Dave Martone hails from Vancouver, British Columbia (Canada), though he’s originally from outer space, where he devised his unique brand of modern progressive fusion. His style combines tasteful, jazz-inspired phrasing with fierce riffing and high-octane techniques – always highlighted by his fresh approach to modern production. Be sure to check out Dave’s exclusive Guitar Messenger Masterclass lesson.

Dave Martone hails from Vancouver, British Columbia (Canada), though he’s originally from outer space, where he devised his unique brand of modern progressive fusion. His style combines tasteful, jazz-inspired phrasing with fierce riffing and high-octane techniques – always highlighted by his fresh approach to modern production. Be sure to check out Dave’s exclusive Guitar Messenger Masterclass lesson.

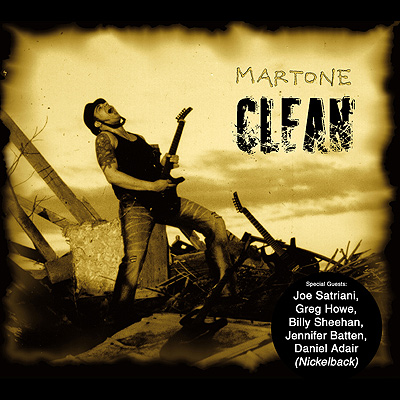

Since arriving on Earth, he’s delivered numerous studio albums of his own, as well as several collaborations with various accomplished earthlings. On his latest release, appropriately titled Clean, Martone strips down his complex sound in favor of a more straightforward rock approach, emphasizing strong melodies and catchy grooves. The album features guest appearances by players such as Joe Satriani, Billy Sheehan, and Greg Howe.

I had the opportunity to sit down and speak with Dave during the 2009 NAMM Convention in Anaheim, California:

IC: Here we are at NAMM 2009. What’s going on – what’s a typical day like for you out here?

DM: I just finished the third day here, so a typical day would be… Well, I’ll tell you what happened first off: I got off the plane and was rushed to Hollywood, and did a show at GIT. That’s a cool place for musical education, MI [Musician’s Institute]. They have all kinds – like KIT for keyboard, VIT, etc. I did a show with a guy named Dave Weiner from the Steve Vai band, and another guy named Rob Balducci – great players. So we did like a mini G3, which was cool. We did that, and then came into Anaheim Friday, and then I played three shows. The first one was for Digitech processing, cool stuff. They make the coolest pedal in the world – do you know which one that is?

IC: The Whammy!

DM: It’s the Whammy!

IC: The one and only.

DM: It’s the red pedal. I don’t have it right here, but I have it – it’s over there. [points to his off screen bag] But it’s just the coolest pedal in the world.

IC: And you take advantage of it!

| [flashvideo file=”https://guitarmessenger.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/playlist1.xml” width=412 height=357 playlist=bottom playlistsize=105 /] |

| Click play above to watch the video of this interview. |

DM: Totally! And I step on as many as I can, and screw up as many as I can. I think I’ve gone through probably around eight, because I beat the crap out of them. And then after that I did a show for Parker Guitars. And then after that I did another show for Vox amplifiers. That was cool, because at the Vox amplifier one, that was a bigger stage they had for Vox, Marshall, Korg. And it was cool. On the sign, where they have everybody playing, it said: Billy Sheehan – 1 o’ clock, Carl Verheyen 2 o’ clock, Yngwie Malmsteen – 3 o’ clock, Dave Martone – 5:30. I’m like: ‘Whoa!’

IC: You’re in good company.

DM: I was in good company, and seeing that, I actually took a picture of the sign and fingered my name like this, [points] and I’m like: ‘There it is.’ It was cool.

So, a standard day is: I like to sleep in a bit, and pretty much get up. I practice just a little bit to keep the fingers warm, but then it’s just pretty much playing all day at the shows. And it’s kind of difficult, because you don’t have a lot of time to get shit set up.

IC: Plug and go.

DM: It’s not like: ‘Oh, the luxury of soundcheck.’ It’s just plug and go and hope for the best. It’s in-the-trenches type playing, but it’s cool, it’s a lot of fun, and it’s a cool thing, because you get to see a lot of your buddies. It’s a cool thing to see my buddies that are out there, and vice versa, me watching them play. And then evening times – unfortunately I’m not playing any evening shows at this point, but I’m gonna check out Paul Gilbert tonight, and that’s gonna be cool.

