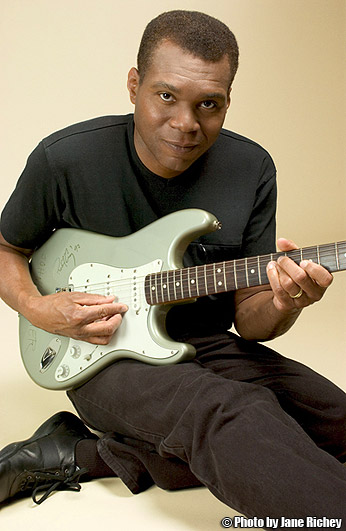

George Bellas is a unique figure in the world of instrumental guitar. His fusion of technical facility and compositional prowess allows him to consistently deliver fresh material that both excites and challenges his listeners. The Dawn of Time, his latest offering, continues to expand the boundaries of his signature sound. At the same time, the record incorporates the neoclassical roots that have been a hallmark of his style since the beginning. I recently had the opportunity to catch up with George and talk about his music:

George Bellas is a unique figure in the world of instrumental guitar. His fusion of technical facility and compositional prowess allows him to consistently deliver fresh material that both excites and challenges his listeners. The Dawn of Time, his latest offering, continues to expand the boundaries of his signature sound. At the same time, the record incorporates the neoclassical roots that have been a hallmark of his style since the beginning. I recently had the opportunity to catch up with George and talk about his music:

IC: Congratulations on completing the new album – The Dawn of Time.

GB: I’m pretty stoked about this new album coming out, man. I finished writing another album in December which I’ve started recording, and I’m writing another one that I’m about halfway through and I’m just super excited about it.

Each new album is always exciting, because for me that means reaching and looking for new things, exploring new ground that I have not worked with before – hopefully without alienating people that liked my past releases, which I think I kinda did on my last two things: Step Into The Future and Planetary Alignment. They were so far out.

With Planetary Alignment I sat there and said: ‘Man, I really want to hear things that I haven’t heard before.’ I’m not reinventing the wheel by any means, but I’m just looking for these things that I haven’t heard in rock music. Some of those are these weird exotic scales – not that I’m the first to use these.

I had my nose deep into Nicolas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus Of Scales And Melodic Patterns. That was a great resource and source of inspiration for me when writing Planetary Alignment. Step Into The Future and Planetary Alignment were pretty far out and very futuristic sounding, as opposed to Mind Over Matter, which was more straight-ahead neoclassical – older concepts that people are more familiar with, I think.

This new album The Dawn Of Time, that will be out on July 16th on Lion Music, kind of goes back to some of my neoclassical roots. Not necessarily repeating anything – I’m not just rehashing the same tunes that I did on my earlier albums, I really reached out as I always try to do, but it does indeed go back to some tonal music. I’ve got some simpler tunes on there, straight-ahead sort of songs, and a few progressive, far-out odd-meter odd-scale pieces on there, too.

IC: There is some excellent material on this record. I’m particularly fond of the lyrical, Romantic Era inspired melodies and chromaticism. Also, right before we got started on the interview I was listening to the Phrygian riff at the beginning of ‘Nightmare Awoken.’ That was really cool, man – really heavy.

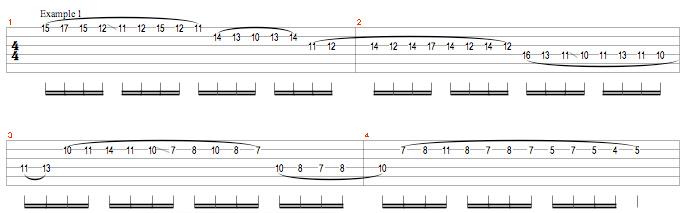

GB: Right on – thanks a lot. Yeah, ‘Nightmare Awoken’ – that’s sort of a creepy, mystical vibe throughout that whole thing. And another thing, you mentioned the lyrical melodies. I just can’t get enough of melodies. In this day and age, especially with younger players, we all have this fascination with developing our technique – which is good.

We all want to play good and proper and all that good stuff, but not for the sake of neglecting great melodies, awesome song forms and exploring new territories with harmonic, melodic and rhythmic concepts. It’s not for everybody. I can’t say ‘Everybody should be doing this.’ If you like what you like, you run with that, but don’t be afraid to try new things that you haven’t heard of either.

But yeah, ‘Nightmare Awoken’ was a lot of fun. On that particular track, if I remember correctly, I used the JCM 800 for the rhythm and most of the solos and a Strat, along with a Les Paul here and there somewhere in the middle where the band drops out and then this melodic line comes in after a minute or so. I used a Les Paul on that for nice thick, huge sustain.

