admittedly a first listen of Heritage could be underwhelming; the music is bloated but not heavy, meandering but not transporting. One would hope that if Åkerfeldt insisted on keeping the metal lyrics, he would at least retain the metal growl. A maudlin refrain like ‘God is Dead!’ doesn’t have the same menacing resonance when emanating from his velvet pipes. He really can’t be faulted though, as he’s elevated his singing to truly transcendent heights. His vocals can now dig into grit, as well as slide to falsetto with an effortless command. With such bluesy and soulful inflections now at his disposal, a growl would be a knuckle-dragging de-evolution.

Lest the listener decry for once and all that Opeth have lost their way, consider that while Åkerfeldt has always held skilled musicians in his company, never before has he had them show so many different faces. Martin Axenrot’s drums snap and splash with jazzy abandon on ‘Haxprocess’ and cut and wash over the brush breaks of ‘Nepenthe.’ Martin Mendez’s bass runs with wooly fervor in counterpoint to the guitar lines of ‘The Lines In My Hand,’ but quietly buoys the piano in the title track.

And while the keys of Per Wiberg lash in unison on ‘Slither,’ they recall Yann Tiersen-esque respite in the middle of ‘Folklore.’ The assembled musicians all make versatile use of their craft, each of them a priceless cog and valve to a curious machine. The result is both a challenge and testament to Åkerfeldt’s blueprints and just how many times he can reinvent his own wheel.

Upon the release of 2003’s Damnation (their true watershed album), Åkerfeldt disclosed in interviews that the band had finally made the album he’d wanted to release since he was nineteen. Since then each successive album has seemed to shave off some of Opeth’s core constituency. But with Heritage they unchain themselves from their rabid fan base altogether. Those who might hope that the album’s title referred them getting back to the Orchid days will be sorely disappointed. The title seems to refer rather to Åkerfeldt’s long professed affinity for classic and prog-rock like Deep Purple and Camel.

In Greek mythology, Procrustes was a cruel son of Poseidon who would invite weary travelers into his home and offer them a bed. If the guest were too short for the bed, Procrustes would stretch them on an iron rack until they fit, and if too tall he would amputate the excess length. As brutally metal as the myth may be, the backlash to an aged metal band’s new release often feels like the bed of Procrustes: new forays are either torn too far from their roots or come up short in offering anything new.

Indeed few genres inflict such growing pains as the metal community imposes upon its idols. As an artist’s youthful angst gives way to a meditative maturity, visceral aggression wanes with the waxing of new creative phases. Sadly the same cannot often be said for their consumers who will invariably pine for the ‘glory days’ with myopic hindsight and don’t always grow up looking over the same horizons that their heroes do.

Perhaps Heritage could most honestly be judged by its cover. Making an unprecedented use of the full color spectrum, Travis Smith’s artwork evokes a Bosch-ian treatment of the band’s two-decade legacy. The band’s faces grow from the boughs of a tree in whose roots sits a Janus-faced devil figure pointing in both directions. In the background lies a city in flames from where a procession of people come to draw fruit from the aforementioned tree.

The devil underground literally references their black metal roots; the Orchid days that saw a young band looking back as well as forward in the lineage of metal music. From this origin has sprung the band in its modern, more verdant incarnation. The burning city is their legacy, razed and far behind them. From the flames emerge common folk (perhaps their original fans now twenty years wiser?) to snack on their newly born fruit.

While diehard fans might still rather prefer taking a spiteful bite from Åkerfeldt’s face, the metal community at least owes them a more measured listen. From the beginning, Opeth has made no bones about making progressive music, so the only way they could truly disappoint would be if they ceased to progress. Heritage is the sound of a band reaching full maturity, reaching back into the soil that bore it before outgrowing their roots. And while the black clad congress might not want to eat their vegetables, the nutrients of Heritage may be just what the doctor ordered.