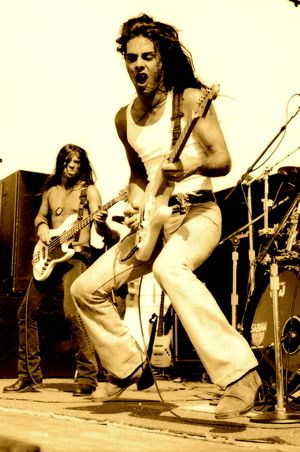

Richie Kotzen is one of today’s most intriguing guitarists. He arrived on the music scene in the late 80’s through Mike Varney’s Shrapnel Records and became one of the leaders of the shred revolution of the time. After breaking through as a guitarist, his musical focus has shifted more onto songwriting – though he’s still had time to incorporate jazz/fusion influences into his tasteful blend of rock and blues guitar. Without compromising for the standard of virtuoso playing that put him on the map in the first place, over the years Richie has established himself as a soulful singer and songwriter, and developed into a full-fledged artist with a supportive fan base worldwide.

Richie Kotzen is one of today’s most intriguing guitarists. He arrived on the music scene in the late 80’s through Mike Varney’s Shrapnel Records and became one of the leaders of the shred revolution of the time. After breaking through as a guitarist, his musical focus has shifted more onto songwriting – though he’s still had time to incorporate jazz/fusion influences into his tasteful blend of rock and blues guitar. Without compromising for the standard of virtuoso playing that put him on the map in the first place, over the years Richie has established himself as a soulful singer and songwriter, and developed into a full-fledged artist with a supportive fan base worldwide.

IC: 2008 seems to be a pretty busy year for you so far. So what are you up to at the moment?

RK: Yeah. Well, what’s new? I’ve got the live record [Live In Sao Paulo] that I just released, and there’s a DVD that goes with it. It’s the first real live record that I’ve had. There are some DVDs that I’ve put out, but they were sorta homemade – just for the hardcore fans. But this is a pretty cool show that we did down in Sao Paulo, and we had the opportunity to have the cameras there, and have the Pro Tools there to record everything the right way. So it came out pretty well.

IC: What are your plans for the rest of the year?

RK: Well, I’m going to do some things in New York this weekend: in-store, and a couple of radio things to promote the record. Then I leave on the tenth of July for a month and a half, because I’m going to be touring all through Italy and some other parts of Europe. The first half of my tour is going to be with the band, and we’ve got about 13 shows booked with the three of us. Then those guys go home, and I stay over there and do a run of acoustic shows by myself, which should be kind of fun. I’ve actually done that before – a couple of years ago I went to Spain, and did like seven shows and drove around the country and did these little acoustic gigs. It was a lot of fun.

IC: I imagine it would give people a different perspective of your music. Do you still get to put in all of the guitar work when you do the acoustic shows?

RK: Yeah, it’s not really about that. I mean, it’s me playing my songs. My fan base that has been coming to my shows, especially in Europe, they know what to expect from me. It’s interesting, because I think still in the United States, when people hear my name who don’t really know what my records sound like over the last ten years, they really equate me to the crazy guitar-playing aspect of things, which I can still do – I can still play (laughs).

But over the years, I really came to the realization that the reason I learned to play the guitar was to be creative and create music, so that’s been my focus over probably more than ten years. Since my second or third record, it’s been more about just expressing the music, and if there’s a spot for the guitar to do something that’s a little unique, then it happens naturally – rather than in the old days. When I was a teenager, I wanted to throw every possible thing I knew out there, because it was all fresh to me, and I felt like I had to make a statement with the guitar. But now it’s more about the songs that I write and the music – recording it and being creative that way.

IC: Over the course of your career you’ve been involved in over 50 albums, including solo releases, band releases, and other collaborations. What inspires you to stay this productive over the years? How has this changed since you started in the late 80’s to your more recent releases?

RK: Well, you know, I think what has happened is that… it’s something that’s looked at over a long period of time. My first record was put out in 1989 – I was 18 when I made that record. So now I’m 38. Over that timeframe, a lot of things happened. I think I was averaging maybe a solo record a year. Then there was a couple years where I didn’t do solo records, and that’s when I was doing bigger band things. I think it’s just time. I don’t think I’m some guy who writes songs all day long, because I’m really not. As a matter of fact, I don’t really write the song unless it writes itself. In other words, if an idea comes to me and it comes naturally and it develops into a song, then great.

RK: Well, you know, I think what has happened is that… it’s something that’s looked at over a long period of time. My first record was put out in 1989 – I was 18 when I made that record. So now I’m 38. Over that timeframe, a lot of things happened. I think I was averaging maybe a solo record a year. Then there was a couple years where I didn’t do solo records, and that’s when I was doing bigger band things. I think it’s just time. I don’t think I’m some guy who writes songs all day long, because I’m really not. As a matter of fact, I don’t really write the song unless it writes itself. In other words, if an idea comes to me and it comes naturally and it develops into a song, then great.

