Guthrie Govan is one of the most versatile guitarists around. His vast range of influences and terrifying technique has allowed him to develop what seems to be a limitless ability to adapt to any style of music, all the while also maintaining his own distinct fusion sound.

Guthrie Govan is one of the most versatile guitarists around. His vast range of influences and terrifying technique has allowed him to develop what seems to be a limitless ability to adapt to any style of music, all the while also maintaining his own distinct fusion sound.

Guthrie has established his presence playing in bands such as Asia, The Young Punx, and GPS, as well as working for the UK magazine Guitar Techniques, where among other things he contributed spot-on transcriptions and performances of solos by players such as Shawn Lane and Eric Johnson (to fully appreciate the depth of this task, give it a try!). In 1993 he won Guitarist magazine’s “Guitarist of the Year” competition.

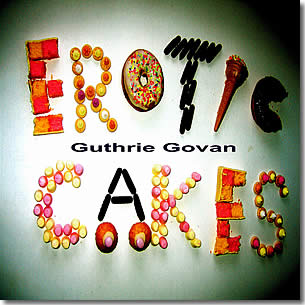

It wasn’t until 2006 that Guthrie fully established himself as a solo artist with his release of Erotic Cakes, an all-instrumental magnum opus, which includes the fan-favorite “Wonderful Slippery Thing,” the same composition which won him the aforementioned Guitarist competition. I had the great pleasure of speaking with Guthrie at the 2009 NAMM Convention in Anaheim, CA:

IC: How are you, man?

GG: Getting there. It’s a grueling show. I generally find at the end of the third day, I’ve lost my voice. No one realizes how loud it is at a NAMM show until it’s over.

IC: What’s a typical day like for you at the NAMM show?

GG: I turn up with a hangover, I drink coffee, people come up and ask me when the next album’s coming out, and they ask me about the amps, I try things, and I lose my voice – a couple of days of that.

IC: So let’s get to the album question!

GG: Ok, yeah, let’s kill the album question now. It’s my New Year’s resolution to carve a lump out of my calendar and say ‘no’ to teaching and playing, and just hide in a room and be a crazy nerd and come out pale, brandishing an album that’s complete and full.

But it is tough in this line of work. You never know when a gig or a clinic or a tour or something like that is gonna come up. You generally just have to say ‘yes’ to everything. In the words of John Lennon, ‘life is what happens when you’re making other plans,’ so the album is very much the other plan. This year, I’m going to make sure it happens, because I want to hear the next album.

IC: Which of your many musical pursuits has been the most important in maintaining your career as a professional musician?

GG: Teaching is at the backbone. Teaching is the closest a musician can get to having a proper job. I get a check at the end of every month, which is how I make rent. So it’s stable. I don’t think anyone ever took up guitar thinking one day, if they tried really hard, they might become a teacher. It’s a cool thing, but I’m really trying to keep sight of why I like playing, which is playing with people, playing to people. Anytime a gig pops up, I have to say ‘yes.’

IC: Do you do any session work?

GG: Some. I’m doing a lot of something called song recreation, which is a sort of session work. Picture the dance community for a moment. [imitates a pulsing club beat] A lot of times people will do a demo track for an album, and they’ll use four bars of a James Brown record or something like that. Then when the contract’s been signed and they’re doing the finished version of the album, they realize that they can’t afford to pay the copyright clearance to use the original, or they aren’t allowed to – James Brown says ‘no.’ So there’s a company that basically copies these two to four bar chunks.

It’s fun. Every one is a different challenge. We just did some disco, and then pretty soon we have to do an 80’s Genesis track. My part is hearing the guitar sound and trying to guess what gear people used, and then trying to recreate it. It’s fun work. Someone can send me an MP3 and say: ‘Can you turn this around in twelve hours?’ Sometimes I end up on pop records that I don’t know. I turned up on the new Sugababes album, and I had no idea. They just said: ‘Can you recreate this for me?’ ‘Yeah.’

It’s fun. Every one is a different challenge. We just did some disco, and then pretty soon we have to do an 80’s Genesis track. My part is hearing the guitar sound and trying to guess what gear people used, and then trying to recreate it. It’s fun work. Someone can send me an MP3 and say: ‘Can you turn this around in twelve hours?’ Sometimes I end up on pop records that I don’t know. I turned up on the new Sugababes album, and I had no idea. They just said: ‘Can you recreate this for me?’ ‘Yeah.’