IC: Tone-wise, this album has a similar vibe to previous releases, although many of the leads seem rounder and juicier, yet without sounding more distorted. Is there anything you did differently in terms of micing or EQ?

GB: Not necessarily micing-wise or EQ-wise, but I’m feeling way more confident with my production skills overall. So what you’re hearing might be due to how open the album sounds. I really wanted to leave it open, and have a lot of room for each instrument to breathe.

I’ve been known to have, like on my first album, all of these different instruments. With Turn Of The Millennium I went down to Prairie Sun Studios to do this album for Mike Varney at Shrapnel Records. We get there and Larry Brewer just finished mixing Soundgarden’s album – what did that band consist of? I think it was bass, drums, guitar and vocals – a pretty simple but cool layout. So we pull up my tracks, and we’ve got flutes, oboes and all of these different instruments and Larry Brewer just looks over to me like I’m nuts, and he’s like: ‘Man, I’ll just be happy to get through this thing.’ So the mixes were quite dense. Unfortunately, on that the production was nowhere near, not even in the ballpark of what I wanted it to be.

So ever since then I’ve been really striving for better and better production. Throughout the whole album I mixed up the amps a bit using the JCM 800 that I mentioned, and an old 1976 Mark II. I just recently acquired another nice ’77 JMP, but I also used some JCM 900s and an assortment of guitars. This is the first album that I’ve used the JCM 800 for lead sounds. A lot of people attribute my sounds to a Strat, the TS9 Tube Screamer and the JCM 900 amp. And it’s funny, a lot of people really diss those 900s, but I love all kinds of Marshalls. The 900s, for me, give you a real cool smooth, liquidy overdriven sound.

I really like to hear every single note in my articulations. Tone is like a chick. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder – some people may love the tone, some people may hate it, but hey, it’s art. To each their own. But for the most part the amps I used were the same. But the JCM 800 I used quite extensively on this album, and that is also what you might be hearing that’s a little bit different.

IC: The bass tones have definitely moved up a level on this record. Can you tell us a little bit about your bass rig?

GB: Yeah, the bass was a lot of fun. I have always really, really enjoyed playing bass. To me, it’s not just the secondary instrument. It’s not like: ‘Okay, it’s time to lay the bass track. Let’s hurry up and get through this thing.’ I really, really enjoy it a lot – it’s guitar, man! When I was first starting out on guitar, I got this cheap little SG-style bass, and ever since then I’ve really loved playing bass.

On this album, I really wanted to bring it up a notch with the bass. I used an SVT Classic head made by Ampeg, and also an Ampeg cabinet. I used a couple of different basses, one that I’ve had for a while, the Fender Precision and this other bass that I just recently got a year or so before this album – a Music Man Stingray bass. I miced up the Ampeg cabinet with a [Sennheiser] MD421 mic, and I also went direct, and I just used a combination of direct and the mic when mixing.

I also had this custom cabinet made. A lot of guitar players that live in apartments might be familiar with these little isolation boxes. This is not an isolation box that you may think of one to be, but what it is is just this box that surrounds the microphone. I used it for the bass recording. It just goes right in front of the microphone. It’s pretty big – I’m guessing it’s 2 feet by 1½ feet.

The idea is that it minimizes the room reflections, so it really zooms in to what you’re hearing out of the speaker and not so much the room. And just by backing off the iso box a little bit, you can fine tune it to have as much room sound as you want. So that was pretty cool. I was really happy with the tone. It was really a combination of things: that iso box, the cool SVT classic amp – that amp just kicks ass, man – and the Music Man Stingray bass.

IC: I also noticed that the overall dynamic range of the album doesn’t sound too compressed. Was that a conscious decision?

GB: Extremely conscious decision. When I mix and master these albums, I get reference CDs from artists that I’ve enjoyed listening to throughout the years, and lately, since the mid 90’s maybe, these great artists don’t mix with dynamic range in mind. It’s like a lightbulb – you put it on and it’s the same volume throughout, with basically no dynamic range.

I’m really opposed to that. I like my music to breathe, to have distinctive soft points and loud points. It doesn’t necessarily have to be in your face. I guess people put music in their cars, or are working out with their iPod or whatever they’re doing. Having albums totally compressed like that may minimize fluctuations in the volume due to outside noises or whatever.

But anyway, for this album I wanted it to be very musical and dynamic, so I used a minimum amount of compression while mixing, and a very limited amount again when mastering. So it’s pretty dynamic – it’s got a good -12, -14 dB dynamic range, where the max that I hit was a good maybe 12 dB dynamic range in that room.

IC: What are some of the reference CDs that you like to use?

