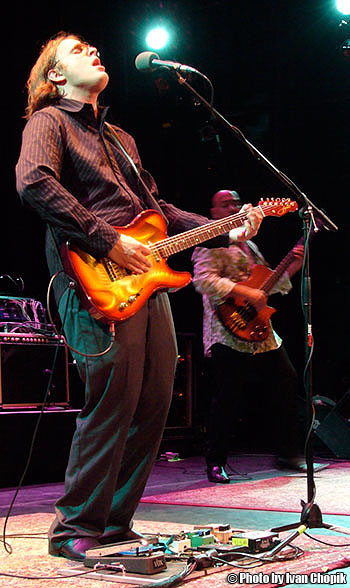

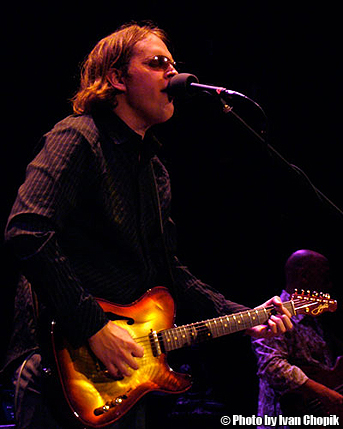

Joe Bonamassa is one of the leading lights in today’s modern blues scene. His latest release, Sloe Gin, debuted at #1 on the Billboard Blues Chart with his previous record, You and Me, still in the Top 10. He was voted Best Blues Guitarist in Guitar Player Magazine’s 2007 Readers’ Choice Awards.

Joe Bonamassa is one of the leading lights in today’s modern blues scene. His latest release, Sloe Gin, debuted at #1 on the Billboard Blues Chart with his previous record, You and Me, still in the Top 10. He was voted Best Blues Guitarist in Guitar Player Magazine’s 2007 Readers’ Choice Awards.

But to strictly label Bonamassa a pure blues player would be misleading at this point. On Sloe Gin, he expands into rock territory and an overall heavier, bigger sound – giving the record a bit of a Led Zeppelin vibe. This is not surprising, considering Joe’s continued collaboration with producer Kevin Shirley, who, in addition to Zeppelin, has also worked with bands such as Rush, Aerosmith, and Dream Theater.

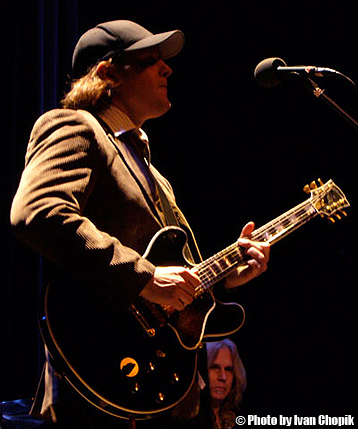

With this in mind, blues fans fear not – Bonamassa’s roots are, as always, firmly planted in the blues, and it can be heard through every note on the record. He is, without a doubt, one of the accomplished blues-rock guitarists of his generation. I had the chance to see it for myself at the Berklee Peformance Center in Boston, MA on October 26th, 2007. To get more info about Joe and his music, check out www.jbonamassa.com.

[flashvideo file=https://guitarmessenger.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/11/playlist.xml width=330 height=75 playlist=bottom playlistsize=55 /]

IC: How is the tour going in support of Sloe Gin, the new album?

JB: We’re doing great here! The record’s still #1 on the Blues charts. We got big crowds, and everybody’s goin’ nuts out here. It’s been good – it’s just been long, you know? We’re on our third month here, and we’ve got three weeks to go – three and a half months is a long tour. I mean, we’re doing five nights a week, six nights a week – it’s crazy. But we’re doing good out here, and I can’t complain. Life is good.

IC: That’s a heavy touring schedule. What keeps you inspired to come out every night and play your heart out?

JB: You just get out there and feel the energy from the crowd at this point in the tour. The first part of the tour is mostly going out, ‘Look what I just did. Look at my new show.’ So you’re inspired to go ‘Wow. Hey, I hope people like it.’ And there’s a little nervous energy… By the time three months rolls around you just go out there and it’s about the crowd. If the crowd has good energy in the room, then you feed off that, and then your show kind of gets elevated.