IC: That’ll be cool for sure. So, the new record, Clean, came out not long ago. Tell us about this record. How did it come together, and what was the writing process like for it?

DM: I love this record. I love them all, but this one in particular, because it, I think, is more real – not that the other ones were fake.

IC: In what sense?

DM: It’s truer to who I am, I think. A lot of times people get caught too much up in picking as fast as they can, or sweeping as fast as they can, or tapping as fast as they can, and they lose the focus of the tune – that kind of disappears. So the focus of this was the focus of the tunes, and basically, all killer, no filler. That was the goal. The reason I wanted to get it done quick, too, was I had a couple of really special guest artists waiting to participate, and I knew that it was time, so I wanted to make sure that I could get it moving forward.

The album was done very quickly. It took a long time to negotiate the right record contract. We were talking to Favored Nations, Steve’s label, my old label Lion Music, and Magna Carta, which is also a subsidiary of Shrapnel. So I was talking to Mike Varney, cool dude – I actually was talking to Steve Vai, as well, only through email. We were just trying to work out the best deal between all the different companies, and… Magna Carta offered the most potato chips, and I like dill pickles, so they gave me lots of those – not lots, but enough.

The record is basically about good tunes, memorable tunes. It makes you do this, [headbangs] and that kind of thing. I lost all the progressiveness, I’m not really into: ‘1-2,1-2-3-4-5, 1-2-3-4-5-6 and a half, 1-2-3-4’ all that crap. I wanted to feel the… [headbangs] that thing. And, don’t get me wrong, there’s some parts where I’m playing my… trying to play my ass off. But most of it is strong melodies, I think. That’s the focus of the disc.

IC: Yeah, in particular I noticed that on the bossa-inspired track on the new record.

DM: ‘Bossa Dorado?’

IC: ‘Bossa Dorado,’ yeah. There’s a very cool melody in that one. What inspired that?

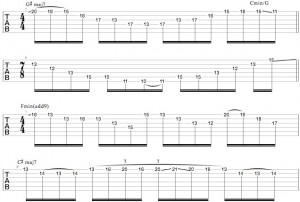

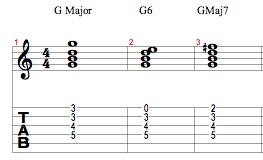

DM: That’s like a gypsy jazz type of melodic form… simple progressions like, [plays progression] and then, [plays second section of progression] to be able to use some of the harmonic minor stuff. I always have a love of the flamenco music, as well. I play in a flamenco group back home called Kadabra.

IC: Oh, cool. I didn’t know that.

DM: Yeah, it’s a very cool flamenco group. It’s in many different permutations. It can become just me solo, two guitar players – another guy named Brian Poulsen, really good guitar player, and then the addition of either by upright bass by David Spidel, who also plays with me in the Martone band, and then a percussionist named Mike Michalkow. And that’s a lot of fun, man, because it’s virtuosic, but you have the groove there. It makes people alive, drinking sangria, having fun, women are taking their clothes off, things are happening… well maybe not that. Yeah, so it was a clever way to disguise virtuosic playing inside of really rhythmic music. And that kind of inspired that tune as well – Bossa Dorado.

IC: How did you get into the flamenco style? I know that a lot of rock-based guys might get through the harmonic minor thing by the Yngwie route and that sort of thing. So how did you get into it?

DM: I got into from when I was growing up at home. My father had a bunch of flamenco records, and he took me to my first flamenco teacher. The first flamenco record I heard was a guy named Carlos Montoya. Amazing! On a flamenco guitar he would be like, [plays legato runs] all like this sick legato stuff, all over the place! I can’t imagine – if I shook his hand, it would be like, [imitates a crushing handshake] my hand would be a smoking pulp. Because the strength to be able to do that was crazy! There was another disc my father had; it was called Las Indias Trabajadas, two Indians’ sounds.

Then he took me to a classical/flamenco teacher, so that was the first I heard of it. I didn’t learn any of the techniques, really, it was just the sound. I really don’t know what I’m doing today on it – it’s just the sound that I try and emulate. I hear it and try to emulate with the hands. If some purist would see me, he would say: ‘You’re a fricking retard. You don’t know what the hell you’re doing.’ And I’d say: ‘You’re right! I don’t. I have no idea.’ But I’m relating the sound the best I can.

