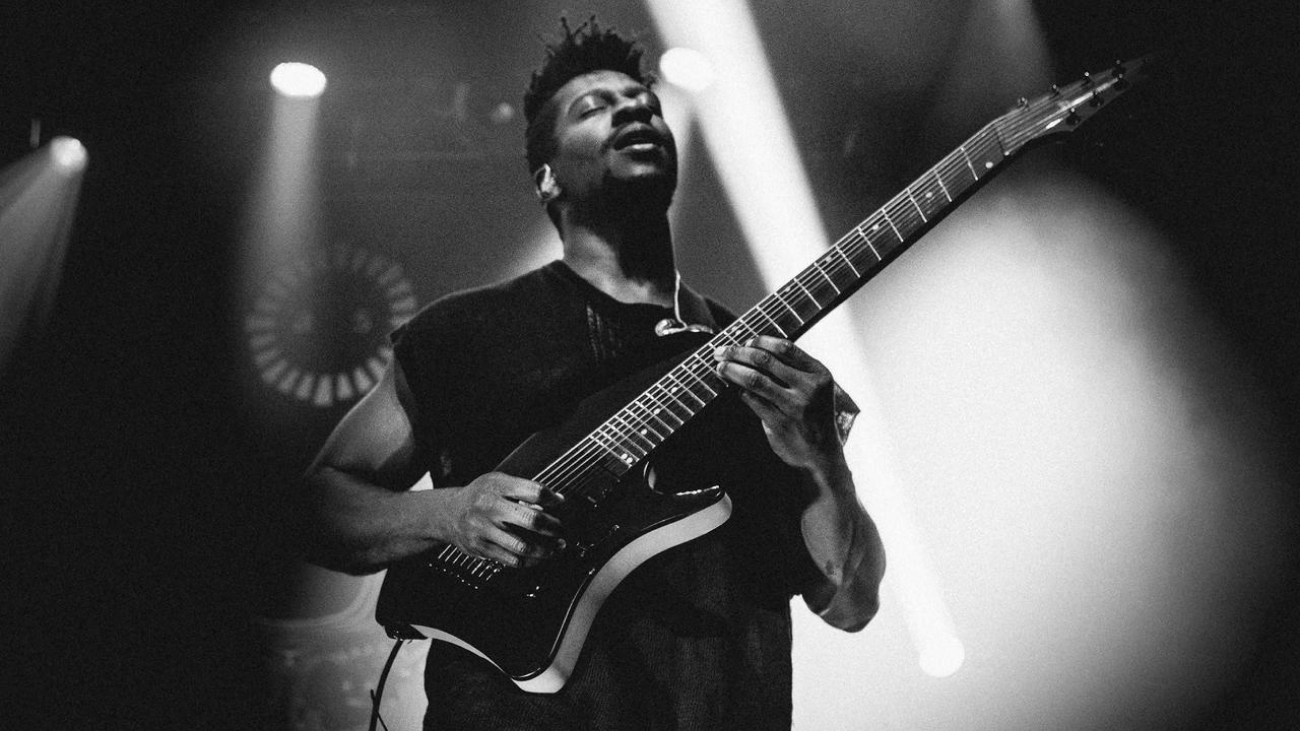

James Byrd is perhaps one of the most underrated guitarists out there today. In fact, Guitar One Magazine named him one of “The 10 Best Guitarists You’ve Never Heard.” However, among those who know him he’s considered one of the most elite players around – one who makes every note count.

James Byrd is perhaps one of the most underrated guitarists out there today. In fact, Guitar One Magazine named him one of “The 10 Best Guitarists You’ve Never Heard.” However, among those who know him he’s considered one of the most elite players around – one who makes every note count.

He describes his style as Symphonic Metal for the New Age, in which he focuses much more on composition for the entire band – or orchestra for that matter – rather than having all other instruments play around lead guitar parts, which is a common trait within the guitar virtuoso community. Byrd is definitely an artist to check out – he’s got a new release coming out in early 2007 and until then you can listen to albums such as Anthem and Flying Beyond The 9 and his band Atlantis Rising.