IC: I understand you like to do some clinics in between the shows. What kind of things do you like to talk about at your clinics?

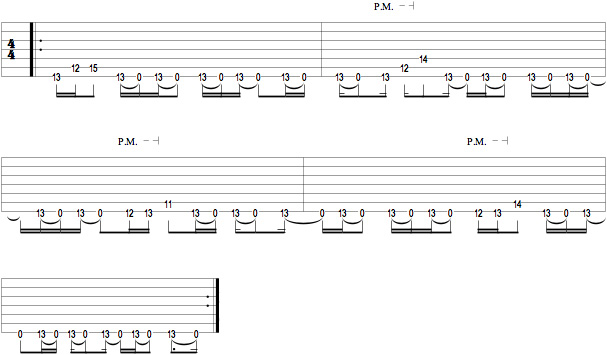

JB: Well, I do some things at schools. At the high schools we don’t really talk a lot about guitar – we kind of talk about the music business in general. It’s kind of career day. I sing a few songs and talk about the blues…. The string of clinics, I talk about certain things that I like. I talk about my concept on guitar sound. I talk about my concept of layering different tones to create one good one. I also talk about how as a blues-based guitar player, you’re basically playing a lot in the pentatonic mode – so I try to show them like these hybrid pentatonic scales that I do. It’s hard to really get to the nitty-gritty with 120 people sitting in the music shop theater-thing that they set up, or at the venue, but I basically do a lot of question-and-answer.

Normally three people come in, they have something they want specifically to know from you. So, you know, it ranges from ‘what kind of wah-wah pedal do you use?’ to ‘when you played on this song seven years ago, what was your mindset when you played your solo?’ And those are the hardest ones to answer, ‘cause it’s like ‘Listen, I don’t know, you know? I don’t remember that fact.’ (laughs)

Joe Bonamassa’s Live Pedalboard

And, the equipment questions…the rig, it seems to get a lot of attention, but it’s very, very simple. I think they’re looking for me to say that there’s some magic box or some secret capacitor in the guitar that makes it sound the same way. A lot of times when we get really into these things, the guy who I don’t believe is satisfied with my answer – that my pedal board could be purchased at any Guitar Center location – says ‘Oh, no, it can’t be true. It must be modified a certain way.’ ‘Fine, why don’t you do this – come up on the stage, take my guitar, play it through the rig – you tell me. And then when you play my rig you’ll sound like you, and when I play through the rig I’ll sound like me. When I play through your rig, I’ll sound like me. When you play it through your rig, you’ll sound like you.’ That’s the thing I learned.

That’s why guitar is so unique. If I went up to a piano and I hit a C note (no vibrato, just a monotone C note), anybody could walk up to that piano and just hit the same C, you know? But when Doc. John plays piano, or when Leon Russell plays the piano, or when Tori Amos plays the piano they phrase it and they interpret it a different way, and it’s the same thing with guitar. I think that’s why guitar and piano are so…there’s so many people into them, because the inflections really make the musician – not the instrument itself, not the gear. That’s what we talk about in the clinics.

IC: Has anyone ever asked you about your cool shades that you wear on stage?

JB: Yeah, they’ve asked me what brand they are. I have four sets of ‘em. I have the very, very hot summer show ones – they’re called Silhouettes, because they basically wrap around your ears. That prevents them from sliding off. Then when you get into the wintertime and the theater’s not cold, and the theater’s not that hot, I wear this set of Pradas and I have a set of Ray Bans, and I have a set of Revos – I think that’s what they call ‘em. Basically, [with] the sunglasses, I’ve put somebody’s kid through college.

IC: It’s interesting – when you talk about venues, you often mention the word ‘theater.’ Is that the kind of venue that you prefer to play in general?