But the thing I think a lot of writers get into trouble with, is they’ll sit down with an idea: ‘I’m going to write a song.’ And then they write maybe one part of it, and they try to force the rest, and then it just weakens the creative process. The answer for that is just to allow things to happen, and if nothing’s coming, then don’t write anything, because it’s not meant to be written. And what happens is that I’ll go months without writing a song – months! And then all of a sudden, in three weeks I’ll pop out two or three really honest pieces of work that I think are worth recording. So it’s kind of a weird cycle.

IC: Yeah, but you’ve definitely kept up that pace over the years. In 2007 you had a new studio album and now, in 2008, a new live record. Which release out of all of the albums that you’ve put out are you most proud of?

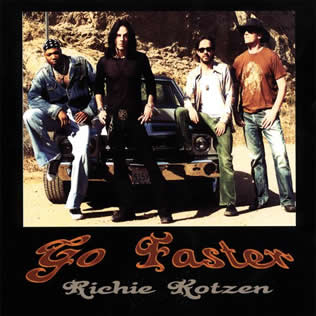

RK: Kind of moments on all of those records. There are certain moments that I like – certain songs. Off of the new record, Go Faster, I really like the song ‘Fooled Again.’ I like the way that turned out. I kinda had an idea for that song – what I wanted it to sound like after it was written, and I think I accomplished that. I think it just came out the way I envisioned it. I like the live record a lot, and especially the video that goes with it, because it really shows what I’m about. A lot of times with a studio record, you have a lot of choices to make, and the choices you make color the end result. Whether it’s a guitar overdub, or a tambourine overdub – whatever it is, you have that luxury. But with the live record, there’s only three of us on the stage. So it’s really kind of raw, but it really works, because you’re hearing the true essence of what I do, and what I’m capable of, and what my limitations are and all that stuff. And I think for anyone that’s interested in my music, I think that’s probably the ultimate record, because it’s the most honest.

IC: What have been some of high and low points of your career so far?

RK: I think the low points in a career… and I can only talk about my career, I can’t talk about anybody else’s career. So this isn’t me saying this is how it is; this is how it is for me. I think the worst parts for me were anytime that I was doing something because I was expecting a result other than just finishing the song creatively the way I hear it, I would get myself in trouble. And what I mean by that is… there was a period where I had a major record deal with Geffen, and I pretty much did whatever I wanted on that record. That record was completely true to the creativity of the time, so on that level it was great. On the commercial level, it didn’t get promoted at all. As a matter of fact, when I finished the record and took it to the label, the guy that signed me wasn’t even gonna be staying at company, so they were just like: ‘Well, we’re not gonna push this, because this guy’s leaving, and whatever’s happening here is happening, and it’s not going in the direction that likes what you’re doing.’

So there was that business element that was kind of frustrating, because here I thought that I did something that was really great, as far as what I wanted to do, and it wasn’t really gonna see that light of day. So that was kinda frustrating. Then somehow in Japan they go a hold of it and decided they really loved it and they wanted to promote it, and they sent me over there, and that’s how things started happening for me in Japan, which eventually translated back to here and over to Europe. And now my career is probably better than it’s ever been, because I’m able to tour more countries and go around the world every year, and do all these things and make the records I want to make.

So there was that business element that was kind of frustrating, because here I thought that I did something that was really great, as far as what I wanted to do, and it wasn’t really gonna see that light of day. So that was kinda frustrating. Then somehow in Japan they go a hold of it and decided they really loved it and they wanted to promote it, and they sent me over there, and that’s how things started happening for me in Japan, which eventually translated back to here and over to Europe. And now my career is probably better than it’s ever been, because I’m able to tour more countries and go around the world every year, and do all these things and make the records I want to make.

But the real answer to the question is: I think anytime you get involved in a situation where you have expectations that relate to things that you don’t have control of, you set yourself up for a problem. That’s what I learned. The thing that I concern myself with is making music that’s true to me, and that’s what I do. And the thing that’s really great – the fact that all these record labels are in trouble is brilliant for someone like me, who has a fan base that’s maybe small enough that a major label isn’t gonna get involved in, but it’s big enough that I can facilitate and get the music to those people. I don’t really need to be on a record label. So that’s a great thing, because now what I’m able to do is completely eliminate the uncreative process of making music; which is dealing with executives at record companies. That’s the ugly part, because they’re not creative people. They think they are, but they’re not. They have opinions, and that’s the end of it. So to be able to eliminate that aspect, and to be able to exist solely as a music maker – I’ve reached the ultimate nirvana, so to speak. (laughs)

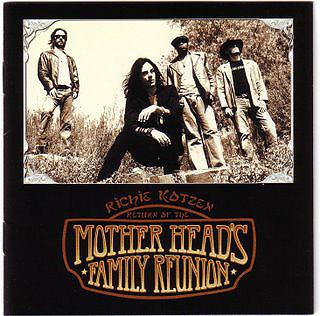

IC: Would you mind sharing what album that was that you were referring to in the deal with Geffen?

RK: Oh, that was Mother Head’s Family Reunion in 1994.

IC: You have this large, loyal, and dedicated fan base around the world, and, in fact, your largest markets are probably abroad rather than domestic. Being from and living in the U.S., what do you attribute this to?