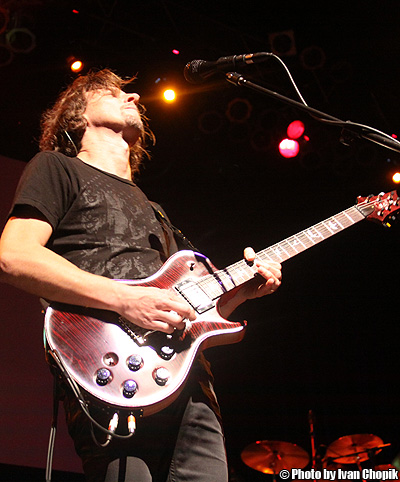

IC: Can you tell us about your Suhr signature model?

GG: Yeah, I can tell you all about it. All Suhr guitars are my favorites – take that for granted. They’re flawlessly constructed, nice work on the steel frets, the Plek job (www.plek.com) – they play themselves.

IC: When did you first get in touch with them?

GG: It was three or fours years ago. I was doing a clinic at Tone Merchants. I tried one there, I liked it, I got involved with the company, and they’ve been really good to me. Any opportunity I get to plug Suhr is a welcome opportunity. As far as my signature guitar, it’s based on the more heavy metal shape that they make. It’s got 24 frets, a sculpted neck joint, but unlike the standard model, I’ve got a grown-up trem – a non-locking trem, which doesn’t do the circus tricks. For me, it feels better, because I hit the strings hard sometimes, and with a Floyd or similar, you lose the attack. The springs and the general wobbliness of the bridge will soak up the duration of the damn notes.

IC: You also get some note warble when you do that.

GG: [Makes warbling sounds with his lips and laughs] You don’t want that in your life. So I’ve come back to the two-post bridge, but it’s non-locking – it doesn’t go as far. It’s better for the Jeff Beck sort of stuff, with a Tremol-No fixed in the back. It’s such a simple idea… you tighten the thumbscrews, and then the bridge isn’t flexing anymore. It’s a really, really basic idea – it works really well. You just reach behind and tighten these two things, and suddenly all your country licks, your bends, come through. It sounds in tune, you can go into D without bringing another guitar on the plane – it’s just practical.

___

[Balding man walks through camera frame in front of Guthrie]

[Balding man walks through camera frame in front of Guthrie]

GG: You’ve got a clip of someone’s head.

IC: We can cut that out.

GG: No, it looks good. It’s good with the head there…

But I haven’t talked nearly enough about my lovely guitar!

IC: Tell us about it.

___

GG: It’s got a mahogany neck, a mahogany body, and a maple top. The fingerboard’s pao ferro – it responds a little quicker, and it’s not as hard to work on as ebony.

IC: The only other guitar I can think of right now that uses pao ferro for the fretboard is the Stevie Ray Vaughan Strat.

GG: Does it? I think Reb Beach is a fan of it, as well. It’s good with the mahogany neck. I was raised on old Gibsons, and that’s where my choice in neck woods comes from. I have an old [ES-]335. With a mahogany neck if you play an E string and then tilt the guitar down so it’s facing the floor, the E is nearly a quarter flat. It’s a really wimpy neck. Whereas with pao ferro, it seems to give it a bit of stability, and you still get a nice EQ on it.

IC: What’s your signal chain? Do you go from the guitar straight to the amp?

GG: It depends on the gig. I am a fan of pedals, but Cornford amps don’t really need overdrive pedals. There are certain overdrive pedals I really like – for example, the Zendrive. That has a really good Robben Ford-y, Dumble type feel. Xotic effects, for the opposite reason – they’re very transparent. It still sounds exactly like the guitar and exactly like the amp.

IC: So you just get a little more juice?

GG: Yeah, it’s building on what you’ve got rather than trying to color it. So I carry one of those, for if I have to use a rental amp, or I can’t turn up as loud as I want to.

IC: So let’s talk about your record Erotic Cakes. First of all, how did the name come about?

IC: So let’s talk about your record Erotic Cakes. First of all, how did the name come about?

GG: Because I’m a Simpsons fan, as everyone should be. Perhaps you remember a 3D rendered episode. I think it was in a Halloween special – it was the last section. [The short Homer from the episode Treehouse of Horror VI in Season Seven] Homer is stuck in this world of real-looking 3D, and he’s terrified, because he’s never seen anything like this before. And that’s what stops Homer panicking, makes him feel at home – he finds a shop called Erotic Cakes, and all is well in the world of Homer. It’s one of the more surreal Simpsons episodes.

IC: How was that album recorded? I understand you did it in bits and pieces.