JB: Yeah, we’re lucky enough at this point in time that… the clubs – very difficult. It’s bad sound, bad light, bad power, bad stage, you fall through the stage (laughs). There’s some great clubs and we still play clubs; there’s a cool place we played last night called the Beaumont – rockin’ gig, you know. It keeps us gigging – I like them every once in a while, but I firmly believe that the theater gigs are better for me, because I have a slightly older crowd that prefers to come and have a seat. They bring their coat, they put their coat in their seat, and if they need to get up and use the restroom during the show, or if they get up and want to purchase popcorn, beer or a snack – they have the confidence of saying ‘Well, when I come back, my seat will not be taken by somebody else. I will not have beer spilled on me from behind. And oh, look, my wife and kid can come.’

So we do theaters – there’s a method to the madness. I prefer the sound in the theater, I like the stages in theaters – I just like theaters in general. You know, I actually won’t go to a club to see a band. I go to a theater to see a band. For me, I think it makes for a better experience for the fan. I have a full-service shop here, you know? Not only do I have to make sure the sound is good, I have to make sure our playing is good, I have to make sure that the band is good. I also have to make sure that the experience of the concertgoer, who pays $35, $37, $41, $50 for a ticket, is good.

So we do theaters – there’s a method to the madness. I prefer the sound in the theater, I like the stages in theaters – I just like theaters in general. You know, I actually won’t go to a club to see a band. I go to a theater to see a band. For me, I think it makes for a better experience for the fan. I have a full-service shop here, you know? Not only do I have to make sure the sound is good, I have to make sure our playing is good, I have to make sure that the band is good. I also have to make sure that the experience of the concertgoer, who pays $35, $37, $41, $50 for a ticket, is good.

I want them to walk in and walk out going ‘That was the best concert experience. It was easy for me, there was good energy in the room, yet I didn’t feel like I was gonna have to beat somebody off my wife. To me, when they walk out, I want them to walk out with not one negative thought. Now, it seems like in reality, it’s a lot easier said than done. You have to make sure to dot your ‘i’s and cross your ‘t’s, and know your audience and know what works for your audience, and know what works for you, and try to kind of combine all that.

When we came to Berklee that was one of the better ones in that sense, because it’s like ‘Here we are right in the campus. It’s kind of an expensive ticket on the floor, but we’re doing soft tickets up in the balcony for kids that come from the college.’ And that to me was just perfect, because you get this whole dichotomy of my kind of die-hard fans that come and then some new people that came from the school. I think Fred Taylor did a great job with that.

IC: I’ve noticed your playing differs quite a bit when you play live, as opposed to the tracks that you lay down in the studio. Do you have a certain approach in mind when you go to record in the studio, compared to playing live?

JB: The studio is such a daunting place for me. And some people flourish in that environment – I really don’t. Because I’ll tell you why: the reason why I don’t is, because it becomes a situation where everything is decisions – ‘Is this good enough? Do I like this? Is this solo good enough? Could I play it better tomorrow if I had a different mindset? Is the sound just right? Is there enough reverb on it? Is it too dry? Is it panned correctly?’ Everything’s a fucking decision, and I just get overwhelmed with the decision. We’re just talking about a ten bar solo, or a twelve bar solo. To me, it’s like, live – who cares? We’re going for it – it comes from the top of your head. You just blow it out, and then if I suck tonight – you know what? I’ll be better tomorrow. I’ll learn from my mistakes. The cool thing about live is there’s always tomorrow to redeem yourself.

These little disc things that we make nowadays… they live forever. Unless I want to buy every available copy, at my own personal cost, and burn ‘em, you’re stuck to what you laid down. So the recording process has always been a more daunting, stressful time for me, because I don’t believe I’ve yet to on record just let myself boat freely. And it’s something I’ve gotta get out of my head. I almost play more conservative in the studio than I do live, because I’m afraid of making mistakes in front of the engineer and producer – but that’s who should be there. I should be more fearful of embarrassing myself in front of a thousand people, but I’m not, truthfully. I mean, it’s something I gotta just get my head around.

IC: Speaking of producers, Kevin Shirley was involved with Sloe Gin. Can you explain the involvement and how his vision affected the overall result from what you brought to the table?