RK: Well, I’m learning something about where my fan base is, and it’s interesting, because the fact of the matter is that the fan base… how can I put this in a way that makes sense? If I’m selling CDs on the Internet, I can see where they’re going, and I would say that at least 50% of the sales are here in the United States. The other 50% are scattered around other parts of the world – be it Japan, Europe, South America. And they’re probably scattered around equally. So the thing that’s odd about that, is that when I’m touring, I’m always touring somewhere else; I’m always touring Europe, I’m always touring South America. I think that has to do, again, with the actual business side of things. I’m finding that people in these other countries, like South America for example, that are music fans that want to get into the music business. So they start seeking out artists they like, and they set up tours and they bring them there, and they’re successful because there’s a fan base there. Now the thing is that they’re taking a big chance. But once they take the chance and see that it’s a success, then they’ll do it again. Do you know what I mean?

IC: Yeah, Yeah.

IC: Yeah, Yeah.

RK: And here in the States, I just haven’t come across any kinds of agents that are willing to do that sort of thing that they do in these other countries. And then the other issue with the United States is that it’s so huge. It’s not like you’re going to Italy and you’re gonna do a seven city tour – you can kind of drive around and around, and it’s not that difficult. But here, there are other variables that make it more complicated. But having said that, I would love to be able to tour here. It’s something that I’ve been looking into, and talking to people about, and maybe that’ll happen. That is possible. Also what happens is if I’m getting an offer to go to Europe for a month and a half, then I’m gonna take it. And then by the time I agree to that, I’m approached by South America for a tour down there the following month. Then more dates are gonna follow for Europe after that. So it’s almost like – whatever comes to the table first, that’s what I’m doing, pretty much.

IC: With your Internet presence expanding, have you seen changes in your fan base? Do you think being more present on the web has changed the way you reach out to your fans and where they come from?

RK: Well, there ends up being more people. There ends up being more people that become aware of you, because there’s that presence. And people will seek out… just because a company says you’re supposed to listen to this particular flavor of the month, or this new band, doesn’t mean that someone isn’t going to say: ‘Well, wait a second. I don’t like that. I like this other kind of thing, and I’m going to go find something that sounds like that.’ And now, obviously with Internet, people can go find that. So it makes everything bigger. I haven’t experienced any of those kinds of issues that are people are complaining about: pirating and this and that. I guess there’s a lot of that going on, but for someone like me, who’s on the level that I’m on – I don’t mean that’s a high level, I mean a lower level as compared to the big music business machine. I’m sort of under the radar, so I haven’t really felt any impact from that. People who are interested in me seem to want to support what I’m doing, and seem happy to download the music and pay for it and not steal it.

IC: Obviously the number one focus of your career is creating and performing music, but how involved are you in the business aspect of your career?

RK: Well, what exactly do you mean by specifically the business? Like, am I booking the shows?

IC: There are artists who only concern themselves with their artistry – they let other people take care of the other parts of their career.

RK: Sure, I know what you mean. I try to do as much as I can, and I try not to put myself in positions that I think are going to be a liability, or a hindrance, or a crutch. I think I’m pretty conscious of what I’m doing. Anything I can’t do, I get someone else to do. Like, I can’t book a tour in South America myself – I need an agent to do that. So I’ll find an agent that I trust, we’ll work out a deal, and we’ll take it from there. If I get a contract, and I read it and it makes sense to me and I understand it, which a lot of times I do, I don’t really feel like I need to show it to anybody and I’ll sign it. But if there’s something in there that I feel weird about, I’ll send it over to the lawyer and have him look at it. So on that level, that’s kind of how it is.

I’m pretty in touch in the sense that I don’t have partners. I’m not trying to go get a record deal and make a dollar a record, when I can sell it myself and get eight dollars a record – that sort of stuff. So like I said, I try not to put myself in a position where I’m going to have some kind of liability or something’s going to slow me down. If something’s going to benefit me, or move things along quicker, then it’s a good choice.

Headroom Inc.

IC: Back in 2002 you actually purchased a whole commercial building in L.A. and established a studio and production company there – Headroom-Inc. What motivated you to make this move in your career?

RK: Well, it doesn’t sound very musical, but the real estate market motivated me to do that. That’s the honest answer. I had come home with Mr. Big, we had done a major tour in Japan – the last tour there was ever to be, supposedly. So I came home, and I wanted something to do, and I was kind of exhausted from music. The other passion I have is buildings, believe it or not. I own a home in the Hollywood Hills, and I’m constantly remodeling it, and it’s my hobby. So I found the building, and partnered up with my father, actually, who’s a great builder, and we did some work on this place and turned it into this really cool studio. The idea was that if I had this place, obviously I could make my records out of it, and by renting studio time I could cover my expenses. But I wasn’t looking to make money in the studio business, because it’s impossible to do that.

So we held it for three years, and at the height of the market – people were going nuts out here in L.A. buying houses. They would be sold before they even came to market, which is insane. Now of course, there are foreclosures everywhere. Anyway, at the height of the market, we found someone who was interested in buying it, and we sold it. That was it – that was the plan. It was an investment. It was fun, because I had a place to work out of, and it was cool to have, as far as showing off, like: ‘Look at this cool place I have.’ But ultimately, it was done as an investment, and that’s what it was and luckily it worked. They don’t always work. Sometimes that stuff can backfire. I was lucky.

IC: So where was Go Faster done?