IC: Can you tell us about your current projects? Any tours coming up?

JB: I’m working on a new album, which I anticipate will be finished in the spring of 2007. I took a lengthy break from writing and recording after my Father passed away in October of 2004, and just concentrated on my guitar company, which of course I am also currently working on.

IC: How did you get started with playing the guitar?

JB: It’s hard to put an exact date on anything other than the day I got serious about it, which was September 18th 1970; the day Jimi Hendrix died. Prior to that, I had always had a guitar, but it wasn’t a serious thing to me. I remember when I was only two or three years old, my older Sister got a guitar for Christmas, and I got one of those little Mickey Mouse guitars with the four plastic strings and the little hand crank which played music. I remember throwing a bit of a fit and wanting the real guitar my Sister got. But up until September 18th, I just knew a couple of chords on the guitar and didn’t put much time into it.

I had never seen or heard Hendrix until the day he died, and when they showed him on the news playing The Star Spangled Banner at Woodstock, that was it for me. I grew up on a college campus during the 60’s and my much older Brother (16 years older) was in Vietnam. My parents were bitterly divided over the war. The reaction of both of them to Hendrix on the news that night was negative in the extreme; it really upset both of them. Being the rebellious type I was, I saw what Hendrix was doing as having a great power in it. They say good art has to upset someone. I saw what I considered great art that day, and knew from that moment that I’d pursue the guitar.

IC: Who would you say are your greatest influences both for guitar playing and composing?

JB: There were distinct phases. My earliest and two most important influences were Ritchie Blackmore, and Jimi Hendrix. My infatuation with Hendrix lead me to want to understand his music better, so I began listening to the blues guitarists who’d influenced him. I immersed myself in the blues for several years. My first ambition in terms of technique was to develop a great vibrato and phrasing. I learned almost all of B.B. King’s classic solos and also some songs by Hubert Sumlin. I also loved Paul Kossoff of Free because he had a great vibrato. I hate to toot my own horn, but by the time I was 15, I had as mature a vibrato as Paul Kossoff and could draw crowds in music stores with the first note.

JB: There were distinct phases. My earliest and two most important influences were Ritchie Blackmore, and Jimi Hendrix. My infatuation with Hendrix lead me to want to understand his music better, so I began listening to the blues guitarists who’d influenced him. I immersed myself in the blues for several years. My first ambition in terms of technique was to develop a great vibrato and phrasing. I learned almost all of B.B. King’s classic solos and also some songs by Hubert Sumlin. I also loved Paul Kossoff of Free because he had a great vibrato. I hate to toot my own horn, but by the time I was 15, I had as mature a vibrato as Paul Kossoff and could draw crowds in music stores with the first note.

My Blackmore infatuation led me to an interest in classical music and 1930’s jazz especially D’Jango. That influence lead to more progressive things in my late teens, and I briefly delved into what was called “fusion” at the time, especially Al DiMiola. Frank Marino was also an inspiration, especially to play very fast and with a lot of intensity. I remember sitting around with the Mahogany Rush Live album and playing along note for note with his solos. I listened to a lot of different players of different styles and learned from them in the 70’s.

IC: While there’s still plenty of virtuoso guitar-playing throughout your work, you seem to also leave a lot of room for the music to breathe. What kinds of things do you look for when creating a balance within the song?

JB: You know, I don’t think about it too much. I never consciously think “I have to start out low and slow and build up” or “make this shorter”. I just play what comes to me naturally. I almost never listen to so-called “shred” guitarists or instrumental techno-fests; I like melodies. Great solos have to be well played, and memorable.

IC: I really enjoyed to listening to one of your classical works – ‘Avianti Suite Op.1 No.63’ off the Flying Beyond the 9 album. Do you ever plan on recording a full concerto?

JB: Thank you. I’d love to, but the budget is way out of my reach in terms of using a real orchestra.

IC: How did you go about learning how to compose and arrange classical music for a full orchestra?