IC: Going back to Clean – the tunes are always solid, there’s not much filler. Each tune stands on its own on the album. But one thing I really dig is the production on all of them. In the instrumental rock guitar genre, that’s one of the things that often falls behind, and you seem to have a really good grip on that. I understand you do a lot of that yourself, or even all of it. Is that right?

DM: I do. I love that equally the same amount as playing, and it wasn’t always that way. But I remember being really young with my father, when we would clean up the back in springtime, we would go to the dump. I would look for old TVs and radios, and rip out the speakers and try and hook them up to my shitty guitar amps. I was always interested in that part of it, too. So, I went and I got a degree in recording engineering and production in London, Ontario. They showed me the ropes.

I suggest to a lot of people, if you’re checking this out, that it’s very beneficial you take some courses like that. Because today we, or us, or you – are needing to be able to record yourself. A lot of people go: ‘Yeah, I know what I’m doing. I can push record.’ True enough, you can, but there’s a lot of nuances to make it sound, as you were saying, P-R-O, meaning pro. So, the hardest thing is the drums, to get those. Because when you’re recording, and probably people who have tried this at home, if you get a shitty drum sound, it just sounds so demo. Sooo demo. So lo-fi, so crappy. And it’s the hardest thing to get the best sound on the drums. Everything else also takes a lot of work, but I just take a lot of pride in taking time into that.

I know a couple of really great engineers in Canada: one guy’s name is Mike Fraser. He’s done a lot of Satriani records, Yngwie records, Strapping Young Lad records. He’s up the avenue of heavy sounds, killer drums and stuff – so I can email him when I want. He usually gives me some bullshit answer, like: ‘Just stick the mic wherever!’ But he gives me some ideas, and lets me know that it’s not a science – have fun with it, too. I do have a studio at home, it’s called Brainworks, and that’s where I recorded and mixed all the records. Thank you for the compliment on that. I make sure everything’s punchy, powerful and clean.

On this record, I tried to use the least amount of direct signals – meaning direct guitar sounds, or triggers on the drums. I wanted it to be very real. That helps with the depth of the sound, and the punchiness of the sound, if you know what you’re doing. It’s all real! For instance, the album before this, When The Aliens Come, was totally different. There’s a lot of direct, lots of loops, and production and ‘blip-blop-bloop’ sounds and all that stuff, so it was a totally different idea. I love them both, but I’m in this vibe.

IC: Is that what inspired the album name [Clean]?

DM: Yes. There were a few things. It was the hardest thing in the world to name this freaking album, because I was constantly going back and forth with Daniel Adair, the drummer. I would be saying names like: ‘Egypt’ and he goes: ‘Sucks!’ ‘What do you think of this?’ ‘Sucks!’ ‘What do you think of this?’ ‘Really sucks!’ So I wanted to incorporate the ideas of having: Number One – the music’s truer, Number Two – very strong melody, Number Three – not as much ego in the music, I mean not all bravado speed playing. I know it’s there, but using it very tastefully and effectively when it needs to be there. Number Four – very strong songs.

And also myself, I went through a lot of personal changes. I had substance abuse – nothing heavy, but smoking cigarettes a long time, stopped all that. I used to drink a lot of booze, beers. You get with your buddies and ‘eyyyy’ – and then it gets out of control sometimes. So cleaning that all up. I was in a relationship that needed to end, so that cleaned up. So with all of that combined, I wanted to summate that into the title of the record. It was hard to think about how to do that. There was a song on the record called ‘Coming Clean’ and I thought: ‘Why don’t I just call it Coming Clean?’ But then I thought: ‘It sounds a little too white, or a little too light, or a little too soft.’ I wanted something that still had some power to it. So someone suggested: ‘Well, why not just Clean?’ So I emailed Daniel and he goes: ‘Yeah! That’s it.’

IC: So that was the hard part. The easier part was the headlines – ‘Get Clean Today!’

DM: ‘Get Clean Today!’ Yeah, I can see that on heroin addict buses or at AA (Alcoholics Anonymous) – or really dirty people who don’t shower.

IC: I also write and record my own music. When you’re doing it yourself, at what point do you know if something’s good enough? When is that snare sound good enough? When is that take acceptable? How far do you push it? Because there are so many details you can deal with.