RK: Go Faster was done in my house. The gear that went down to that studio was pulled out of my house, so when the studio went away, that gear just came back up here. This is where most of my stuff’s done. I think Get Up was the only record that I did all at Headroom, and then Into The Black – half of it was done at Headroom, and then the other half was done here at my house.

IC: Are you using outside engineers and mixers to produce the records, or are you aware of the gear yourself?

RK: I’m aware of all of that. Different things happen. As far as production, like deciding the arrangement or what the drums should play or what the bass should play, I do all that myself, because I hear it, and it’s part of the song to me. So those kinds of things I do myself. I have done records where I’ve engineered and mixed them. On the last record, Go Faster, I ended up mixing it. I had Lole Diro come in, and set the tools up, and then he couldn’t be there to do the record, so I actually did pretty much the whole record without him. I don’t like taking credit for it, so sometimes I’ll put names on there, but most of my records I’ve mixed myself and engineered myself. For some of them, this guy Alex [Todorov] has done work on them, and it’s nice to have someone here.

RK: I’m aware of all of that. Different things happen. As far as production, like deciding the arrangement or what the drums should play or what the bass should play, I do all that myself, because I hear it, and it’s part of the song to me. So those kinds of things I do myself. I have done records where I’ve engineered and mixed them. On the last record, Go Faster, I ended up mixing it. I had Lole Diro come in, and set the tools up, and then he couldn’t be there to do the record, so I actually did pretty much the whole record without him. I don’t like taking credit for it, so sometimes I’ll put names on there, but most of my records I’ve mixed myself and engineered myself. For some of them, this guy Alex [Todorov] has done work on them, and it’s nice to have someone here.

I like having a guy here to press the buttons and do that stuff. It makes it easier, but then at the same time, when I do my vocals… sometimes I might decide to do a vocal at a weird time, because I feel inspired to sing, and I can’t call someone at the last minute to come over, so I go in there and set up the mic. I know the signal chain that I like and I understand all that stuff – how it works. Actually, when I was a kid, before I even committed to doing music fulltime, I was really into electronics, and I used to go into the electronics shop and buy schematics and make radios and motion sensors and all of these crazy things. So there was a weird crossroad where I was playing the guitar, but I could have gone the other way and went to college to be an engineer. And then, for whatever reason, I went right down the road of being a musician. But having a little bit of that background, I have no problem understanding how that stuff works, and if I have to fix something, I can.

IC: I was actually just going to ask you about that. As a young person, at what point did you decide that you wanted to make a career out of music?

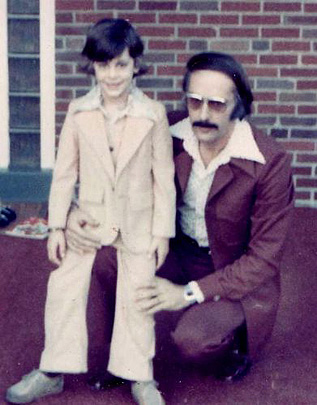

RK: I was very young when family members said: ‘You know, Richie should take piano lessons.’ I was maybe five, and at the time I was always singing, and dancing and trying to entertain my family. I had, back then, a pretty big family. So I would get up on what looked like a stage to me, but was actually part of the fireplace. I’d get up on this fireplace with a ledge and jump around, and do things, so somebody finally said: ‘Get him piano lessons.’ The first things I actually got were a mic stand, a microphone and a tiny little PA system, so I could sing through it. That was the first thing I ever got. There’s a picture somewhere of me dressed up like a rocker, with a long black wig on, and a crazy outfit, and a plastic guitar, with the mic stand and the little speakers there. So it was kind of funny. I’d like to find that picture somewhere. Anyway, from there I took the piano lessons and I didn’t really like it. It didn’t make the sound that I wanted to make, and so I left piano lessons for about a year. I remember being at a yard sale and seeing a guitar, and insisting my dad buy it. I got the lecture: ‘Look, you didn’t play the piano. If I buy this, you’d better practice it.’ I told him: ‘I promise I will.’ At the same time, I was into the band Kiss, and I remember seeing a picture of them holding guitars, and Gene Simmons breathing fire, and thinking: ‘That’s the instrument I wanna play!’ That’s how it started.

Young Richie and his Dad

RK: I did, and I’ll never forget being terrified of my guitar teacher the first time I went. First of all, the first thing he said was that he couldn’t teach me on the guitar my parents bought for me, because it was such a piece of shit. So we went out and bought a better guitar – it was a Gibson Marauder. It looked like a Les Paul, but it wasn’t. That was my first guitar that I learned on. I remember just being afraid of this guy. He was such a crazy-looking hippy – he had long red hair and a long red beard, and lived back in the woods somewhere in Pennsylvania. I remember he had this pointer, and it was a pointer where you press the button and the thing just shoots out the music paper. So he could tap onto the page and still stay in his chair, he didn’t have to lean forward. I didn’t know what the hell it was, and he pressed and it came out – I thought it was a switchblade. I almost dropped my guitar – I got so scared. I thought he was gonna stab me (laughs). For the first month, I was terrified of my guitar teacher.

IC: So how old were you when you got discovered by [Shrapnel Records founder] Mike Varney?

