Welcome back to Beyond Theory and to what already is column #5! Today we will be talking about Hindu Rhythms as applied by Oliver Messiaen (1908-1992) in his composition titled Canteyodjaya (Solo Piano) – as well as going over a few other compositional techniques employed in this study. This work amounts to what is essentially a short (ca. 12 minutes) piece on Hindu rhythms, which Messiaen finished composing while visiting Tanglewood, MA in August 1949 (and not 1948 – as most sources state).

You will notice that Messiaen will use authentic names for each rhythm in the piece, meaning he will label each rhythmic cell that is being used in a given moment. Messiaen himself (in his book: Technique de Mon Langage Musical) states that he got the names and the rhythmic cells themselves from 13th century Hindu theorist Carngadeva – who produced a table with 120 Hindu rhythms (or Deci-talas).

Here are the names of the rhythmic cells that Messiaen uses in this study (in order of appearance):

- Canteyodjaya (the title of the piece – this motive works as the center of the piece, which is constantly repeated throughout the duration work.)

- Djaya

- Ragarhanaki

- Alba

- Lakskmica

- Doubleaflorealila (which is labeled 1st refrain)

- Mousika (which is labeled 2nd refrain)

- Trianguillonouarki (which is labeled 3rd refrain)

Messiaen now initiates what he calls a 1st Couplet, which includes the following:

- Plisseghoucorbelina

- Boucleadjayaki

- Globouladjhamapa (which seem to include the following inside it: Gajajhampa, Simhavikrama, Candrakala, and Ragavardhana.

Followed by a 2nd Couplet:

- Soufflina

- Lineacourbarasa

- Piccoulaneki

- Collinalaya

- Pratapacekhara

Finally, a 3rd and last Couplet (which includes a short 6-part canon):

- Colonnoulevalaghou

- Grenoudita

- Statoua

- Loudjea

- Potanciagourou

- Sedia

For the sake of time, I will only be showing a few of these Hindu Rhythms. Here are some of the ones I find to be most interesting, both as an actual rhythmic figure, as well as Messiaen’s approach in harmonizing and texturing these said figures.

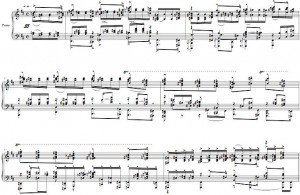

Canteyodjaya – this is the heart of the work, what essentially amounts to the main theme of the piece. This is in essence a 13/16 bar – one subdivision used here is: 3+2+2+2+4.

1

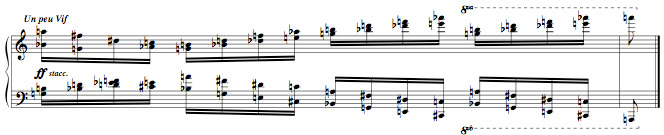

Ragarhanaki – Messiaen creates a thick texture of chords, they take the same rhythmic figure in both hands and in fact must be played with hands overlapping. A measure of 14/16 is followed by a measure of 34/32 – subdivided as: 2+3+5+4 (16ths) and 4+7+13+10 (32nds). Notice how dense the chords are – there are only 3 chords in these two measures. Essentially 7 note chords stacked in a variety of intervallic relations, the predominant ones being that of major seconds and minor seconds. The 2nd measure is in reality an additive version of the first, the same material being held for a longer duration.

2

Mousika – This figure represents the 2nd refrain, a quick right hand figure that leads way to a high cluster, followed by a very low chord at the depths of the keyboard. Finally, another very high, rather open sounding chord with both hands is sounded. The refrains serve to balance the form of the work, by switching the importance from the Canteyodjaya theme to this new material that is given weight in the latter parts of the piece.