GG: It took a long time. It was a very painful… [laughs] labor. I recorded various bits of it a number of times. The whole album was the idea of Cornford Records – it was those guys who nagged me into doing the album, and persuaded me that someone might want to hear it. The ears of the operation belong to Jan Cyrka. Some of these guys perhaps know Jan Cyrka – he’s a tremendous guitar player from back in the 90’s, known for doing something along the Steve Vai lines, but more lyrical and melodic – that’s mad stuff. Jan is more in the production line of things now, and he’s the guy who runs the bluesjamtracks.com company.

Jan has titanium eardrums – he hears everything. So we recorded the drums in a drum studio, then the guitars, and he said: ‘The drums don’t sound good enough.’ So he wanted to record those again. So we did, and they sounded great. Then all of a sudden the guitars didn’t sound good enough. So finally we said: ‘Fuck it!’ Can I say that? That’s what happened. I’m just telling it like it is. [laughs]

Finally, what happened – Richie Kotzen [Click HERE to view GuitarMessenger.com’s interview with Ritchie] was a friend of Cornford. He had a lovely studio in LA, so we went there. They’ve got a great live room, Neve Channel strips, lots of guitars. Here’s a little bit of trivia for you: that was the last complicated album that will ever be recorded at that studio.

IC: One of the coolest things about your playing is your ability to flawlessly recreate the styles of so many other players. At the same time, though, you still have your own signature sound. Who were some of your biggest influences growing up, and how have those changed over the years?

GG: This is going to sound weird, but when I was three years old, it was 50’s Elvis.

IC: You started playing when you were three years old?

GG: That’s what they tell me – I don’t remember. It was a long time ago. But, yeah, it was all 50’s rock-and-roll – raw, energetic, fiery stuff that’s not about the chord progressions but how sincerely you play it. Still, a lot of it sounds really fresh and alive. So I learned about four million Jerry Lee Lewis songs, and Chuck Berry songs, Elvis songs – all that stuff. Then I started hearing Hendrix and Cream-era Clapton, which made me think: ‘You don’t just have to play chords on the guitar. Your guitar has a voice of its own.’

IC: The ‘woman tone.’

GG: Yeah, like that good stuff. I raided my parents’ records, so I picked up their taste. I heard all the blues-rock classics and stuff.

___

[Man with curly hair walks through camera frame in front of Guthrie]

[Man with curly hair walks through camera frame in front of Guthrie]

There’s another head, more ornate than the first head.

IC: There are a whole variety of heads here at NAMM 2009.

GG: Let the good times roll. [laughs]

IC: So we were talking about your influences, and what you discovered in your parents’ record collection.

___

GG: Yes, Joe Pass. I thought: ‘What the hell is this doing here?’ There would be surprises. There’d be Pacini or West Side Story in there amongst all the 60’s stoner rock.

IC: So you got into jazz at a pretty young age.

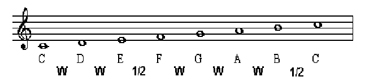

GG: Yeah. I didn’t know the names of anything, so I just tried to make chord shapes that sounded like his [Joe Pass’] chord shapes. Then, I went to the library and I read some books about theory, just to find out the names for the sounds that I’d learned – which is kind of the way I teach to this day. The sound is the important thing. It doesn’t matter if you know the names for the nine positions, but – can you sing that? Do you know when to use that scale? Do you know what chords sound right?

I pretty much learned that way, by copying stuff off of records, and this was back in the Stone Age. There was no Internet, there were not guitar magazines with transcriptions – you’re on your own, pal. In my case, my dad knew about five chords and a couple of blues licks, so he shared those with me. He then said: ‘The only thing I can tell you now is just play like you mean it. Timing is more important than how much you know.’ I think he was right, though I still tried to learn a bit more than five chords and then some licks.

IC: In the Larry Carlton style video you did for bluesjamtracks.com, I hear some lines that sound like horn lines. Are you influenced by horn players?

GG: Yeah, it’s all music. I have this thing – anything I hear, I want to make the same sound. I’m like a Lyrebird. Google Lyrebird-Earth, and you will hear the noises that Lyrebird is capable of reproducing: cameras, chainsaws, anything that it hears in its environment, what’s left of the rainforest – it copies it, it’s eerie. So, I’m at the lower level of things: ring tones, ice cream vans, TV things, and yeah, saxophones and piano, whatever.

IC: What do you like to listen to in your spare time?

GG: No sweep arpeggios. The ultra-technical type of playing, I try to stay away from – unless there’s a real spark there, unless there’s something beyond the technique. Like someone like Bumblefoot; yes, there’s a lot of technique there, but there’s this deeply disturbed mind, and I mean that in a beautiful way. I love Ron’s stuff, but the thing that turns me on about it isn’t the phenomenal technique, it’s the thinking behind it. Players like Mattias Eklundh, Shawn Lane and those guys – they were special. Most of the people with metronomes with nine octave sweep arpeggios don’t have that extra x-factor. You know who the special technical players are.