DM: There are. It’s endless. I’ll tell you what I do: I’ll mix as I’m recording, as it’s going along – not really fine, but I’ll ballpark it in. So I know it’s still not right, but I’ll rough it in. All the parts are getting roughed in. Then I’ll burn mixes down, as I’m working on them, and I’ll put them in my iPod. And I’m advocate of going to the gym everyday, so in the morning, I pop in my iPod, and as I’m working out, I’ll be listening to the music I’m working on. Now at that point I might go: ‘Hmm, ok. Those rhythm guitars need to come down. Ok, that clean part sounded a little out of time in the verse. Ok, the snare was too soft. It needed more beef.’ So I’m listening to this shit as I’m going along…

IC: Writing it down while running on the treadmill?

DM: No, it’s in my head. Then, when I come home, I’ll make the necessary changes and work on continuing on the track. At the end of the day, I’ll do the same thing again: burn the mixdown and put it in the iPod. That keeps going on until, for me, I know every part is fixed. They’re apparent to me because I can hear them. For yourself, you’ll go: ‘Damn! There’s that fricking bass guitar – it sounds a little bit weird there. It sounds too bulbous, or boingy.’ So when you feel happy, that’s when it’s good enough, I would say.

Some people get caught, though. You don’t want to get into that point where you’re always fixing it. They’re always like: ‘This can be better. Oh, now it’s two months later. I could play it better now.’ And then you get in this cog, where you’re never going to put anything out. So you have to watch that doesn’t happen, because that sucks. It’s a cool thing, because every album or piece of song documents you at that time and how you played. And it’s cool to listen back and go: ‘Wow! I played a lot better ten years ago.’

IC: (laughs) Well, hopefully that’s not the case.

DM: Hopefully not.

IC: So tracking back a bit, you mentioned your dad got you some music teachers back home. At what point did you decide to commit your career to music – to go to that recording school, and eventually Berklee College of Music?

DM: It started off from just playing in bands. It all does, right? You’re having fun, you’re playing with your buddies, and then all of a sudden you have a gig. And all of a sudden you get paid 20 bucks and you’re like: ‘Whoa!’ Right? And you’re not thinking about it as for money, I wasn’t – it was fun. It was tons of fun. Then slowly, you realize: ‘I’m making a little bit of money at this.’ So that’s cool. But then you realize: ‘Hmm.’ You get to this point when you’re a teenager, and all teenagers looking at this can relate, because when you’re at 17 your dad goes: [leans in] ‘What are you gonna do with your life?’

IC: I think we’ve all been there.

DM: We’ve all been there. You’re like: ‘How the f*** do I know? I’m 17 years old, what do I know?’

IC: [to audience] If you haven’t been there yet, you’re getting there.

DM: I agree. So, I was faced with that, and I didn’t know what the hell I wanted to do. I knew I liked playing with speakers, like I said, I knew I loved playing the guitar. So I just looked at some pamphlets they had in the high school guidance department or something, and I saw the only music program that was offered was a recording program. So I’m like: ‘Okay! That’s what’s I’m gonna do.’ It’s because it was the only option at that point. I decided to go with that. I applied nowhere else, so if I didn’t get in, who knows. But I applied there and it was the best thing. As I was saying before about the recording, it was an amazing experience. I learned so much there, and from there I got a lot better at playing, a lot better at the recording chops.

IC: How old were you at this point?

IC: How old were you at this point?

DM: I was 17 to 19. I got a lot better at all those facets of it, and that really helped a lot. That’s probably also the point where I practiced the most in my life – somewhere in that point, and a little bit after that, as well.

IC: How much would you say you practiced?

DM: As much as I could, it didn’t matter. It wasn’t documented, but every night there after classes, I would go and eat and then there would be these big lecture halls, like at a university, that you could actually sign out. So I would sign out a 150-seat lecture hall every night for two years, and wheel in all my amps, ghetto blasters, tapes, (Tapes!) and jam all night – probably until two or three in the morning, for two years, from probably after dinner time. Also, being in the there, everybody knew I was in there. So people in the studios who needed something would be like: [knocks] ‘Hey! We need a guitar part!’ ‘Okay!’ And I’d be in and do it. So I ended up playing on a lot of stuff from doing that.

IC: That’s good, to get your experience early on.