RK: Well, I was 17 when I got in the [Guitar Player Magazine] Spotlight column, and then I was 18 when he signed me. When I made that record, I was 18, and by the time it came out 1989, I had just turned 19. That was prior to me moving to California. I still lived in Pennsylvania. After I did that record, I did some tracks. I remember being in L.A. – they did a cover story with me, Reb Beach and Nuno [Bettencourt.] That was before I was going to San Francisco to make my second record. The big thing was that I was going to be singing on the second record, which I had never done before. I sang with my cover band and stuff, but it was live. I’d never sung on a record. I was pretty nervous. I ended up going up to the Bay area, and actually living up there for about three months; working on and off on the record.

Then I came back to Pennsylvania, and that record was heard by Interscope – a new label at the time. They had bought my deal from Shrapnel and signed me… vocal records, and do the rock thing. They gave me some money, and I moved to L.A. I tricked my parents, because they didn’t want me to leave. I came out here to do a benefit show, and I was staying with a friend of mine. I said: ‘Let me look at some places.’ I found a place that was furnished for a reasonable amount of money, and I went in there and put the deposit down. I called home and said: ‘You’ve gotta send me some more clothes, I’m not coming back.’ (laughs) It’s pretty funny. I spent a year here, trying to get this record going for Interscope, and it was constant fighting. I wanted to make this sorta soul record, and they wanted me to do a more hard rock record, and my heart wasn’t in making that kind of record. They ended up dropping me, and right when they dropped me is when I got the Poison gig, so that kept me in L.A. Then, with the rest, it’s pretty much obvious what happened.

IC: How did you get the Poison gig?

RK: The guy that signed me at Interscope used to work at Capitol, and he brought Poison from whatever label they were on over to Capitol. He was their A&R guy. When I was having problems at Interscope, fighting about the direction, at one point I said: ‘You should just release me, this isn’t working.’ I didn’t really have any options. I don’t even know why I was so overly confident in what I was capable of doing. I got so frustrated with them not being able to facilitate that for me. In retrospect, I understand. It’s a big investment for them, and they’re not gonna make a record with someone that they don’t want to make, or that they don’t think they can sell. It’s not the music creative arts – it’s the music business.

Richie Kotzen with Poison

Anyway, during all this turmoil, he said: ‘Listen, I got a phone call from Poison.’ I guess it must have been from Bret Michaels. He said: ‘They know about you, they’ve read about you in the guitar magazines.’ By then, I was already known as a guitar player, so it wasn’t hard for them to see me in the press and stuff. He said: ‘They are interested in you auditioning and possibly replacing C.C. DeVille as the new guitar player of Poison. I think you should do it. I think that you’re young, I know what kind of record you want to make, but I don’t think it’s time now to make that record. I think if you go do this, by the time you’re done with it, you’ll have a more clear idea of who you are as a recording artist.’ It was all just talk. So I went over and I met Bret. We hit it off and that’s pretty much how I got the gig.

I auditioned playing their songs, which I totally butchered, because I figured in my mind: ‘Well, this is just simple.’ I think I’d learned them without even picking up the guitar – in my head I was listening to them. I thought: ‘Oh, I got that. That’s C, D – I know what they’re doing.’ So I got there, and of course I didn’t know what the hell the parts were and I screwed it up. I had a problem with my amp, I remember smoke came out of it. So then Bret goes: ‘Well, do you have any songs of your own?’ I said: ‘Well, yeah, I’ve got a lot.’ I played him a song that ended up being ‘Fire And Ice,’ the second single on the record, and then I played a song called ‘Stand,’ which ended up being the first single. I think by having played the songs, they realized that I would be an asset to the band because I wrote. Then we played together for another two weeks, and at the end of two weeks, I didn’t really know if I was in the band or not, because no one said anything. So they sat me down, and they played this game with me to make me think that I wasn’t gonna get the gig, and then at the end of it they told me I had the gig.

Richie Kotzen with PoisonSo it was kind of an emotional rollercoaster there for a second. It was fun, man. It was fun making that record. I love the record that we made. It sounds great, it was a fun experience – but once I got on the road is when it became kind of ugly. I think a lot of it was based in the fact that the morale of the band was fucked up, because up until that point they were used to putting a record out and having their songs spike to the top ten instantly: boom, boom, boom. ‘Stand’ got to about 14 or 16, and it didn’t stay there very long. The record went gold, and eventually went platinum, but the point is: it wasn’t doing what their records normally did, but none of those kinds of bands were, because grunge had kind of taken over. MTV played the hell out of our first video – it was on the most-wanted constantly. Then by the time Capitol waited to put out the second single, MTV was like: ‘We don’t wanna anything to do with it. We’re into playing these other kinds of bands now.’ And then that was the end of it.

IC: Tracking back a few years: do you remember what you sent in to Varney to get into the Spotlight column?

RK: I do, and it was a funny little game that I played, because I had finally gotten four songs that I thought as a guitar player was the best I could possibly do. Back then, I didn’t really have things together. I was recording things that I thought would get his attention, based on what he was releasing, because my obsession at age 17 was getting into that column. I didn’t have the knowledge and the confidence that I have now. I didn’t know it then. So I was just trying anything I could – crazy licks and whatever.