There’s one I like now. I’m very intrigued by this guy, I don’t know enough about him: Alex Machacek. He’s this Austrian guy, I met him at the Baked Potato and we drank too much. His album is ridiculous.

IC: Oh yeah?

GG: I think he’s moved to LA from Europe, and is teaching at MI [Musician’s Institute] now – fashioning a new life for himself over here where it’s sunny all the time. To me, I hear bits of Coltrane and bits of Zappa. He had me at Zappa, because I’m the world’s biggest Zappa fan. Yeah, everyone should check him out.

IC: What’s a typical day at home like for you?

GG: On a typical day, I wouldn’t be at home. For this past year, I seem to spend most of my life in an airport of some kind. I’m in several bands, I play gigs for various people, and it’s always in a country where I don’t live. So there’s a lot of traveling, and it’s hard to find time just to be settled and get used to living at home.

IC: What band projects do you have going right now? Are you still playing with Asia?

GG: Well, for legal reasons – Google the details if you feel like, we’re not called Asia anymore. There are two Asias… my Asia is called “Asia Featuring John Payne,” because the other Asia has all the guys who played on the first album. Yeah, we do state fairs and Spinal Tap type gigs – that’s fun. I think we have to do a new album this year.

I’m also in a spin-off group, which is a completely different thing with pretty much the same lineup called GPS, which has something of a prog melodic vibe. In GPS, because no one’s heard of us anyway, we think: ‘Sod it, let’s write 15 minute songs because we’re prog rocksters.’ We don’t have to write the catchy song and say it all in four minutes. With GPS it’s a lot more prog, more crazy. We owe the German record company a GPS album this year, as well.

I also play in a techno sort of thing – The Young Punx. That’s a completely different set of challenges, especially live, where I have to plug my guitar into about a hundred patches for a 50 minute set.

IC: That’s something different!

GG: Yeah, I like it. The people who go and see that band are used to seeing something they get in a CD player – punching the air and pretending they’re some skillful guitarist. But I like the perversity of going in front of those people with a real band: ‘See that? That’s a drummer. He’s hitting things with sticks. See? People make music – CD players don’t make music!’ It feels like missionary work. It’s a lot of fun, especially in Japan, because we play in front of 12,000 screaming people. Once we go back to London, there’s three people there and they’re all on the guest list.

IC: It’s interesting how that works out. Do you do a lot of gigs in Japan?

GG: We don’t do nearly enough gigs in Japan. I have to say this: once you’ve done a gig in Japan, every other gig you do for the rest of your life will be a profound disappointment.

IC: Why do you think that is?

GG: Japanese people care. They really go through things properly. They will not let any tiny thing go wrong. They make you feel really welcome, it’s organized really well, and everything starts on time… contrast that with the Glastonbury Festival, which is the big hippie type festival in England. We had to play there in ten inches of mud, it was miserable – it looked like a bathroom stall. There we are, we’ve traveled that far, we’ve gotten through the gate… and we couldn’t get the soundman out of his bus. The soundman was wasted, he was asleep on the bus, and he said: ‘I’m not coming out, to do my job that I’m being paid to do, unless you get me some drugs.’ So we spoke to the manager, and in the end we decided: ‘Let’s get him some alcohol.’ So about halfway through the set, he came and did some sound.

IC: As a musician involved in so many different projects, what part of your career offers you the most challenges?

GG: All of it. Everything you do has a different set of challenges. I remember one summer I did a few gigs with a Motown covers band. It was good – we had horn sections and many backing singers with many shiny costumes. It was a good tribute band, and playing with those guys all you have to do is: ‘Chack! Tick. Chack! Tick. Chack!’ on two and four for the whole two hour set, and you maybe get an eight bar solo on one of the Lionel Richie lead sheets or something like that. Yeah, so there’s a different challenge there. Because it’s so hypnotic, the challenge is to concentrate and enjoy being part of the snare drum. ‘How short and snappy can I make this? How in time can I make this?’ I used to sit wide-awake for hours just trying to do the perfect snap, where you and the snare are one.

IC: Do you practice in a regimented way?

GG: No, I play whenever I can. I don’t like to call it practice, because it makes it sound like something you don’t want to do, and you have to force yourself to do. Playing has never been like that for me. I just like guitar, and if I have time, I’ll go and I’ll play. Oddly enough, now that I do music for a living, there’s less time to take up the guitar and play.