JB: His involvement was tantamount to resurrecting my career. He’s probably the most brilliant producer I’ve ever met, and he’s probably one of the most brilliant human beings I’ve ever met. He’s a real nice guy, a super generous man, and he’s also just an A-level musician on all fronts… A musical mind that you don’t see very often – it’s just so rare. I’m just happy, honestly, to be a participant in these last two records that he made for me. It was really his vision. I can really lay the success of Sloe Gin and You & Me squarely on his doorstep. He was just absolutely responsible for that, and it just became a thing – he’s really changed my life, the way I think about music, and the way I think about things in general.

It was a chance meeting that my manager met a friend of his at the gym in South Florida, you know? And without that I don’t think we’d be talking right now – I think my career would be languishing right now. I would not be enjoying this kind of resurgence and all of a sudden going ‘Oh, I know Joe Bonamassa,’ as opposed to three years ago people going ‘Bona-what? I’ve never heard of that bozo.’ You know, it’s like, ‘What kind of name is that?’ That’s what I used to get. So, for me that’s been really critical – and I owe it all to Kevin.

IC: I’m wondering about your involvement as far as the actual sound goes on the new album. I’ve noticed there’s a lot of reverb, as compared to the previous record. Is that something you had in mind or something Kevin thought up?

IC: I’m wondering about your involvement as far as the actual sound goes on the new album. I’ve noticed there’s a lot of reverb, as compared to the previous record. Is that something you had in mind or something Kevin thought up?

JB: I’m a big fan of reverb – I always want more than less. I’m a big fan of those old records, like the Peter Green tone with that big reverb panned to one side. I just think that’s cool. Kevin and I always have to compromise on how much reverb I want… he’d probably prefer a little bit less.

I like it because to me it rounds off the guitar tone. I don’t like guitar sounds that are too dry. Only very few tones – the early ZZ Top tones, that really dry Les Paul – that kind of tone I love, you know? But I don’t like guitar sounds that are really dry, because they get fuzzy in the top end.

The effect kind of rounds off the top end and it kinda takes that 2k fuzz that you’re gonna get out of any amp, that midde-of-the-speaker cone sound… I think the reverb kinda knocks that off a little bit and just kinda gives a nice little sheen around it. It makes it feel stouter on the bottom end, too.

IC: Is the reverb something you add in the studio or is it coming from your rig?

JB: I bring a lot of effects. The delays are all standard-issue Boss DD3. Especially on You & Me I used my spring reverbs a lot, you know? Because I think there’s a difference between the crudeness in those spring reverbs – you know, the old Fender three spring little brown boxes that they made in the sixties – there’s a difference between that and those Lexicon PCM uberdollar devices. It’s almost too clean, it’s almost too clear – it almost sounds too fake. It’s not warm enough.

…The old plate reverbs are great, but no studios have them anymore, because they’re kind of obsolete, because nobody uses them. I love using those over anything. But the Lexicon’s great and sometimes I just use the Fender spring. But to me it’s like you have to meld the reverb and delay together – you reverberate the delay, not vice versa.

IC: I want to talk a little about your influences. It’s easy to lump you in with the same category as Jonny Lang and Kenny Wayne Shepherd because of your age, but you certainly have different influences than those guys. They seem to be more into the American guitar, SRV School of playing, whereas you have different influences. Can you talk about that?

JB: You know, my heroes were the English guys – Paul Kossoff, Peter Green, Eric Clapton. There’s so many – there’s Gary Moore, Rory Gallagher – another Irishman who played the same things, but don’t tell him that. But those guys were my guys – Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page. There’s a certain sophistication to their approach to the blues that I really like, more so than the American blues that I was listening to. BB King’s a big influence – he’s probably my biggest traditional influence. I love Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson and T-Bone Walker and stuff like that, but I couldn’t sit down… I was always forcing myself to listen to whole records by them, where I’d rather listen to Humble Pie do “I’m Ready” than Muddy Waters, you know?