DM: Yeah. So that kind of led down the path, and after that I played in a couple of thrash bands in Windsor and Detroit. As unfortunately happens with bands, they all [imitates a windy explosion] and I was stuck at that point around 21 wondering: ‘What am I gonna do?’ I’m looking for another band. And then, I don’t know how Berklee came into my mind – it just did, and so I applied and I got accepted. But I also applied for a scholarship and did not get accepted.

So there was no way I could go to that school. It’s a great school, but it’s just too freaking expensive, for me and my family. But I was destined and determined, so I physically got in my white van and drove to Boston, and I had them set up a meeting with the scholarship committee and said: ‘What do you need to hear to get a scholarship? What is it, tell me?’ They said: ‘We’d like to hear a mixture of classical, some jazz, and maybe some of them combined.’ I drove back home, booked a studio, and wrote two pieces exactly like they said, recorded them well, sent them back in and got approved for a scholarship. [laughs]

IC: There you go.

DM: So the point is, don’t ever take no for an answer. Don’t be an asshole about it either, by pushing too hard. There’s always another way around – there is. Don’t ever take no for an answer, you always can do it. That then led to the path of doing the instrumental albums, starting on that career and that whole idea, and that’s how it all started to be as it comes in today.

IC: That’s a great example of determination paying off.

DM: Yeah, definitely. Because every step of the way, we all make decisions. We don’t know what’s gonna happen down this alley or that alley. We don’t know! I could say: ‘I should’ve moved here, what would’ve happened if I’d moved here?’ but who knows, man? Know why I’m happy? Because I have a guitar in my hands right now, and that’s good enough.

IC: So once you got to Berklee, my guess would have been that you’d major in Music Production & Engineering, but you already got a degree for that back home. So what did you do at Berklee?

DM: I did Performance, and I did a minor in Music Education. The only reason I did a minor in Music Education was because my parents were like: [knocks] ‘What are you doing? What’s a performance degree? What’s that stuff? You should have some Music Education.’ So I did take some of that, and it’s come in handy – I teach for Berklee in the summer times, and I teach for a place called National Guitar Workshop. It’s a good way to keep yourself going around, because there at all of these places are hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of you guys [points to camera] taking classes because they want to get better. That’s a big part of your fan base, too. What better place to be then with people wanting to get better? So it’s a perfect opportunity at that point, and I love sharing stuff to help people get better.

IC: A big part of your playing and your signature sound is the tapping that you do. How did you first get into that?

DM: Eddie Van Halen. Everybody’s heard that, I’m sorry to say that, but it was.

IC: Well, you took it to a whole different dimension. How did you expand upon that?

DM: Thank you. I think it was more of the sound and trying to move across more strings, than staying on one string. A lot of people would stay on one string at that point in time, and then people took it to a whole different level too, using so many fingers with this [left] hand. I can’t do that. I do what I do with pretty much my one finger, or two fingers if I’m doing chords. The sound… I was always very fond of a mono synthesizer sound. I don’t know how to explain that sound, but it’s a monosynth. Go to a store and look for what says monosynth, and it’s got that sound. That’s from the tapping that you’re able to do that. Also, my alternate picking sucks. It’s okay.

IC: You think so?

DM: I do think so. Everyone thinks that they have a problem – I think it’s okay, but it’s a limitation that I’ve always known I had. I work on it a lot, and then I go: ‘Why am I working on this?’ Because I know that it’s not great, so what I’m finding now is: why not let what comes naturally to you be what is you? That’s what I’m coming to grips with right now. Why am I gonna force: ‘I must pick like Al Di Meola! I must!’ if I’m not gonna do that? Al Di Meola already does it. Why not do something that my hands feel great with that sounds like me, and just let that happen? Because it feels flawless, it feels effortless – it feels like nothing. So that’s what I’m focusing on now. So tapping comes into part of that.

IC: I notice that you get a monosynth sound as you mentioned with your tapping, but you also tend to layer many different sounds when you do some of the tapping. For example, some times I hear almost an acoustic sound on top of it. So how do you get that?

DM: That’s very observant of you, man. A few people have commented on that before: ‘What is that? Why does that sound like that? How is that it sounds so articulate, but not distorted, but still smooth? What’s going on there? How is that happening?’ And it’s very easy – the answer is that it’s two guitars playing it at the same time. You know all that stuff. But I’m playing it only once, so what’s happening there is with the guitar, I have the whole electric side playing with distortion, and when I flick a switch down here, if I have a special cable plugged in, it turns on the acoustic guitar.