3

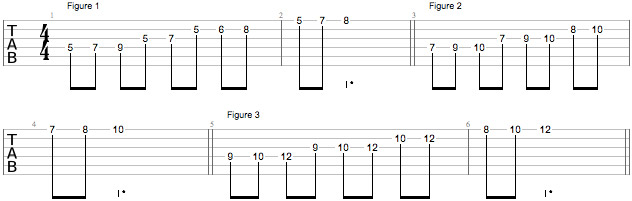

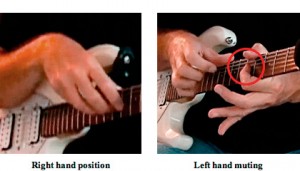

Boucleadjayaki – This figure shows a device Messiaen uses throughout this work as well as throughout his entire compositional career – Parallel motion and parallel harmonization. Though the figure is not harmonized exactly at a single interval relation, the figure still follows the other close enough to allow us to follow it as a form of parallelism. Notice in the other examples given so far, that Messiaen definitely thinks of parallel motion when harmonizing lines and creating chords. The rhythmic figure here is rather simple, five groups of 32nd notes, which form a line of 20/32nds (4+4+4+4+4).

4

Soufflina – a fast arpeggiated figure starts the 2nd Couplet, this figure subdivides into: 8 32nds+ 6 32nds within its first bar, and then has an even faster 32nd note sextuplet in the right hand which leads to long note (taking 3/8). Messiaen seems to be creating more virtuosi type lines, which include long arpeggios and fast gestures as the piece moves along.

5

Notice the sheer amount of material Messiaen inserts into this work! Instead of working off of a few motives and developing them through more common western music techniques, Messiaen instead creates a work in which he superimposes multiple elements – seemingly endlessly. The form of the work is thus organized through repetition and superimposition of its sections, which are given more or less of an aural importance by how many times each section is repeated and where in the work said repetitions occur.

Both the material that is repeated the most (the Canteyodjaya theme) and the material that is not repeated at all (the Couplets) thus help to stabilize the form of the work. We hear the Canteyodjaya theme as important because of its constant repetition, signaling it as the main cell of the work… we also hear the Refrains and Couplets as transitions to a new section of the work, as they serve to break away from the material that gets repeated and superimposed – which we already know well by the time this new section is introduced.

These 2 main sections are:

- The Canteyodjaya – which gets repeated 6 times within the first 8 pages of the work – against material (which is comprised of other Hindu rhythms) introduced around it.

- The Refrains (which do get repeated) and Couplets (which appear only once each).

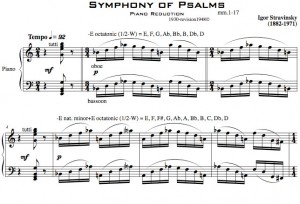

Another moment of importance and what essentially acts as a 3rd element within the work deals with what Messiaen calls, “Mode de Durees, de Hauters, et d’Intensites” – essentially this translates into: Modes of Duration, Pitch and Intensity. The reason this is important is it looks forward to a future work of Messiaen’s: Mode de Valeurs et d’Intensites – from the Four Rhythmic Studies – which were completed shortly after Canteyodjaya.

That work deals with a quasi-form of total serialization, essentially meaning that every aspect of the work: rhythm, dynamics, and pitches are organized and applied through dodecaphonic compositional techniques – though in the case of Messiaen, actual dodecaphonic techniques were of no importance when composing (Look at Pierre Boulez’s Structures Ia for a truly serial work that has been “totally serialized). These sections appear to create a change in atmosphere and texture within the work, and essentially further diversify the thematic material of the piece.

This 3rd element appears three times, and is labeled as following:

- Mode de Durees, de Hauters et d’Intensites

- Gamme Chromatique des Durees, Droite et Retrograde – which happens twice, though the second time the material is truncated.

Let me attempt to decipher this for you, so that we have a method of how Messiaen might have put together a section like this. In doing so, you could apply the same approach, or better yet, a similar approach in your own work. Lets break down the first entrance labeled Gamme Chromatique des Durees, Droite et Retrograde:

The top staff (treble through out these measures) takes the retrograded rhythmic figure, what essentially amounts to the bottom staff (bass clef) figure backwards. Notice both top and bottom clefs have 23 durations. If you were to analyze these durations you would notice that they are actually the same – one going from 1-23, the other starting on 23 and going down to 1.