I know that’s the absolute shit to say, but it’s true. It’s just my taste in it. You can’t fault me for it, but some people try. It really does boil down to simply just, I think, the English interpretation of the blues just hit me a lot better, you know? And I know Kenny Wayne feels the exact 180 degree polar opposite, because he and I talked about it. He is like ‘Well, I didn’t like the English blues.’ That’s fair enough. Everything is not for everybody, but to me it was just an organic thing, you know? I also listened to a lot of like Roy Buchanan and a lot of the Boston blues guys like Ronnie Earl and Duke Robillard and Danny Gatton was a huge influence on me – actually my guitar teacher, and stuff like that. And, you know, some of the Texas guys, Billy Gibbons and Eric Johnson – Eric Johnson’s huge for me. I love Eric Johnson. You know, it’s soup to nuts, but it’s loosely based on a lot of the English school.

IC: You mentioned Eric Johnson. I definitely noticed a pretty strong influence of his, particularly in your live playing, more so than in than studio playing. So when did you get in to him, and how did you go about doing that?

JB: Well, me like everybody else in 1986 got that Guitar Player little – I don’t know if you’re old enough to remember this, but Guitar Player used to give you a little floppy disk… It was like: The Greatest Unkown Guitar Player – Eric Johnson with a Strat. ‘Who the hell is this guy?’ So we play it, and it’s like… ‘I’ve never heard a guitar sound like that.’ I mean, it was so far ahead of everybody – he was just beating everybody.

JB: Well, me like everybody else in 1986 got that Guitar Player little – I don’t know if you’re old enough to remember this, but Guitar Player used to give you a little floppy disk… It was like: The Greatest Unkown Guitar Player – Eric Johnson with a Strat. ‘Who the hell is this guy?’ So we play it, and it’s like… ‘I’ve never heard a guitar sound like that.’ I mean, it was so far ahead of everybody – he was just beating everybody.

It was so full, yet it was shreddy, you know, because that was back in the days of the ubershred and so that was like a thing, and I was just blown away. And I had to really work at that, you know? And I throw a little bit of his influence in the live show because I think its fun to do, and I think the crowd really likes it and its like ‘Eh – why not?’ I do less of it on the record because, why would I wanna make… that’s his thing – not mine.

IC: It’s interesting. I’d say his playing is one of the most difficult to imitate – it’s just so different. He’s got a very specific kind of style and you do it very well. So… did you ever learn “Cliffs of Dover” note-for-note?

JB: No, I couldn’t. It’s so hard. You know, I could spend a month doing it, and probably knock it out note-for-note, but I’ve never been one to learn anything note-for-note. And I’ll tell you why, because what happens is that I’d rather learn to do a few of their riffs and then just try to grasp the concept of it all, and then kinda put it together with my own stuff. So it’s like I’d rather just get a few of their riffs and then kinda grasp the concept of why they were playing the riffs in the first place and then just kinda add it to my playing.

I always gotta force myself force myself not to learn anything note-for-note. The only thing I ever learned note-for-note, a long time ago, was a – you remember the movie Crossroads? Not the one with Britney Spears, but the one with [Ralph] Macchio? The guitar duel jam at the end, you know, with Steve Vai and Ralph Macchio, (which is actually played by Ry Cooder), I actually learned that note-for-note and that was difficult and challenging and very frustrating and I’m just not a note-for-note kinda guy, I guess. So I learned a little bit of that and I moved on.

IC: I’m not sure if he’s an influence, because he never gets mentioned in other interviews – but I have a feeling you might be influenced by Paul Gilbert a bit. Can you comment on that?

JB: A little bit. I mean, I like Paul’s playing. I’m not so much into the unabashed shredathon. At least in my later years here, I’ve been more into honestly just going for more of an emotional impact. I really like Paul’s playing… some of the riffs that he plays it’s just insane. But to me, that’s the mentality of striving to be the fastest gun in the west, which I know I’ll never be. So, there’s a couple of concepts I’ve kinda taken from him – his string-skipping thing.

By and large, I would probably choose Eric Johnson, or Shawn Lane, or even Joe Satriani as bigger influences on me, than someone like Paul Gilbert. With that said, it’s not that I don’t like Paul Gilbert’s playing, I mean, it’s absolutely insane what he’s able to accomplish. The guy from Freak Kitchen’s the same way. It’s like, ‘My God, how many notes can you cram into that bar?’ And just when you think there’s no more notes that can be put in there, someone figures out a way to put some more. I mean, it’s insane.