JB: Well, first, what you’re hearing is not a real orchestra; it’s approximately 60 tracks of samples painstaking put together by me. But I did follow a composer’s template in that undertaking for each instrument, I knew the range and function, and composed the parts accordingly. This isn’t something I formally learned, it was just something I undertook on my own. Except for the Harpsichord part, nothing was scored. I just heard the finished music in my head, and recorded each layer that made it up according to my composer’s chart of instrument ranges.

IC: You are perhaps the only guitarist in the neoclassical-metal genre who has been supported and endorsed by Yngwie Malmsteen. What are your thoughts on this? How do you feel about his latest work, Unleash the Fury?

James Byrd and Yngwie Malmsteen in 2003

JB: Well, given his stature it’s very flattering. I’m a bit embarrassed to say so, but I haven’t heard it. The last album he sent me was Magnum Opus. I thought that was quite brilliant. A lot of people who don’t know my history as a musician, hear my music and assume Yngwie was a huge influence on me. But really, I’m anything but an expert on him. One of the reasons we became such good friends, is because we have remarkably similar backgrounds musically. We share an almost identical experience regarding Hendrix on September 18th 1970, and we both loved Ritchie Blackmore and Uli Roth. What’s funny is that he doesn’t think I sound like him at all, but he once actually mistook a Tony McAlpine solo for his own.

I recognize our playing similarities more than he does; I was on the phone one night in a three-way call with him with Uli, and we were taking turns playing music we were recording for each other. Yngwie thought I sounded like Uli, and Uli thought I sounded like Yngwie. I think that was one of the more memorable times I had hanging out with other players. Uli was a big influence on me during his Scorpions period; I could hear similarities to both of these guys, but they could only hear the other guy. When Yngwie got Uli on the line it was pretty funny the way he introduced me; “James, I want you to meet Uli, my God and your God” he said. If you listen to Yngwie’s earliest playing like “Black Star”, it’s almost note for note Uli Roth from the Electric Sun albums. I took a lot of stuff from the same albums at the same time.

IC: What kind of gear are you using nowadays? Can you tell us about your custom guitars?

JB: It’s remarkably simple, but also has had a lifetime of effort put into it. I don’t have a rack, or even a pedal board. My guitar goes into a DOD 250 overdrive, an original Dunlop cry baby, and then straight into a 50 watt Marshall plexi I bought in 1996. The amp is stock except for some extra fuses across the mains –it caught on fire once-. It’s not a high-gain amp at all; if you don’t use an overdrive pedal, it stays 90 percent clean at full volume with single coil pickups. The overdrive box has just enough gain to push the amp into power tube distortion with my guitars. I also had the pre-amp wiring re-routed to make the amp a bit quieter, but that’s it. My speaker cabinet is rare; it’s a Marshall model 1990 from 1967. It has 8 original ten-inch 10 watt ¾ inch cooper voice coil alnico Celestians in it. It sounds amazingly better than any 4X12 cabinet, having both more top end and more bass because it’s a huge cabinet. I only use plain carbon batteries in my two pedals, I find this actually makes a real difference to the tone. I use matched Tesla EL84 tubes in the amp.

Byrd ™ Super Avianti ® Guitar

My multi-patented Byrd ™ Super Avianti ® guitars are where my biggest effort went. I’d had endorsements with a slew of companies in the 80’s and early 1990’s. I wanted a guitar that gave me everything a great strat could, but no one had ever really addressed what I had considered to be the annoyances of the Fender over the years. Everyone just assumed it wasn’t up for re-evaluation. I thought it was. I never liked the block neck joint, and I never liked the lower body horn; if you assume the classical position on the upper end of the fret board to play arpeggios, you bang your wrist right into that horn.