GB: One that I always go back to listen to and use is old Rush from the 70’s and early 80’s. Not necessarily for the songs, though I was a huge Rush fan, but for the pure fact of hearing how the album was mixed and mastered. They just sound so open – the cymbals are really up there.

A lot of bands today, I listen to them and I can’t even hear the cymbals – they’re so way in the back. It’s all a compromise. Mixing is the art of compromise, it really is. But with a lot of bands, I think: ‘Wow! I can’t hear the cymbals. Phenomenal drummer – I wish I could hear the cymbal work more.’ Back in those days, you could really hear the cymbal work. Rush is always one – I throw on Tom Sawyer, for example, just to hear that great dynamic range and the production of that album.

I’m hesitant to name any bands that I dislike the production of, but there are far too many of them out today. I think: ‘Man, those are some great musicians and bands, but the production – they just squash the hell out of the mix.’ So I’ll leave it with early Rush as a prime example for me, for when I’m starting to mix and master.

IC: One thing I’m curious about and impressed by is the sheer amount of music that you’re able to put out on such a regular basis, particularly in the last couple of years. Can you talk about your workflow and how you’ve established it?

GB: I’ve always written a whole lot, but there was a period in the early 2000’s before Venomous Fingers and a little bit after where I wasn’t putting out as much music, though I was still writing. After Venomous Fingers I was looking for a singer, and working on this album Flying Through Infinity along with Planetary Alignment. So I wrote a lot of music, just as I always do, but my main focus was the production on that album.

Sometimes it’s difficult to get all of the musicians to record within the time frame that you’d like them to, you know? That was quite a challenge on that. But the past few years have been great. Like I mentioned earlier, I already completed another album this past December. It’s partially recorded. I’ve got the foundation all recorded – the whole thing is there. Every single note that’ll be there has been written, and I’m gonna be recording that throughout the summer. Marco Minnemann will be doing the drum tracks. I’ve already started writing another album that’s going to be released probably in 2011.

With the workflow, I tend to get into these intense writing phases at least a couple of times a year. I write throughout the whole year, but there’s always a couple points within the year where I pop out an album. It takes me about two to three weeks to write an album, and that is total focus, man. I’ll wake up, and I have a minimal amount of students that I teach – a lot of time is focused on writing and recording and playing and that stuff.

But even when I’m teaching, I have ideas just pouring out of me. I’ll be in between lessons – I have my studio downstairs and I’ll run upstairs in between lessons and write an idea down that I thought of. It gets pretty intense, man. It’s just a two to three week intense focus period of this inspiration. I have no idea where it comes from, but it’s there.

But even when I’m teaching, I have ideas just pouring out of me. I’ll be in between lessons – I have my studio downstairs and I’ll run upstairs in between lessons and write an idea down that I thought of. It gets pretty intense, man. It’s just a two to three week intense focus period of this inspiration. I have no idea where it comes from, but it’s there.

I still use pencil and paper quite often, even since the advent of the computer and these music programs, of which I use Logic for most all composing and production. A lot of times, like on Turn Of The Millennium, I used primarily paper and pencil. Like ‘Ripped To Shreds’ – I wrote that in my girlfriend’s convertible on the way from Chicago to Florida. I get down to Florida and I have these eight to ten pages of music, and I’m like ‘Holy crap! What did I do?’

So I write this stuff down on pencil and paper a lot of times, in combination with the score editor and Logic, and after all of the parts are composed, then I’ll start recording the guitar, the drums, and the real bass and stuff.

There are times, like when I did the Mogg/Way album Edge of the World with the UFO guys [Phil Mogg, vocals and Pete Way, bass] – when I wrote that music, I pretty much picked up a guitar and freeform jammed to create some riffs and whatnot, but typically I don’t write thinking of riffs. It’s all leads, progressions, cool modulatory devices, ‘How is this augmented sixth chord going to help me modulate to this other key that’s a half step higher than where I’m at?’ – all of these really neat things that excite me.

There’s usually three to four different approaches I take to writing. One is: I’ll start with rhythmic ideas, rhythmic motives – I’ll sit there with a piece of paper and a pencil, and just dream up all these different kinds of meters, polymeters and subdivisions. From that, I’ll add chords or melodies. Other times, I’ll begin with a harmonic sequence – a type of chord progression that I like. Other times, it will be a theme, a main melody that I’ll start with and then harmonize it and add the rhythm section to it later. There are different approaches to writing that I use – that’s three of them.