IC: I mentioned that, because I remember a specific incident when you played a show in Boston [October 26, 2007] – you were playing an acoustic solo, and you started out at a nice, comfortable tempo and then you started going faster and someone yelled out ‘faster, faster!’ and you smiled, looked at the crowd – I thought I heard some Paul Gilbert lines at that point, from the “Intense Rock 1” video.

JB: No, you know what is, that “Woke Up Dreaming” moment, that’s my half-assed impersonation of Friday Night In San Francisco by [Al] Di Meola, [Paco] de Lucía – all of them. That’s where I get all that shit from. Really influenced by Al Di Meola more so than anybody else. The way Al was able to pepper his speed within the scale, where he would start off really fast, then slow up in the middle, then go back fast – I just thought that was mind-blowing.

When I first heard that, I was like ‘My God, these guys are un[real]’ and you know? Al was I think 26 when he recorded that. I mean, he was on another planet when he did that thing… That was, to me, a culmination, and that was such a great moment, too. Three different guys, too, – De Lucia had the flamenco thing but it had a different style, and John McLaughlin did his thing, and I just thought Al was the standout on that deal.

IC: I figured it was either Al Di Meola or Paul Gilbert, one of the two. I think Paul was also influenced by Al, so maybe that’s how they’re connected. It’s interesting that as a predominantly blues player, you are very familiar and in touch with those rock and even metal influences. In a fairly traditionalist kind of community, you’re still able to stretch boundaries while still maintaining the strong blues roots and the blues audience.

IC: I figured it was either Al Di Meola or Paul Gilbert, one of the two. I think Paul was also influenced by Al, so maybe that’s how they’re connected. It’s interesting that as a predominantly blues player, you are very familiar and in touch with those rock and even metal influences. In a fairly traditionalist kind of community, you’re still able to stretch boundaries while still maintaining the strong blues roots and the blues audience.

JB: I’ll tell you what – it’s hard, because the traditionalist community doesn’t really believe in their heart of hearts that I am Blues. They think I’m masquerading and trying to hijack the media… at least in some message board discussions about me… In my core, everything I play starts and ends with the blues, and that becomes the real thing. To me, it’s the same way Eric Clapton says ‘Everything I do starts and ends with the blues.’ And I steal the quote from him, because it really is.

To me, it’s about making records that expand your audience, and if you expand your audience, then that’s not a bad thing. If you sell out, then it’s a bad thing. But if you expand your audience while keeping your true fans, that’s a good thing. Why wouldn’t we want cute girls at the shows? That’s self-defeating, you know? To me, if you sing the song with a melody, if you don’t hit ‘em over the head with 8 million notes of guitar playing that only dudes will be into, then…

You have to keep in the back of your mind that you are in the entertainment business and not the blues business, and not the rock business and not the guitar business. You’re in the entertainment business, and your goal as a performer is to entertain as many people as possible. With that said, that’s why I’ve tried to push the boundaries a little bit in my own records – and I don’t say it’s right or wrong for anybody else, I’m just saying it’s what I do, and it seems like people are really enjoying, which is fine.

IC: You mentioned you check out those message boards. Are you in touch with the Internet and all that stuff?

JB: Yeah, I check it out.

IC: In general, how do you think the Internet has affected your specific brand of blues, blues in general, your career – Do you feel its effect?

JB: Hm… I think the message boards helped me, because they get people talkin’ about you. Good or bad, they talk about you – your name. I think YouTube helps me a lot. A lot of college-age kids come to my shows because ‘Hey, I saw you on YouTube!’ I’m like ‘Oh, God. What did you see?’ Some of the recording quality is not the greatest. It’s one of those things where the Internet really helps me – iTunes helps me, MySpace helps me.

People go online for music. They don’t go to the record store and buy a record on a hunch. They go on the computer and they check it out first. Then they maybe buy it, or they just may download it and steal it. I think the Internet and the message boards helped me immensely. I think having people talkin’ about you – and again, with a name like Bonamassa you gotta get people talkin’ about you. It’s not really a recognizable name, at least at first. It’s really important to take any opportunities that you can to get your name out there and get your music out there and expand your audience.