So I came up with four songs that I thought made sense, and I sent it to him, and I kept sending this tape. And every time I would send it I would change the sequence. So if I sent a tape, and a week or two went by and I didn’t hear anything, I’d make another one and change the order. I was relentless. Somehow, I got his phone number, and I would call and leave messages and say: ‘Hey, I just wanted to know if you got the tape.’ I was obsessed with getting in this fucking column. I used to come home from gigs and look at the answering machine and see no calls, and curse like a fucking madman: ‘Cocksucker! I can’t believe he didn’t fucking call me! This motherfucker calls everybody in this fucking magazine! I should…’ That was my mindset as a 17 year-old kid.

All of a sudden, one summer I’m sitting in the kitchen and the phone rings and my friend, who had moved to Boston to go to Berklee, said: ‘Man, you’re such an asshole.’ I said: ‘What are you talking about?’ He goes: ‘Why would you not tell me that you’re in Guitar Player magazine?’ I went: ‘Well, because I’m not. What are you saying?’ He said: ‘You are too. I’m staring at your picture right here.’ I said: ‘Man, if you’re fucking with me, I’m gonna kill you. I’ve been trying to get in that magazine.’ He said: ‘Well you’re in it, and I’ll read you the article.’ And he reads it, and I’m listening to it, and there’s things in there… like, when I gave my influences, I knew that he didn’t know what influences I was gonna say, so I knew it was real then. I went: ‘Holy shit! They just put me in there but they never called!’

All of a sudden, one summer I’m sitting in the kitchen and the phone rings and my friend, who had moved to Boston to go to Berklee, said: ‘Man, you’re such an asshole.’ I said: ‘What are you talking about?’ He goes: ‘Why would you not tell me that you’re in Guitar Player magazine?’ I went: ‘Well, because I’m not. What are you saying?’ He said: ‘You are too. I’m staring at your picture right here.’ I said: ‘Man, if you’re fucking with me, I’m gonna kill you. I’ve been trying to get in that magazine.’ He said: ‘Well you’re in it, and I’ll read you the article.’ And he reads it, and I’m listening to it, and there’s things in there… like, when I gave my influences, I knew that he didn’t know what influences I was gonna say, so I knew it was real then. I went: ‘Holy shit! They just put me in there but they never called!’

Then about a month or two later, Mike Varney calls and says: ‘I’ve been thinking about doing a record with you. I don’t know what to do with you. I’ve done a lot of these records now, but I think you’re very interesting, and I’d like to do a record. I might want to do what I did with Marty and Jason, and I might team you up with somebody.’ Because there was another guitar player in New Jersey that he spotlighted, that he was thinking about signing. So he had me and this guy Steve Ross start writing together. So we sent in a couple of songs that we did together, and we worked our asses off.

Then something kind of weird happened, I don’t remember clearly what happened. Steve was sending his stuff, I was sending my stuff, and we were sending stuff that we did together. According to Mike, somehow my productivity went off the chain. Every week he would get a tape with four or five songs. I was recording like a madman, and I guess after hearing some of this stuff, Mike decided: ‘Well, this kid’s putting a lot of work into this, and I think it’s neat.’ So he ended up just signing me, and I think years later he did a record with Steve. He ended up signing me, and then we did this record.

By the time that record came out, and it was time for the next record, I said: ‘I don’t really feel like being an instrumentalist. I’ve always been in a band, and I don’t want to make that kind of music.’ I wanted to get on Shrapnel, but once I got on there I wanted to change it. So then we decided to do a vocal record, and he set me up to try out singers, so I started trying out singers one after the next. Then there was one demo where I sang it myself, and that’s when he said: ‘You know what? I like your voice better than anybody you’re auditioning. I think you should sing on it.’ So that’s when I started really taking it more seriously, and listening to and recording myself, and all of that bullshit. That’s a long-winded explanation (laughs).

IC: Very interesting, though. I want to take a minute to talk about your gear. Your tone on Live in Sao Paulo is awesome – there’s all the Strat twang, but you keep it sounding warm and smooth throughout. Can you talk about that Strat, and your general concept of tone?

RK: Absolutely. First of all, I have two signature models with Fender – one’s a Strat, and one’s a Tele. I was playing the Strat. Most of the sound has less to do with the guitar – there are other Strats I could play that would probably sound similar. It’s more to do with where I’m playing it, and how I set my amp. The dynamic range of an amp needs to be there. I can’t really do what I do on amp that’s heavily compressed. What I mean is that kind of sound where the distortion is full on and full gain, and then when you turn the volume down, the amp needs to become responsive. The most responsive amp would probably be a Fender Vibro-King.

RK: Absolutely. First of all, I have two signature models with Fender – one’s a Strat, and one’s a Tele. I was playing the Strat. Most of the sound has less to do with the guitar – there are other Strats I could play that would probably sound similar. It’s more to do with where I’m playing it, and how I set my amp. The dynamic range of an amp needs to be there. I can’t really do what I do on amp that’s heavily compressed. What I mean is that kind of sound where the distortion is full on and full gain, and then when you turn the volume down, the amp needs to become responsive. The most responsive amp would probably be a Fender Vibro-King.

