The Law of Aging Metal Bands would dictate that Iron Maiden, now in its 35th year, should be long excused from the artistic role call. The paradigm dictates that a handful of their top tunes should be treading water in classic rock playlists as the members themselves retire to a pension of VH1 reality show appearances. Fortunately for us, Iron Maiden is not your average aging metal band.

The Law of Aging Metal Bands would dictate that Iron Maiden, now in its 35th year, should be long excused from the artistic role call. The paradigm dictates that a handful of their top tunes should be treading water in classic rock playlists as the members themselves retire to a pension of VH1 reality show appearances. Fortunately for us, Iron Maiden is not your average aging metal band.

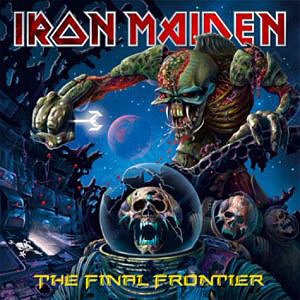

While their fans may be just as happy to see them tour every year with a set of greatest hits from two decades ago, the band continues to release and perform new music. The latest salvo, The Final Frontier, is the band’s 15h release, and with its cover art that looks like a tie-in to the new Starcraft game, this monolithic slab of metal may initially put off the most die hard of Ed Heads. Aggressive bass synth kicks off the opening ‘Station 15…’ and lurches into a King Crimson-esque industrial grind that is disconcertingly alien to the Maiden canon.

But release your grip from your expectations and dig into the new tunes, because after a few spins, you’ll find that the record’s ambitions and departures make for the most rewarding Maiden albums in years. If 2006’s A Matter of Life and Death was a curious misstep, we can now rest assured that it was a Petri dish used to toy with the genetics that have given birth to this beast.

Rest assured, the band is in top form. Bruce Dickinson’s vocal chords seem to be aging like Benjamin Button, the guitar work runs the gamut from creamy taste-tacular to proggy gonzo and all at the right times, and Steve Harris still kicks the bass like a steel-toed humming bird. While the tempos may not be up to the warp speed of the band’s youth, Nico McBrain reigns atop the drum throne as metal’s most swinging drummer, running laps across his kit with a punishingly classy swagger.

And yet with this release, so much of what has defined Maiden’s iconic sound has been pushed from the foreground. Since Dickinson’s prodigal return to the ranks in 1999, the band has mined a holy guitar trinity to its full potential, when six-string Maiden mainstays Dave Murray and Adrian Smith were joined by Dickinson’s solo guitarist Janik Gers. Whereas in recent outings this arrangement allowed an extra guitar to double the bass and bolster Maiden’s trademark guitarmony lines, lead harmonies are now few and far between. When they are employed, they swim through the lower registers like copulating sea serpents or sustain themselves beneath a chorus refrain.

But while the purist may call fie, the orchestration results in undeniably heavier riffage. Just check out the main parts to the album’s ballad, ‘Coming Home,’ a spiritual soundtrack to last year’s Flight 666 tour documentary. Steve Harris, metal’s most audible bassist, may have lost his overbearing presence in the mix during the album’s heavier moments, but it’s for a good cause (and this is coming from a bass player, mind you). Where his punky P-bass gallop used to be a low-end cudgel, it’s now the sturdy spine of the meaty grooves – though he still gets his raunchy trot on in the good time sing-along ‘El Dorado.’

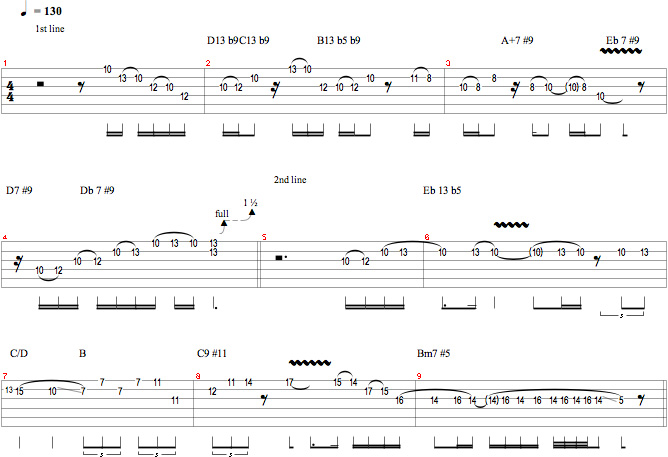

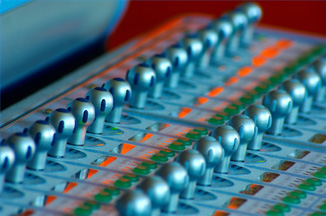

By downplaying harmonic acrobatics, Harris and Co. let the composition and the production of the album shine through. Having manned the mixing board since Dickinson returned, producer Kevin Shirley has finally found the perfect balance of raw rock fury for rhythm parts and cutting tones for leads. The title track displays sound craft at its best as it carves a whole song out of what is essentially one riff taken through a gauntlet of dynamics and attacks. Never settling for aural homogeneity, under-dubbed acoustic guitars float a cocktail of contrasting chord voicings and electric tones, and while the often polarizing use of strings still pervades much of the album’s midsection, it never crescendos to offending volumes but rather lies deep in the mix like bedrock.

The songs themselves represent another departure from what we’ve come to expect from the architects of NWOBHM. Steve Harris has gotten more use out of the b6 –b7 – 1 progression than MacGyver ever could with a Swiss army knife, but here he eschews its use for a broader harmonic horizon that results in the band’s most complex work to date. They even seem aware of it themselves as the track order seems to wean us away from our Maiden comfort zone, the first three tracks standing strongly with the best of their 21st century work. ‘The Alchemist,’ the album’s shortest track (perhaps due to the fact that it’s also the most uptempo), harkens back to the epic bombast of the Powerslave album.

But it isn’t until Harris lays into an odd metered groove midway through ‘Isle of Avalon’ to set up a prog rock party that the discerning listener realizes how much of a cornerstone this album really is for the band. The last song, ‘When the Wild Wind Blows,’ clocks in at just over eleven minutes making it the third longest in the band’s catalog, and as they tear into the final climactic riff, I defy you to say it is not one of their finest. The lyrics spin a modern Twilight Zone yarn while the riffs build with fittingly apocalyptic bravado – laying waste to any lingering doubts about Maiden’s prowess.

Make no mistake: this album is not for the impatient. The final three tracks all clock in at over eight minutes, each crawling from a clean, meditative intro to a trampling finale. But with such an assembly of pristine production, flawless execution, and some truly epic lyrical treatments, the album can only be criticized for commanding the listener’s full rapt attention.

In recent interviews, the band assures that they by no means intend this to be their last studio outing. While there isn’t a central lyrical theme running through the whole album, there is a sense of reflection on their long and storied careers- but the boys have celebrated their longevity by furthering their art. So many over-the-hill bands spend their later years as a wrinkled tribute act to their glory years, and yet Iron Maiden continues to grow. Here’s to hoping that this is not a final frontier, but a new one.