IC: So it’s got a piezo bridge, and you combine those two together.

DM: Yes, that’s my 6-electric piezo – I combine them together, in the middle position right there, and then I’ll record both of those. So when you hear that, it’s a good mixture. For example, there’s a song off of A Demon’s Dream called ‘Country Maniac,’ and what I did at that point is actually very apparent. If you pan it left and right, you’ll hear one side is the electric, and one side is the acoustic. You can totally hear it at that point in time.

IC: So you actually got to play all those hard licks on electric guitar, which definitely helps.

DM: [laughs] Yes, it does. None of them were on the acoustic. Not at all. Some people might think: ‘How do you play that shit on acoustic guitar?’ It’s not, it’s just on an electric. At other times I’ll combine them straight on as a mono signal, and process them separately and then combine them together – and that’s how the sound happens.

IC: Very cool. And by the way, about the alternate picking – there are bursts here and there that are just…

DM: Yeah, I know…

IC: They’re there! Like off of A Demon’s Dream on ‘Got Da Blues.’

DM: I know, there’s that big one in there.

IC: A couple on the new one, I think actually in ‘Bossa Dorado,’ as well.

DM: Yeah, there’s that one, you’re right. So they’re there. Now that you mention those parts, I listen to them in my head and go: ‘Yeah, they sound cool.’ But… you’re right [laughs] I don’t know hot to explain it. Sometimes they suck but those two sound cool. I’ll give you that.

IC: One thing I noticed in your playing on this album, once again on ‘Bossa Dorado,’ at the end you’re doing some sweeps that remind me of what George Bellas does.

DM: I call it super sweeping.

IC: What does that involve, exactly?

DM: It’s basically just keeping the hand on the chord, whatever the chord happens to be, and muting it heavily and moving across it. Shall I show a little bit?

IC: Yeah, that would be great.

DM: [super sweeps several arpeggios] So it’s not much – it’s just sweeping across and keeping the hand muted heavily. That came from the idea of keeping the hand muted, because a lot of times when people sweep, they’re lifting off of everything. That’s okay, but this gives you a whole different sound. There was a song I did on Guitar On The Edge [a compilation album] a long time at Berklee called ‘It’s About Time,’ and in the end of the song I did a little bit of that stuff. It’s not hard. It’s all in the muting and just keeping the chord down.

IC: Right on. Now, I’d like to ask something a bit different: tell something about yourself that you’ve never mentioned before in an interview. It can be whatever you want – a story, a joke, an experience or anything about yourself.

DM: Hmm. An interesting gig at one point in time – my agent told me I’m doing a solo gig, nylon flamenco, and gave me the address and told me it’s a cool gig. So I go: ‘Okay.’ I go and show up, and I find out that it’s a geriatrics, old old age home. So I’m like: ‘Whoaahh!’ I figured I might just be background while they’re eating, but they had a nice little stage set up for me there with candles and lights, and all of the plush couches lined up for all of these people to watch me play. So I get there, and I plug in and start playing, and it’s funny, because half of them are all asleep in their chair, and there’s a couple going: ‘It’s too loud! It’s too loud!’ and other people are just reading books.

So I finish the first set, and I get off the stage and the organizer comes over and asks: ‘How’s it going?’ ‘It’s cool’ Then a couple of people come up and she introduces me to some of these people who are watching, and she says: ‘Well, what do you think of the music?’ and some old guy goes: ‘I hate it! just hate it! It’s too loud, and it’s horrible. I just hate it!’ I’m like: ‘Thanks, man. I’ll make sure I play a bit louder next time.’ It was an interesting gig, and I just laughed.

IC: It didn’t bring you down too much?

DM: It didn’t bring me down at all. So, there’s lots of those things that happen sometimes. They’re a good memorable point, and it keeps you humble. So this guy thinks I suck – that’s great! I don’t care, and I’ll never see him again. It keeps you humble. So that’s one little piece of information.

IC: You do a bunch of different things in your career – teaching, recording, obviously your whole solo career, and I know you also do some touring work and session work. Out of all of those things, which would you say is the backbone to your career?