Notice that while the top clef is slowing down as this section progresses, the bottom clef is actually speeding up. Essentially, both passages are handling the same rhythmic material in the same way, though one is the exact opposite of the other – the top line is essentially going through a process of adding durations, where as the bottom line is having its values slowly subtracted. In short, the retrograde starts with one 32nd and adds another 32nd every time. Awhile the bottom line starts with slowest permutation (half+8th+16th+32nd) – and subtracts one 32nd every time.

Let’s look at the top line, and how Messiaen dealt with pitch:

Essentially, Messiaen is dealing with a simply 7 note figure, which contains only 5 notes. This figure gets repeated 3 times in full, and it gets truncated while in the 4th repeat. Messiaen though, like stated above, never keeps the rhythmic figure the same – the additive rhythmic process means that the 7 note sequence takes longer and longer each time it is repeated.

In Integer Notation (which means to label pitches as numbers, from 0-11 – 0 being C natural) the 7 note figure is the following: [3,2,1,3,0,1,7] Looking at the bottom clef, you will notice Messiaen manipulates all other notes that remain to complete the chromatic scale. In turn, this entire section is really these processes being applied to the chromatic scale itself.

A perfect segue from this retrogradable rhythm we just looked at in the Gamme Chromatique, in which Messiaen created a section where one rhythmic figure is retrograded against itself, is to look at the Hindu Rhythmic pattern labeled Sedia (which is part of the 3rd Couplet). This falls under what Messiaen calls Non-Retrogradable rhythms – simply put – they are palindromes: rhythms that are the same forwards or backwards – essentially the musical equivalent of the word RACECAR. This bar is what amounts to a 19/16 bar that cannot be retrograded, whether you play it forwards or backwards, the bar will sound rhythmically identical.

6

Another moment of interests occurs within the 3rd couplet, here Messiaen sets up a small 6-part canon on a falling 6-note gesture, marked Staccato Marcato. Notice that the charm of the canon is its ambiguous quality, lines appear out of nowhere – one is never sure where the next line will spring from. Messiaen displaces the canon so the entrances are not obvious to the listener, you simply cannot guess where in the canon you are whilst hearing it.

7

Take a look at how Messiaen closes the work, another interesting passage that deals with parallelism and symmetry. Messiaen takes this fast gesture that both climbs and falls at the same time, the line will reach the depths of the keyboard as well as its upper most range. Messiaen ends the work on the note A natural – 7 octaves apart:

8

If you consider all the material presented in this piece, you will come to realize how rich Messiaen’s language truly is: Hindu rhythms, retrogradable rhythms against themselves at different interval levels, non-retrogradable rhythms (palindromes), canons, etc. To think that this doesn’t even cover a small part of his output’s influences: religion, bird song, color (Messiaen labeled almost all of his harmony via colors), and modes of limited transposition… amongst other things.

Oliver Messiaen (1908-1992)

Messiaen is arguably the most important composer to come out of the second half of the XXth century, having influenced just about every composer that came after him. He was actually the teacher (at the Paris Conservatory) of some of the most influential composers of the later parts of the XXth century: Stockhausen, Xenakis, Boulez amongst them. He was also a prolific writer and theorist, having put together very important treaties on his music, and the techniques that influenced his works. Look for his treatises:

- Traite de Rythme, de Couleur, et d’Ornithologie

- (8 volumes)

- Technique de mon Language Musical

I hope you enjoyed the material covered here. This is maybe the most technical column so far – if you have any questions or further insights yourself, feel free to post at the Guitar Messenger Forum. I hope the material here will inspire you to attempt to branch out of your comfort zone while composing, and realize that anything can influence your music. You can open yourself up to totally fresh ideas if you start to encompass totally new influences into your writing. If you want to further look into Messiaen’s music, take a look at some of the following works:

- Turangalila Symphony

- Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jesus

- Et Exspecto Resurrectionem Mortourum

- Chronochromie

- Poeme pour Mi

- Catalogue d’Oiseaux

- La Tranfiguration De Notre Seigneur

Roberto is currently listening to: Almeida Prado – Cartas Celestes n.01