Yeah, I love the Internet and I let ‘em tape the shows. We do a different show, slightly, every night – some good, some bad, some ugly, some great. So let ‘em have the souvenir. Nobody should tell them that they can’t take pictures or record video or tape the show – it’s just part of the game. If a show you did in St. Louis get traded around the country, (and the world right now), and it brings new fans to the shows – awesome. You can’t… You’re kinda cutting your nose off in spite of your face.

IC: You mentioned YouTube. I watched a documentary recently about you on there. It’s a 3-part documentary about you when you were about 16 or so. I’m not sure if you’ve seen it.

IC: You mentioned YouTube. I watched a documentary recently about you on there. It’s a 3-part documentary about you when you were about 16 or so. I’m not sure if you’ve seen it.

JB: I think it was the BBC piece they did when I was a kid.

IC: The Bloodline thing?

JB: Yeah, it was with Bloodline and BB King and stuff like that. Yeah, that was a long time ago. I think I was 15, wearing that crazy-ass plaid golf hat. I looked like a golf prodigy – it was sick.

IC: Your playing was a lot notier than it is now. Is that change something that you’re conscious of, or that you worked on?

JB: I got older. I’m 15 years older than I was back then. When you’re 15 and you have a bit of a skill at it – your mindset, no matter how much you try to tell yourself otherwise – is ‘I wanna impress everybody, I wanna impress everybody, I wanna impress everybody. Everything I know, everything I know.’ You just wanna impress people.

Now at 30, I have a different mindset – I wanna connect emotionally with people. I think that’s the primary difference between Bloodline playing today’s playing – I was concentrating on impressing them with sight and sound before, and know I’m just trying to connect with them on an emotional level. I think if you connect with them on an emotional level it’s a much more endearing, better way to connect with people, too.

IC: As a developing player, is there anything looking back that you would have done differently? Any recommendations to other players growing up?

JB: I probably would have started singing earlier than I did.

IC: When did you start singing?

JB: Probably my biggest regret is that I didn’t start singing ‘till I was 18, but I’ve had such a great, interesting life. There’s tons of stuff where you go back and ‘Well, we should’ve went left. So we didn’t, we went right. It was a bad decision.’ Anything that doesn’t kill you makes you stronger and makes you smarter for the next day, you know?

That’s been my kind of credo on this whole thing. I could have done this, I could have done that, but who knows? Maybe I wouldn’t be sitting here. Maybe if I took the easy payoff then… my career would’ve been over by 18. Or if I did jazz, maybe I would’ve been a huge star like Harry Connick, Jr. Who knows? I’m here now and I don’t regret anything too much to say I think it hurt my career either way. That’s basically the way I look at it. You can’t regret anything – you just move forward and learn from it.

IC: You seem to be quite content and happy about the current tour, you’ve got a number 1 Blues album, and you’ve jammed with some of your biggest heroes. What gives you the blues nowadays?

JB: Like yesterday, I woke up at 6 AM to go on – you know, it’s a great program run by great people, and I’m very appreciative of the opportunity to go on this show – but what gives me the blues is having to consistently get up at 6 AM, go on radio and television, and go out and promote shows and promote the album.

Ivan Chopik with Joe Bonamassa in 2007

It’s part of the game, but it’s hard to get to sleep after gigs before 1 or 2, because you just have this adrenaline and you can sit in your bunk all night long while the bus rolls down the street, and you’re just up. You get 4 hours of sleep and by the time you get done with that and another show you’ve been up for 20 hours, you know? Then you do it again, and you do it again.

What gives me the blues today is trying to take care of myself to the point that I have the energy – that the extracurricular stuff doesn’t beat you down too much to the point where the show suffers. That’s something that’s really been on my mind. I’m very thankful for all the opportunities, but I don’t wanna go on Good Morning Kansas City and suck at the show because I’m too tired and then have to do all the sound-checks and this, that, and the other things that come on every day. That’s the real problem.

Those are Cadillac problems, but in a sense it’s also a concern of mine, because the show is really the most important thing. It’s the reason why we’re here. The fans that paid the money for the ticket, they deserve 100% every night.

Special thanks to Chris Dingman for the transcription of this interview.