I also thought the headstock design was fundamentally backwards in terms of string tension. I used to use left-handed necks on my strats because it made bending the higher strings easier. I had played strats for 99 percent of my time as a guitarist, but the other guitar I had favored was the Flying V. I liked that the upper fingerboard wasn’t occluded by a lower body horn. That was really all I liked about it; the control placement was terrible, and I don’t like shorter scale length guitars. So the beginning of my idea was to build an ultimate guitar, which would marry the three – single pickup array and scale length of the strat, with a new body shape. They are an off-set asymmetrical V shape, but unlike any other asymmetrical V shaped guitar, it’s backwards with the longer body wing being the lower one. This wasn’t done for cosmetics; it was done to balance the guitar’s center of gravity by compensating for the material removed from the control cavity.

The shorter upper wing is also ergonomic. I came on the idea of actually inlaying the entire pickguard assembly into the instrument, instead of just screwing it on top as other manufacturers do, and it uses polished flush screws instead of the usual oval head screws. Everything is dead flush and smooth. It took me several years of experimenting with different pickguard materials and methods of doing the precision inlay before I hit on the final method. The pickguards are made from a material called Acrylite ®, which is a very hard acrylic. They make a big difference in the tone of the instrument actually, giving more definition and spank to the sound. The guitars also feature a sculpted bolt on neck heel that feels as nice as a set neck. I found bolt-on necks to actually have a more lively sound than set necks for a number of reasons too lengthy to go into here. The guitars also feature a patented reverse 2+4 straight-pull head stock design that uses no string trees, and they stay in remarkably good tune without the need for a locking tremolo.

My guitars are also available with my unique UDC fingerboard, a type of scalloping that’s contoured according to where you actually put your fingers rather than just a standard scoop. They also feature 7 way pickup combinations, and noiseless DiMarzio ® Virtual Vintage single coil pickups. I now offer the instruments to the public by custom order, and players can specify their neck size and shape in ten one thousandth of an inch increments and choose from about a dozen different pickup winds. Byrd Super ™ Avianti ® Guitars can be seen and ordered at BYRDGUITARS.COM

IC: What would you say have been the high-points and the low-points throughout your career?

JB: Being chosen by Guitar Magazine as “One of the ten best guitarists” in 1996 was definitely a high point. The low point came early when I had to have major hand surgery in 1989 for tendonitis that was bad beyond steroid injections.

IC: What kind of music do you listen to these days and how do you feel about the overall state of the rock genre today?

IC: What kind of music do you listen to these days and how do you feel about the overall state of the rock genre today?

JB: Short answer is whatever my wife has in the CD player in the car! Other than that, I either listen to the same music that originally moved me, like Deep Purple or Hendrix, or I listen to classical music. I like everything from Blackmore’s night and Paco Delucia, to Debussy and Mozart.

IC: What advice can you give to aspiring musicians here at Berklee?

JB: Learn to play blues well. There’s probably a lot of focus on the intellectual end of music in college, but all the knowledge of theory in the world won’t enable you to communicate your deepest emotions through the instrument to a listener; that is primal and really learning the deep blues will teach you to approach musical phrasing from the perspective of a vocalist; you will learn when to ignore playing in time – rather a lot really.

Far too many guitarists play like they’re practicing to a metronome and it’s just horrid sounding to me. It’s why I don’t listen to all these so-called shred players; it’s usually just a metronomic stream of 32nd notes without phrasing or dynamics. I lose interest after about 15 seconds of that and I think most non-musicians do as well. It’s just not musical or natural sounding. I’d much rather hear David Gilmour. Listen to how great singers handle the phrasing of a basic melody. You can’t go wrong with Sinatra or Ottis Redding; they both understand the art of phrasing.

You have to have something special to really pull off the blues because they’re so simple in terms of notes. But they are not simple to play. Don’t be musically stiff. If you can develop looseness and freedom of feeling, you can add all the modes and knowledge of advanced technique to expand the music and also still reach people emotionally. Record yourself and listen back. If you’re not happy, that’s a good start. You should never be too satisfied because there will always be room to improve. Be self-critical and you’ll prevent others from doing it for you. Finally, strive to be authentic; there will always be someone faster, more advanced, or technically better somewhere. But if you’re authentic (honest) with what you put down, it will always stand out.