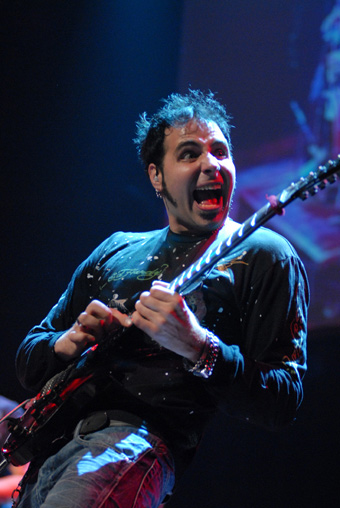

DM: Which one is most important, and which one I want to be most important are two separate things. The one that is the most important, that’s keeping me floating right now, would be clinics and teaching for Berklee and National Guitar Workshop and private teaching and organizing master classes and running different programs like that. What I would want to, and am going to make become the main thing, is touring. I want to be out there so you can go: ‘Oh, Dave’s in Tokyo. Oh, Dave’s in Australia. Oh, Dave’s in Russia. Oh, Dave’s in Tumbleweed, Montana.’

So that’s where I see myself in the future. From there, I’m gonna meet a whole bunch of new people, and I already have from different things that I’ve done. The stage feels so good – I feel like I’m an unleashed animal on stage. I just want to explode so much, and give so much. I love being theatrical, and I love just making all kinds of stupid faces and sweating my face off and just getting so into it. That’s really where I feel like I come alive, and it pushes me to play different things, too – some things I never would play. I couldn’t, because I wouldn’t even know what the hell it would be. When you’re in that zone, I call it the Mojo Zone – sometimes it can suck, and sometimes it just gets awesome. So those, to answer your question, are the different things.

IC: Since we’re talking about touring – you’ve toured with some of these really high-profile bands like 3 Doors Down and, I believe, Nickelback.

Dave Martone and Joe Satriani

DM: [Nickelback] were on the tour, yes. I didn’t play with them, but they were on the same tour.

IC: So one thing that really interests me is that with these high-profile gigs, the idea is that once you get on a gig like that, that is it financially. But then other people say that with some of the high-profile gigs, it’s actually different. So how does it compare, between solo gigs and gigs like that?

DM: High-profile gigs are great because they do pay very well – and of course they do because it’s the pop market. So anything in the pop market is great. You probably start as an average person at maybe $1000 a week – that’s a starting base, some people make a lot more than that or less, but that’s 4 grand a month. It’s average, but you have to remember that when you’re doing that, you’re on stage for 45 minutes. The rest of the day is: [shrugs] ‘What are you doing?’ Practicing, going to the gym, writing music – it’s great.

IC: From your touring experience, do you have the flexibility to do those other kinds of things?

DM: Yes. You can do whatever you want. You can either sit and smoke crack all day, or you can get shit done. It depends on the individual that you are.

IC: So it is possible to do that on tour.

DM: It is. There’s a lot of times that are taken up with press and publicity – you get pulled in a lot of different places. But it’s like anything. You’re at home, you want to practice – you’ll make the time. You’re not gonna sit and watch Seinfeld, two episodes, an hour. You’re gonna not do that. You’re gonna practice… any environment you’re in.

Sometimes it’s more difficult, like you’re in the middle of who-knows-where and you need to go the gym, and it’s 20 miles down the road and it costs 25 bucks to get in there – are you gonna do it? Yeah, because you get back and you feel great. They’re hard to come by, but once you get there, you get to a certain amount of people that you can meet. I don’t think I’m really there yet – I have touches and I’ve done things, but I haven’t had a chance to pop and circulate around in the market like I want to yet, and I feel that’s the next thing that’s around the corner for me.

IC: That’s been working out more and more for you in recent years.

DM: It has been. I’ve been doing a bunch of sessions at home, too, for different major label recording acts, and certain exposure is starting to come now and it’s great. I don’t want to sound egotistical at all, but it’s almost to the point where you’re like: ‘Oh, that’s cool. It’s about time that happened. Okay, that’s cool.’ So, not that I’m not excited about something that happens, like: ‘Oh, I made it into this, or made it into that!’ It’s at the point where you’re like: ‘Phew, okay, that’s happened finally.’ Because it’s something that I knew would happen. It’s a matter of time. Sometimes people are very lucky, and it’s just like: ‘Here you go! Here’s ten million dollars. You can record whatever you want and tour the world!’ Okay, that didn’t happen to me, but it does happen for some lucky people.

IC: As a professional musician, what are some of the biggest challenges you face, both on a playing level and a career level?