The amp that I use is an English amp called Cornford, and I have a model with them that I developed; a 100 watt amp that’s a monster amp. It’s super loud, very clear and very responsive. So when I have the volume all the way up, there’s my lead tone and there’s my heavy rhythm tone, depending on how hard I play. Then as I roll the volume back, it cleans up. Then it’s a switch with that amp, that if I press the switch, it’s almost like taking the gain down a few notches. So if I put the volume on my guitar back to ten, now I’m getting a crunchy rhythm tone, and it’s not the full on sort of lead tone. It’s not a two-channel amp, but it almost works that way, in a strange way. We spent a lot of time finding the better resistors to use, so when you press that switch and it cuts the gain it doesn’t mess with the volume. It’s a very subtle move – it’s almost like going from ten to six or seven or something, if you move the knob yourself. So that’s a cool feature.

But having said all that, the amp I use on that record is not my signature amp (laughs). The amp that I used is a Marshall JCM 800. That’s because we couldn’t get these Cornford amps down in Brazil, and it was unrealistic for me to bring or ship it. It was prohibitive. So I ended up using a JCM 800 when I did that tour. But as long as an amp is a real amp and a good amp – I shouldn’t say this because probably Cornford will want to kill me – I’m still gonna sound like me. As long as the amp isn’t one of those digital amps that’s totally fuzzed out or some kind of styled amplifier, I’m still gonna sound like me.

IC: I wouldn’t call any of your lead tones high-gain, but you do have quite a bit of drive going on. Despite that, the twang and the character of the guitar still come through in the sound. Do you use any special kind of pickups, overdrive boxes, or anything like that?

RK: The pickups I use are made by DiMarzio. Unfortunately, I don’t know the name of the ones in the Strat – I want to say Twang King… I think that’s what it is. Some of my guitars from the Custom Shop had Texas Specials in them, and the guitar that I played on that South American tour is a hybrid guitar, because I had broken the neck. The body is a Custom Shop body, and a Richie Kotzen neck. That original guitar is what they used to copy my model, so when I switched from the signature model to that guitar, you can’t really tell the difference. I mean, I know the difference, but it’s the same instrument. The only thing is, the guitar that I played with the Custom Shop body has the special pickups in it, and I don’t know that they sound any better than the DiMarzios that I have.

I actually remember doing a gig and breaking a string and switching to the other guitar, and the other guitar sounding better than the one with those pickups. But, I could have been drunk. My point is, I don’t put a lot of merit into all those things. Certain kinds of pickups that are radically different, like the ones with the rails that I had in my Telecaster, they sound totally different. But it’s just wire wound around a magnet, and the more wire you put, the louder it is. These pickups aren’t terribly loud. That’s probably what it is – the pickups aren’t really that hot, so that’s why when I do get an overdrive sound you still hear the twang in the guitar. If pickups were too hot, you would lose all that sense of the instrument.

I actually remember doing a gig and breaking a string and switching to the other guitar, and the other guitar sounding better than the one with those pickups. But, I could have been drunk. My point is, I don’t put a lot of merit into all those things. Certain kinds of pickups that are radically different, like the ones with the rails that I had in my Telecaster, they sound totally different. But it’s just wire wound around a magnet, and the more wire you put, the louder it is. These pickups aren’t terribly loud. That’s probably what it is – the pickups aren’t really that hot, so that’s why when I do get an overdrive sound you still hear the twang in the guitar. If pickups were too hot, you would lose all that sense of the instrument.

IC: Interesting. So basically it’s your guitar going straight into the amp, and you’ve got the footswitch to control the gain stage. Is that it?

RK: Yeah, although in Brazil I didn’t have that amp, so what I had was an overdrive pedal. I had a tuner and an overdrive pedal.

IC: What kind of overdrive pedal did you use?

RK: It’s by a company called Sobbat that’s based in Japan, and this man, over the years, would send me pedals. I never knew what was coming – I’d just go outside and there’d be a pedal sitting there for me in a box. They’re pretty cool. He hand-wires them, they have a good sound, they have some cool features, and that’s it. That was all I had. That was my rig – my tuner, that pedal and one guitar.

IC: On the album Tilt that you did with Greg Howe, there’s a song called ‘Tarnished With Age’ that has a very cool wah part towards the beginning. Is that you?

RK: I wanna hear it… I don’t know! I’d have to hear it, but I guess you could tell which is me. I think we’re even panned to different sides. Maybe I did play a wah on there. I’m trying to remember what I did on that record, I haven’t heard it in so many years. But if it sounds like me, it’s probably me. If it’s not, then Greg played a great wah part. Greg’s amazing, he’s probably my favorite guy that ever came out on Shrapnel, and the irony’s that we grew up about 30-40 miles from each other.

IC: That’s right, he’s from Pennsylvania, as well. Do you guys plan on doing any more collaboration anytime soon?

RK: No, not musically. There’s something he has in the works that I was gonna participate in. It’s a very cool idea, I can’t say really what it is, but it’s based on…

IC: The online instruction thing?

RK: Ok, if you know about it, then that’s that. So he was telling me about it, and it seemed very cool. So I might do something like that with him. Well, he’s just moved to California, so I played the House Of Blues recently, and he was there, and then afterwards we came to the house and hung out. I really like Greg, he’s great.