IC: Do you have any advice that you can give to young musicians aspiring to become professional musicians like yourself?

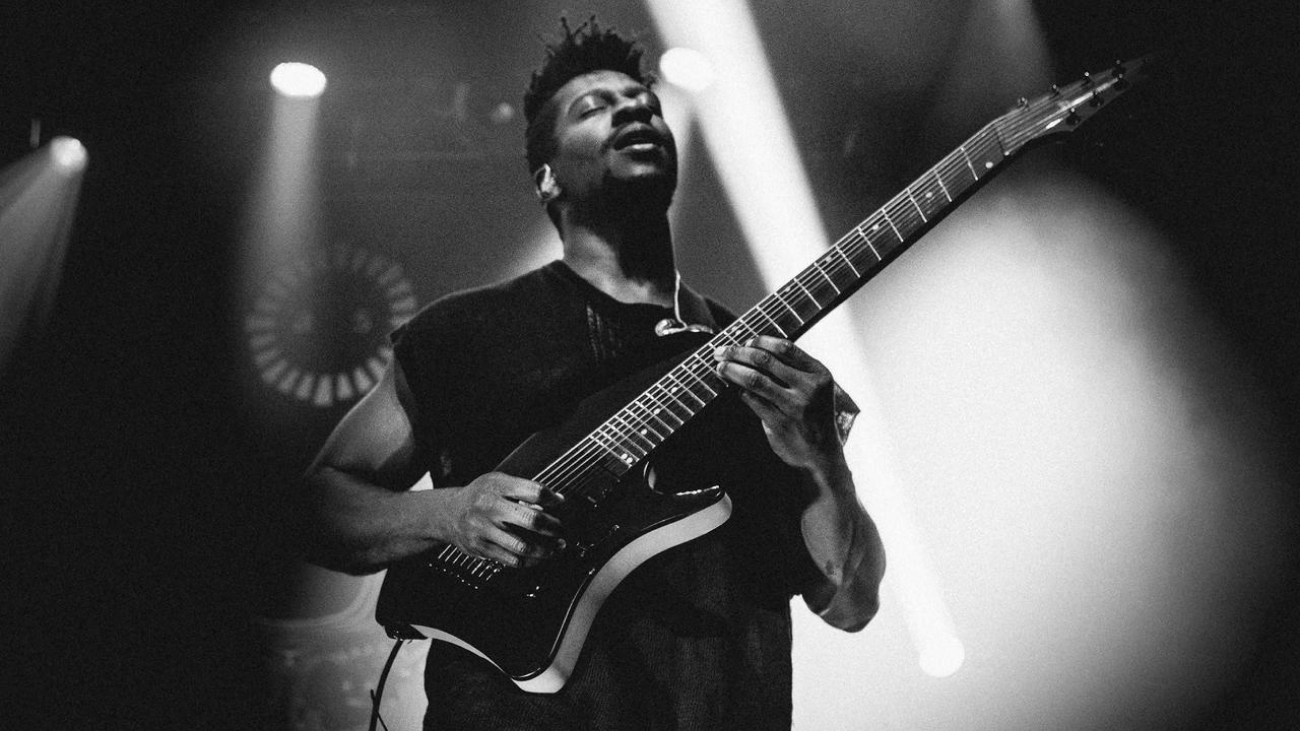

Ivan Chopik with Guthrie Govan in 2009

GG: Don’t do it! It all ends in poverty and tears [laughs]. On a serious note, music is meant to be fun, and that’s important. Sitting in a room with a metronome, punishing yourself, playing arpeggios like they’re Hail Marys – that’s not going to make you love the instrument, or yourself. Some of that’s good, if the music you hear in your head requires that you have great technique, you have to work at great technique. But try to enjoy it. Remember that great technique is often about trying to make something feel easy. If you play something slowly lots of times, and pretend it’s easy, you get to the point where you can play it effortlessly for hours on end without tiring yourself out. And then one day, if you need to do it a little quicker, you find that you can. If something feels easy, that means you’re doing it right.

The problem with the race against the metronome I think is that everyone tenses up, because they think they’re doing something difficult. That’s how you learn bad habits, and give yourself tendonitis and all of that bad stuff. So take it easy, try and make it sound good – sound is really important, and do something with your playing. Do some demos, write music, join a band, join five bands… have fun, sound good, be in time – obvious things.

IC: Guthrie, thanks so much. It’s been a pleasure [In unison with Guthrie]!

GG: Glorious stereo! You’ll never get it that in sync again. Thank you. Cheers.

Very special thanks to Chris Dingman for the transcription of this interview.