DM: You’re always needing to sustain yourself. You’re thinking about the future, which your parents do sometimes: ‘How much do you have in your RSPs? [Retirement Savings Plans] What’s going on with these accounts? Etc.’ So, that’s an important part of it, too, but on the other side of that coin, I’m doing what I love, as well. I’m not doing something that I hate, and that’s a very important thing to be able to have happen for you.

Sometimes in different environments, performing is sometimes not gonna go the best. I’ve had talks with different people, too, and they get really down on themselves after that’s happened. But to be able to pick yourself up and dust yourself off if something goes drastically wrong… sometimes it’s out of your control and you can’t deal with it, but unfortunately shit happens sometimes. So on the other side of the coin, there’s those times when it works out amazing. So try not to get too down on yourself for the bad gigs that show up on YouTube and everybody goes: ‘Whoa! That guy sucks! Look at that! Oh, that’s crap!’ That stuff’s great, perfect. Then people finally go: ‘Wow, I’m glad to see that he’s human.’

The main thing is being able to worry that you can sustain to make a living for yourself or for your family – that’s an important thing. That’s probably the main goal, once it gets going and everything’s moving. Because it’s a very hard industry to keep moving on in, and that’s why a lot of people fall away. They got to a certain age and like: ‘That’s it, man. I’m sick of eating Ramen noodles. I’m sick of having no TV. I’m sick of driving a shitty car with no gas.’ And they’re like: ‘That’s it!’ And rightfully so, man. Who wants to eat Ramen noodles for the whole time?

But then there are the people who say: ‘I don’t give a crap. I love this too much, and I’m gonna keep going.’ And usually, with a driving passion like that, that means they’re going to become very gifted at what they play, and people will start to take notice. It’s inevitable. So I find that if you just keep really on it, hopefully everything will work out for you. That’s the best thing I can say.

IC: What are some of the things that you listen to these days?

DM: Number one is silence, believe it or not.

IC: Oh, I’m sure. Especially after NAMM!

DM: Yeah. [imitates guitar noodling] Even my own playing… Let’s see, the latest thing I’ve been listening to is Enigma, I’ve been listening to some Patrick O’Hearn, bass player – thematic music, I’ve been listening to Gypsy Kings, I’ve been listening to some Peter Gabriel Music, I’ve been listening to the latest Nickelback record, I’ve been listening to some pop stuff like KT Tunstall, and some female vocal music, which is great. Pop music I’m enjoying listening to, because it’s cool. It’s simple, and if you get a good tune, I like it. I’m not worried about all of these crazy solos and stuff, it’s just pop music and it’s simple. That’s some of the stuff I’m listening to right now.

IC: How much of that pop music do you listen to for the production? That’s one of the big advantages that you often get in pop music.

DM: Oh, it is. I listen to a lot of it for sounds, you’re right. Because you want it to sound thick and big, and it’s amazing when you hear stuff, and it’s like: ‘How the hell did they get that sound?’ It’s ridiculous, because the drums are so huge and they’re slamming and they’re being recorded so many times and sampled, it’s just an amazing thing how they get it. So a lot of times when people are coming to me to record music or they want me to produce them, they’ll say: ‘I want to sound like Judas Priest’s Screaming For Vengeance.’ So of course I go listen to that. I’ll listen to it with headphones and see how it’s going, and get the engineering sounds of it right. But most of it, just for enjoyment.

IC: Is there any advice that you can give to young aspiring players out there looking for a professional life in music?

DM: Yes, two words: don’t suck. That’s it. No, that’s part of it, and another one is: don’t be an a-hole. Number three: try and be funny. Have a light attitude, because people want to work with someone that’s fun to hang out with. You don’t want to be someone who‘s like: ‘Oh, I’m so serious and everything is so serious’ and it’s boring. Be able to back your stuff up, meaning being able to have different styles down, so if the band’s like: ‘We want it to sound like Latin.’ ‘Okay, how about this? [slams a chord]’ ‘Yeah, exactly like that!’

Be able to walk the walk, and be able to have some product. People need to be able to hear what you sound like, because if they don’t know what you sound like, how are they gonna know who you are? So if you don’t have a CD, or something on iTunes, or your MySpace page, which you can make really easily, they’re not gonna know. So I would say a combination of all of those things, and then you’ll be sitting here interviewing them. [laughs]