IC: Now for something entirely different – can you tell me something that you never discuss in interviews?

RK: Something that I don’t discuss… I don’t know. That’s a weird question, because I only respond to what I’m talking about. You know what I’m saying? (laughs) If someone says ‘What is your address?’ I probably would not say that in an interview, I probably would not discuss that.

IC: For sure. I find that asking this question always yields interesting results.

IC: For sure. I find that asking this question always yields interesting results.

RK: It’s a very good question! Because it makes you think, and then it makes you worry, like: ‘Shit! I hope I didn’t say something that I shouldn’t have said.’ But, that’s funny. Good.

IC: You’re back home, you’ve got the record out – what’s a typical day like for you?

RK: Well, there are three things that go on. The most important thing is I try to spend as much time with my daughter as I can, which is great because she lives very close to me. Then, there is my house – which, as I said earlier, I’m always working on. The latest thing there is I’m remodeling a bathroom, and I did something very cool – I made my first arch. When you go into the shower, it’s in the shape of an arch, and I never did that before. It’s a whole process to make that happen, so that was kind of exciting for me (laughs). Remodeling the bathroom is what’s happening here now.

Then, creatively, I’m working on some new music, and I don’t know when it’s going to be released. I’m guessing it won’t be until the end of the year, or even next year. This is going to be the coolest record I ever made, by far. The thing is, it’s not a guitar player’s record. I’m working with somebody else, some of the songs are my own, we wrote some together, I co-wrote some with some other people – it’s like if you picture Sam & Dave, Sly & The Family Stone and Al Green done by me. We have horn players, we’ve got background singers – it really came out cool. Because it’s not us trying to sound like those people, it’s just that it sounds like it would have been recorded back when they were doing that thing, but it just has a modern sound to it because it’s now. So it’s not like we’re in there trying to copy any of this stuff.

This is the record I always wanted to make. If I could have made this record back when I was signed to the major labels, this is the kind of record I wanted to make then, but I wasn’t capable of making it then. So I’m pretty excited about it, and it’s pretty much done. I just have to wait and see what I’m gonna do with it and we have to figure out what makes sense. I’ve been writing, and now I gotta get ready to go on my tour. That’s always stressful.

IC: Do you have any advice for upcoming musicians?

RK: Well, upcoming meaning young musicians that want to make a future and a career in the music business, right?

IC: For sure.

RK: I think that the thing is this: I think as long as your intent is pure, you’ll be okay. In other words, if you intend to play the guitar because you want to get in a band, because you want to be famous, and because you want to be rich and all of the things that come with that, you’re setting yourself up for a very miserable, frustrating life with a lot of disappointment, because that doesn’t happen to very many people… it happens hardly for anybody. If you’re getting into music because you love music, and you love being creative and the process of putting yourself into a song and making something from nothing and all that sort of thing, then it’s a great thing. You’ll have a very fulfilled life as a music maker, a musician and a creative person. I think that the intent has to be pure and honest. I think that if you have another kind of agenda, then you’re gonna be frustrated.

When you go out and try to get a record deal, and now anymore… don’t bother because record companies don’t know what they’re doing… but I think going out and getting a record deal, the minute you set out on that road, you’re setting yourself up for depression, heartbreak, misery and all of those things. Because suddenly you’ve got something that felt great and creative and inspired, and made you feel really good – but now you’re asking somebody else to listen to it and feel the same way about it, enough that they’re going to spend millions of dollars to market and promote you to the entire world. And if they don’t agree with you, it’s going to affect you. You can say that it doesn’t, but it is. The minute you let that go, and don’t care and don’t seek that out, then you keep it innocent, pure and fun and enjoyable. I just think that’s important.

When you go out and try to get a record deal, and now anymore… don’t bother because record companies don’t know what they’re doing… but I think going out and getting a record deal, the minute you set out on that road, you’re setting yourself up for depression, heartbreak, misery and all of those things. Because suddenly you’ve got something that felt great and creative and inspired, and made you feel really good – but now you’re asking somebody else to listen to it and feel the same way about it, enough that they’re going to spend millions of dollars to market and promote you to the entire world. And if they don’t agree with you, it’s going to affect you. You can say that it doesn’t, but it is. The minute you let that go, and don’t care and don’t seek that out, then you keep it innocent, pure and fun and enjoyable. I just think that’s important.

If you say to yourself: ‘Well, I want to become known and successful.’ you’re still kind of missing the boat. You have to create something that then becomes successful because of what it is naturally, not because you force it down somebody’s throat. If something gets recognized, if you create something and people hear it and they respond to it, that’s a natural thing. But if you create something expecting it to be loved and adored by everyone, then you’re going to be miserable. I think that’s the fundamental of what ruins playing music for people.

Some people play music their whole lives and love it, and then they get to the point where they don’t even like music anymore. Because they’ve missed the whole innocence of what makes you start to play music. When I was a kid, I wasn’t thinking of Ferraris or hot chicks, I was thinking: ‘Music is cool. It sounds cool. It’s fun. I want to make my own songs, too, like Pete Townsend does.’ That’s the kind of mentality – you’ve gotta keep that somewhere.

Special thanks to Chris Dingman for the transcription of this interview.