So after it’s all written down on paper, like I said, I start recording. I usually record the guitar and the bass, and then Marco Minnemann will come in and just slaughter the drum tracks – he’s just killer. I’m glad I met up with that guy. But yeah, that’s about it, man. It’s the same writing process that I’ve used since I was very young – just basically paper to pencil, and now with the score editor, sometimes it’s just mouse and score editor. It’s essentially the same thing.

IC: Last time I asked you for advice for aspiring musicians. This time, I’d like to ask for your for advice for people who’ve already committed themselves to a career in music and are looking to take the next step to expand their career. What are your thoughts?

GB: Good question. A lot of people have devoted a lot of time to developing their craft, and they’re looking for that next step to get on MTV tomorrow. I don’t have direct advice for that, but musically speaking – fame, fortune and popularity have never been a concern of mine. What’s always been a concern of mine, is developing my craft as best as I possibly can, and creating with what I learn and explore and develop.

But of course, as an artist, we want to get our music out there – hopefully put a smile on somebody’s face with some of the work that we’ve produced. I urge every musician, no matter how developed they are, to continue exploring new ideas, and not fall into the trap of: ‘Oh, well that sounds weird. I’ve never really heard anybody do that before. Let’s not go there.’ Check it out! Try it – you’d be surprised. Try some of these new ideas that some people may be a little apprehensive of trying.

In this day and age you’ve got the internet – a great resource for getting yourself out there and marketing. But if you spend 30 or 40 hours a week online marketing yourself, that’s great quality time you’re taking away from composing or practicing.

One thing I wanted to direct at guitar players is: let’s get some more focus on composing, too. Who cares how fast this guy or that guy can play? I have no care at all, as far as speed or how slow somebody can play. What’s the quality of music? I don’t care if somebody is playing with their teeth or with their toes – I want to hear some great quality music.

What I’m trying to convey is – at least in your mind, have that music be as good as possible, and explore new ideas and continue learning and developing your skill. As far as trying to get signed to a label or do it yourself – like I said, you’ve got the internet, and you’ve just got to ask yourself: ‘do I take the artistic stance or do I take the business stance?’

The first one being: ‘I’m going to spend a lot of time composing and working on my material’ – for those types of people, it seems that the record label route would be the better route. That way the label can handle the marketing and all that comes along with putting out a release.

But if you’re business savvy, and you think you’ve developed your skills to a point where you’re like: ‘Yeah, I’m ready to show the world’ – then the internet is a great resource. If you’re willing to spend time a good amount of time on the internet networking… There’s all kinds of these social networking sites that we’re all aware of, that you can get music onto. But if you’re going to do it yourself, be prepared to spend an ample amount of time marketing yourself.

For me – a lot of people say: ‘George, why don’t you put out the releases yourself now? A lot of guitar players have heard of you at this point, so why do you feel that you need the record label?’ That’s a good question, but again, I really like spending a lot of time on writing and recording. I really feel, Ivan, that until the day I take my long dirt nap, that I’ll always be able to improve my skills. I don’t mean just on the fretboard, man, but as far as writing and trying new ideas and really gaining more maturity in my writing.

IC: You mentioned that you’ve already composed quite a bit of new material – what can we expect from you in the near future?

GB: For this album, I recently acquired this Hawaiian ukulele and a washboard. I used that, and I’ve got a kazoo. I used that, and I’m doing some really cool polkas. So I’ve got this banjo, ukulele and a washboard I’m redoing some polkas, and it should be pretty cool [laughs]. There’s a lot of great banjo players out there – no offense to them, but I am not one of them.

Seriously, though, man – these things that I’m working on… I don’t want to reveal too much right now, but I will say this: they’re highly immersed in Romanticism. They’re tonal, meaning they’re not super far out of left field like Planetary Alignment – which I’m happy with, but it’s very atonal along with Step Into The Future.

Lately I’ve really, really been exploring different types of form. In particular the sonata allegro form, that’s a lot of fun, and also the rondo form. I think a lot of people get trapped in the whole thing of: ‘Okay, we’ve gotta have an intro, a verse, a chorus. Let’s do a little solo and ride out on the chorus.’ It’s a simple song structure, but there’s a lot of others – like the rondo.

But again, these new releases are heavily immersed into the Romantic era. I love that era – Franz Liszt, Frédéric Chopin, Brahms, Gustav Mahler – man! Holy cow! I wish there were more hours in the day for listening. A lot of my time is spent on either studying or writing and recording, but when I do listen, I love listening to that stuff. Not only the Romantic era, but on The Dawn Of Time there’s some nifty counterpoint in there that is very Baroque-ish, and there are some Romantic-style melodic concepts and harmonic concepts, too – but not as elaborate as these upcoming releases that I’m working on now. So I’ll leave it at that. No washboards, no banjos and no ukuleles – I promise [laughs].